2016: Did the "Year of VR" deliver?

Highs and lows of 12 months in a new medium

The following article is part of a series of daily year-end content on GamesIndustry.biz analyzing the most notable news and trends we've observed over the last 12 months

Here we are, in a world I've dreamed of ever since spending £10 and five minutes playing the awful Dactyl Nightmare in London's Trocadero centre 20-odd years ago: I have virtual reality machines in my house. And they're great - they really are. At any time I can pop on a visor and transport myself to the Parthenon, or the deep sea, or space, or a weird football-based gulag. For all the horror, 2016 at least delivered a little VR magic.

And yet...more often than not, when I find myself with spare time to spend on gaming, I don't reach for an HMD, and I don't honestly know why. There are plenty of games I enjoy, albeit not the AAA timesinks which have occupied me recently, and I've largely overcome the creeping realisation that I'm going to look like a bit of a tool when my girlfriend comes home, but still, some of that Dactyl magic has gone. Maybe I've crossed the invisible horizon and have passed into the realm of "too old to be really excited about anything", but I'd hoped to be more enthused about VR at the end of this year.

Maybe it's the inevitable hype comedown. Since January, VR has generated more headlines than any other topic on GamesIndustry.biz. A full spectrum of optimism, cynicism and fairly wild speculation, the stories we've written about the most talked about gaming innovation in years have revealed a medium and ecosystem very much in the throes of its wild adolescence. It's not just been the specialist press, either: nearly every mainstream media outlet has covered the dawn of true consumer VR in one format or another, giving rise to discussions about healthcare, tourism, social interaction, estate agency and product design.

But it's been games which have been the leading format for VR adoption. No VR hardware has tried to market itself without a slant on what it can offer to gamers, and much of the early investment and exposure has gone the way of game developers. Not only that, but nearly every sale of the Vive and Rift, and 100% of the PSVR revenues, can be attributed to those looking for a new way to play. Once more, our industry finds itself at the vanguard of new technology.

The Big Releases

Obviously, the biggest news stories in VR this year have been those hardware releases. Both the Rift and the Vive started shipping consumer units last spring little more than a week apart, and both were soon struggling to meet demand. PSVR came later, in Autumn, and was quickly reporting similar stock shortages. True household VR had arrived, and consumers were apparently lapping it up.

Of course, we all know that there's a pinch of salt to be taken with almost any story of new hardware selling out. Limiting supply and controlling the flow of the retail channel in order to accentuate demand is a marketing ploy which predates the invention of electricity, let alone virtual reality, but nonetheless it was a heartening thing to be able to report on so much early adoption of a technology which still touched on the realms of magic.

Notably, these high-spec sluggers weren't the first to market. Thousands had already had their first experiences of VR in Samsung's Galaxy Gear VR (with which Oculus very wisely partnered for a storefront) and Google's Cardboard - a headset so far along the spectrum from the Rift and Vive that it almost seemed disposable in comparison. Joined by dozens of mobile HMDs from smaller companies over the course of the year, mobile VR saw its next big step forward in November, as Cardboard made way for the Daydream: a slicker, more polished, but still eminently affordable headset from Google.

Almost as an aside, Microsoft also entered the AR fray, comfortably occupying a price bracket and use case scenario all on its own with the Hololens, something which it seems very keen to distance from gaming almost altogether, but hinting at further VR commitments with Scorpio and lining up a list of major industry manufacturers to create low cost VR headsets, presumably for both PC and console.

"We expect VR to be huge, but mass appeal will be lead by VR video consumed through high-end mobile VR devices"

Peter Warman, Newzoo

But as the year draws to a close, it feels as if enough of the major players are on stage for the main event to begin. We can, at least, be confident of who will form the cast of the immediate future of VR hardware, even if we're not entirely sure yet what we're going to be watching.

The Audience

So who is sitting in this exciting theatre of the new? Exactly how many people have bought their tickets, and how are they distributed between the premium and the (relatively) cheap seats?

Well, frustratingly, nobody's telling. New estimates of the current install base of the Vive, Rift and PSVR cross my desk almost daily, but as of yet there have been no official figures for any of the big platforms. One of the more widely supported stories is that PSVR met expectations of being the fastest VR headset out of the gate, selling roughly as many units as the Rift and Vive combined, and that this would put the number of PlayStation headsets in homes somewhere around the 750,000 mark, but that's far from an official figure.

