Project M: The Mobile Gold Rush Gets Real

Real gold and a 438% ROI - is Dig That Gold too good to be true?

The concept of the mobile 'gold rush' is a well trodden one, but the connotations of the phrase are wider than the intimation that there's money to be made. Firstly, the old adage about picks and shovels holds true, with Apple and Google the Acme Mine Supplies stores of this particular frontier. Secondly, just like the other headlong charges into metal-rich wildernesses over the years, there are a lot more losers than winners; more swathes of empty ground than lucky-strikes. Big winners dominate the market, with the revenues of the top ten games estimated at up to 50 per cent of the total market take, whilst the bottom 200,000 or so of games take somewhere around just five per cent. There's a comfortable-enough middle market developing, but it's still perceived as a highly risky market, not least by investors.

That doesn't stop companies looking for the next Supercell or King. An increase in mobile-savvy investors means that there's still cash to be found for the right project, but many are still very wary indeed - and not without good reason. I've heard dozens of VCs and Angel investors talk about how vital it is for studios to have proven ARPUs, solid K-factor predictions and established patterns of monetisation before they'll look twice at a project. If who know the market are being so cautious, what hope does a private investor, new to the mobile scene, have of getting a slice of the pie? According to Sean McNicholas, co-founder of Project M, it could all depend on how hard they're willing to work for it.

McNicholas and his team think that with their first game, Dig That Gold, they've built a vehicle for an entirely new form of mobile investment: the franchise model, where investors pay for an individual level in the game and take over the responsibility for marketing it, taking the proceeds, minus Apple's cut and a 20 per cent management fee for Project M. It all sounds alarmingly like a pyramid scheme, and I say so, but the figures which McNicholas is touting for investors are spectacular.

"There are lots of variables involved but we worked out that over a three-year term, based on the historical financial data for a lot of the games in the market at the moment, there's a return of 438 per cent over three years"

"There are lots of variables involved but we worked out that over a three-year term, based on the historical financial data for a lot of the games in the market at the moment, there's a return of 438 per cent over three years," the confident co-founder tells me in the Shoreditch office of the team's marketing unit. "That's been signed off by a chartered accountant."

I'm somewhat taken aback, and I think it shows. McNicholas goes on to explain that, not only has this forecast been given the nod by accountants, games consultant Nick Parker has also given it his blessing. Whilst McNicholas admits that Parker saw the team's predictions of hitting the top ten as ambitious, he also recognised the potential power of the game's two main innovations: the player rewards and the investment model.

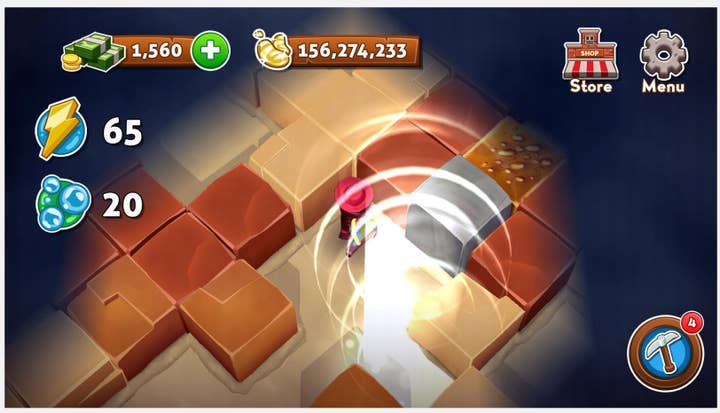

They both make for interesting prospects. Firstly, the game itself has a unique hook. Players navigate isometric mines, chipping away at blocks in search of gold. Air and energy are the exhaustible currencies, which can be topped up either with IAP or by watching video ads. Collect some gold nuggets and manage to leave the mine before your air runs out and the player is taken to a mini-game where they must pan the gold, sifting out the dirt and retaining the nuggets by swiping at the screen. Get rid of all the chaff before the time is up and whatever gold remains is yours to keep - but not just in the game. Project M has a real-world gold trading partner, a company which will convert the virtual gold collected by players into actual, physical gold bars - starting from one gram, but potentially limitless.

It's not virtual cash to be re-injected into the game's eco-system, but actual gold to be extracted. That, says McNicholas, immediately sets them apart from the competition.

"Once you've been awarded your gold bar, you can't go back into the game and spend it. What you do with your gold bar afterwards, is entirely up to you. We just want to be seen as a game that awards gold bars. We're still using conventional routes to market as well. This is not our only marketing push. We've got a meeting after this actually with Albion. Albion launched Candy Crush and so forth. They do part of our strategic marketing. We're using experiential companies, live and house mix experience to do PR stunts. There's going to be a great correlation with the gold itself, so everything that we do is going to be an attachment to people winning these gold bars in competitions, for example. We're going to a PR stunt of a gold prospector say, by Canary Wharf. We're going to show panning for gold and show the similarity between that and the in-game panning. Even with those competitions, with the panning, there will be real gold bars, real gold nuggets in the pan. People have five minutes to see how many gold nuggets they can get. The person that gets the most gold nuggets at the end of the day, will get a real gold bar.

