Inside Raspberry Pi

An in-depth Digital Foundry interview on the remarkable capabilities of the upcoming $25 credit-card sized computer

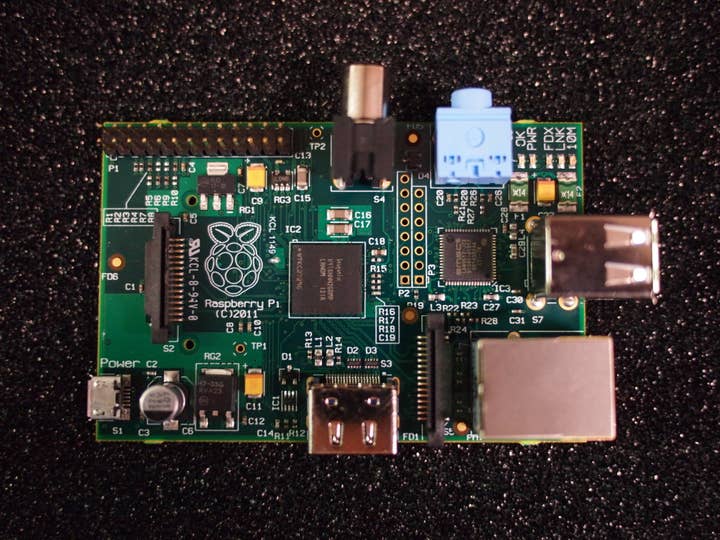

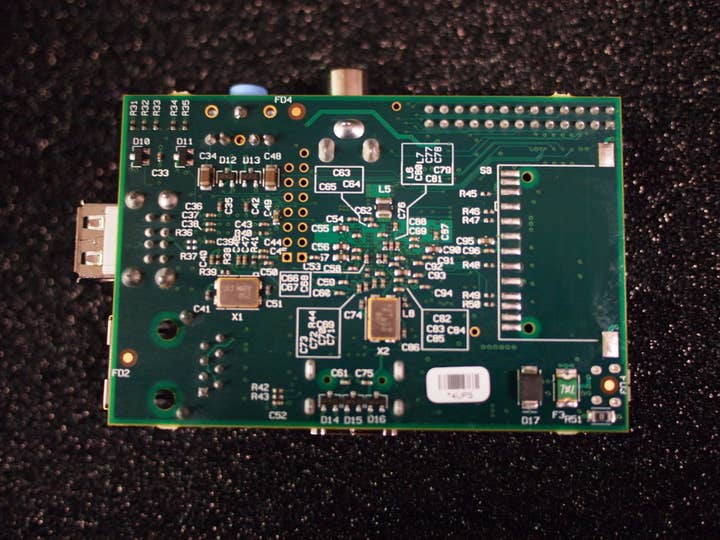

The concept of a $25 computer may well border on the unbelievable, but within weeks the phenomenal Raspberry Pi initiative will finally bear fruit. After years in development, the first production run of 10,000 credit card-sized computers will be available for sale, the aim being to bring an affordable homebrew programming platform to the masses - a modern day successor to the home computers of the 80s, if you will.

In this interview, Raspberry Pi's executive director, Eben Upton, talks to Digital Foundry about the background to the project, the creation of the hardware, its wealth of potential across a number of fields - and what the games business can do to help it succeed.

And being Digital Foundry, we also talk about the device's surprisingly powerful technical specification. Can the $25 Raspberry Pi graphics core double the performance of the A5 chip found inside the £500 iPhone 4S on certain tasks? You read it here first...

Absolutely. You have to remember that when we first came up with the idea, we were just looking at what we could do to improve admissions numbers for the University of Cambridge's Computer Science course. Even when we broadened the scope out to the wider UK education sector, we never anticipated this level of demand, or of press interest.

"The entire developed world seems to be experiencing trouble attracting sufficient numbers of young people into the hard sciences. Certainly educators in North America have been biting our hands off to get hold of Raspberry Pi devices."

That's correct. Right now we have no full-time employees, though I spend about two days a week dealing with various operational issues as the foundation's executive director. Broadcom has been extremely helpful, both in providing our first round of prototype hardware (the alpha boards), and in letting us buy components at a reasonable price in relatively small batches. In addition, several Broadcom employees have spent a lot of their free time over the last six months getting a robust software stack together.

Although PC ownership is at an all-time high, at least in middle-class households, we're still a long way from the situation in the 1980s where programmable home computers were almost ubiquitous among young people; a lot of this market has been eaten by games consoles, which provide little or no facility for programming or other creative activity (Little Big Planet being an honourable exception). Even in families with PCs, anecdotally we know that children aren't always allowed free reign to mess about with the machine; breaking a PC can be an expensive experience. We see the Raspberry Pi as offering a platform with pre-installed programming capabilities, which is cheap enough, and hard enough to break, that kids can be cut loose to experiment.

A range of environments, from Scratch, Logo and Kid's Ruby for younger children and beginners, via tools like YoYo Games' GameMaker, to fully-fledged professional tools like Python and C.

We've talked to Microsoft a little about this. It appears that Windows 8 will require an ARMv7 (Cortex) processor, so our little ARM11 isn't going to cut it. Perhaps a future version might go there; we certainly get a lot of people asking if they can run Windows applications on the device.

I think the developments over the last couple of weeks, including the Secretary of State's speech on IT education policy, suggest that there's been a sea change in Government opinion. We've had discussions with civil servants, but most of the credit here needs to go to people like Ian Livingstone, who have been pushing at this particular issue for a long time.

Again anecdotally, the entire developed world seems to be experiencing trouble attracting sufficient numbers of young people into the hard sciences. Certainly educators in North America have been biting our hands off to get hold of Raspberry Pi devices. What has surprised us is the demand for units in the developing world, both for education and for use as a general-purpose productivity machine.

The key here is cost. Linux has always struggled to achieve a meaningful foothold on the desktop outside the geek community because the Windows tax is simply not that significant a component of the cost of even a $300 desktop machine. Driving down the cost of hardware as we've done helps make the "free as in beer" appeal of Linux much more obvious; it's hard to imagine someone being prepared to pay a $25 OS licensing fee for a $25 PC.

Both devices are solidly profitable at the target price points. This is a real surprise to us; we'd expected to have razor-thin margins and to subsist for our fixed costs on selling higher-margin peripherals. As it turns out, I think we have better gross margins than Dell.

Mostly it's been about doing the boring stuff - good supplier negotiation, and picking out components which are a) available, b) not about to go end-of-life, c) reasonably priced and d) reliable. Securing manufacturing capacity at the right price has been a challenge; this is another place that Broadcom has helped, by giving us access to its Taiwanese sales and marketing team to negotiate off-shore manufacturing locally.