"In our franchise model we've got 200 potential social media pushers out there. It could scale up very, very fast...it's all about getting the right people to work with us, to promote this and take it to a mass audience"

"Our gold provider has got an existing business to produce and distribute gold globally across masses. They've been around for 50 years. They're based in East London, so they're going to work with us to do some promo. They're going to allow some bloggers to come to the bed, do some sort of promo there. We're going to video them testing the game and the person who wins the most gold nuggets in the game within an hour, will be awarded a gold bar. We've got social media campaigns, golden tickets, treasure hunts, lots going on."

Giving your players real gold might be a gimmick, and not one via which anyone could reasonably expect to become a millionaire, but as gimmicks go, it's a bloody good one - especially when the potential is there for a player to swap their time for money by watching ads in return for bullion. McNicholas and team see it as a huge marketing asset - a tangible retort to the perception that players' time is taken for granted, that the fun is the payment they receive for their exposure to advertising. In addition, by giving the investors the responsibility to market their own levels, for which they'll be issued a deep embed code to send players directly to the virtual territory they own, Dig That Gold's potential reach is magnified exponentially.

"The financial data we got couldn't be based upon the typical games companies going into the market using conventional marketing routes," it's explained when I ask about growth. "In our franchise model we've got 200 potential social media pushers out there. It could scale up very, very fast. Even in his report and even when we discussed what we were going do, we had a very low conservative approach to the figures within that business plan.

"When the idea was born for the game, which was about three years ago now, not only were we trying to do something very disruptive to the game market, we wanted to look at how the business model could be developed in the way that we identified as the ones used by the most successful games to go to market, the ones to go viral globally the fastest.

"The funding has been in place from the beginning. A lot of infrastructure. Legal framework, for example, not only for the game to be approved by the likes of Apple, (The team's legal work, which aims to show Apple before going live that Dig That Gold is neither a pyramid scheme, nor an attempt at money laundering, was done by Paul Gardner at Osborne Clark.) but also the legals to do with the franchise model. We've got various opinions from the FCA as to why it's not a collective investment scheme. We've got various opinions from the franchise side to say, this is why it's a franchise and this is why it works. The fund is in place and the development's been done for the game. For us, it's all about getting the right people to work with us, to promote this and take it to a mass audience."

If you are an interested investor, you'll need between £15,000 and £120,000 to take control of a level, although all levels of investment are expected to have the same return (see chart). I ask McNicholas why, if the ROI is so incredible, he hasn't been approaching the major investors, why he needs to go via the franchise route in the first place. Originally, he says, it wasn't for want of trying, but contacting firms like LVP has proven nigh-on impossible. By the time they had built out the franchise proposition, the team felt that the usual cash-sources might not be necessary after all. It's not, however, something that they'll be peddling to OAPs in exchange for their savings - it's going to require research, commitment and knowledge on the behalf of investors. Each investor will have access to a dashboard giving up-to-the-minute feedback on their level's performance and Project M offers a full suite of support services.

"PWC manages all the accounts," says McNicholas when I ask him about the back-end. "They also offer an additional service to the franchisees to manage their accounts as well. The client has the access to a log-in, we've got a sophisticated website. If you're a franchisee, you go to a specific dashboard, you can see real live reports or past stats, financials and so on. You can download any of the training manuals. Video tutorials. How to set up social media. How to create your mind. How to market your business. We have a marketing suite which provides all the content for the logos, the brands, the characters. We also give you social media content that you can post out everyday.

"To get people on board, they have got to have a full understanding of the market, about the business, about their obligations. The franchise agreement is 36 pages long. It's not a two-page document saying, 'I agree to invest in this and this is what we'll give you in return.' It completely lines out the obligations from the Franchiser and the Franchisee. You have a full understanding this is a new market, a new business. People come to us and ask us questions. We present the opportunity. They go and do some due diligence. We present them with the information memorandum and any other supporting documents that they require and then they make a random decision. Then they come to us to say, 'Look. This is something that we're interested in.'

"You've got things like Kickstarter where people pull funds to invest in an app, for example, but you invested your money and you sit on your hands and hopefully it works out or it doesn't. This is for people that want to be part of the gaming community. They haven't got money to set up a dev team and create the next new game. What we're doing, is allowing them to have at their own level within a game platform, so then they can be as creative and push out as much social media as possible and they have a business within a business."

"You've got things like Kickstarter where people pull funds to invest in an app, for example, but you invested your money and you sit on your hands and hopefully it works out or it doesn't. This is for people that want to be part of the gaming community"

As well as the marketing push, investors can choose level layouts and fine tune ads, affecting the need for players to buy in-game resources like dynamite. Control over the level is ongoing, allowing investors to keep fiddling even once players arrive. It's not just for individuals either - with McNicholas suggesting that there's likely to be opportunities for brands to invest at a later date too, theming their levels with logos and ads of their own. If you're a brand with a huge social media reach, with your own ads and a recognised IP or product, the proposition could tie together very nicely indeed.

It's certainly ambitious, and the prospect of a three-year return on a game from an unproven studio (although the dev team has proven chops) is hardly watertight in the current mobile market, but there's a lot of great ingredients here. Find the right partners, get the right ads, hook the right players, and this could be the first example of a new financing model which could change the face of mobile development. If none of the variables come together, though, then Dig That Gold could easily become an interesting sidenote in gaming history - but being interesting is half the battle won already...