Analysts are certainly cooling their initial fiery expectations on the VR markets revenues and unit sales, or at least pushing the timescale back considerably. SuperData has downgraded its forecasts on market size several times over the course of the year, from a prediction of $5.1bn in January, through $3.6bn in March to $2.9bn just a month later, before calling VR "the biggest loser" in its Black Friday research.

Fellow analysts Newzoo are also calming their ardour on VR games, but see big markets emerging elsewhere, even if consumer tech's biggest player doesn't seem to care.

"We expect VR to be huge, but mass appeal will be lead by VR video consumed through high-end mobile VR devices," said founder and CEO Peter Warman. "Apple is taking a risk by not having a high-end VR solution on the market: the NBA advertises their VR service with images of the Samsung Galaxy Gear. Anyone with an iOS device and an interest in watching NBA games (or other entertainment content) live in VR will be forced to try one of the cheap solutions which deliver an extremely poor experience compared to devices that are optimized for a device such as Samsung's product.

"This can harm the initial adoption of VR as well as the brand image of Apple in addition to the risk of losing mobile phone users to Samsung. Chinese manufacturers Xiaomi and Huawei have recently launched high-end solutions for the China market that has, similar to Japan, a high adoption rate of VR.

"VR games are cool and will entertain the enthusiast, but partially because of a mismatch in business models (pay upfront for entertainment while the whole industry has just moved to games-as-a-service), initial revenues will be limited. There is a natural match in terms of business models between concerts and sports, in combination with the mass appeal, which makes us more interested in the VR video space at the moment. If 10,000 people per NBA game from everywhere across the globe put up $10 to watch a game in VR, it would open up a new revenue stream of over $100M+/year for the NBA."

VR as a business

It's not just analysts who are cooling on VR gaming - some developers are starting to sound less than convinced about the medium's ability to support a healthy ecosystem, with high profile studio owners like Dean Hall recently claiming that "there is no money in" VR, even as they finish up development on a VR title. Luckily, some others are more optimistic. Sam Watts of Make Real says there's not really any difference between VR's growth timeline and that of other platforms, we just need to be patient.

"What makes VR development different from all the other platforms?" he asks. "They've historically shown issues with sustainability, survival beyond the current game, catastrophic boom/bust cycles that see hundreds of developers redundant at a publisher's whim, etc. At this stage, if you are a small team (less than five) with low overheads, then yes you could possibly make it a viable business to continue operations whilst developing the next title, but with such a currently small userbase, who are still finding their feet in regards to what they enjoy and want from VR, it's more like grazing at a buffet rather than sitting down for a set three-course meal.

"So it comes down to risk/reward - do you spend a lot of time effort and money on creating a new genre for VR that wasn't possible before or do you go low risk and follow the current popular vote?"

Sam Watts, Make Real

"This is somewhat reflected in pricing - many tech demo experiences are very cheap or free having already started the indie price race to the bottom seen with non-VR PC and mobile gaming, but without the F2P IAP that traditionally follows. In conjunction with the ongoing lack of understanding and awareness of the amount of effort it takes to make a game, let alone a VR game with a whole new set of design rules to figure out, partially aided by the relative simplicity of creating a 3D scene that works in VR with Unity or Unreal blueprints, VR is being harmed through assumed ease of creation. Yes you can have a successful VR game using Unreal blueprints and throw some stock 3D models of dinosaurs or zombies or whatever into and gamers will enjoy the VR experience but is it really pushing new boundaries that we are told VR offers?

"So it comes down to risk/reward - do you spend a lot of time effort and money on creating a new genre for VR that wasn't possible before or do you go low risk and follow the current popular vote and make an [already] copycat roller coaster, jump scare, zombie shooter, turret defence game? If that gets money in the bank to then invest in something more groundbreaking, then there's nothing wrong with that. But there's the danger that the stores just fill up with lots of similar experiences. But VR game development has the same issues as non-VR game development - people cry out for something fresh and new then reject it when it exists and go back to buy FPS MDK Sportsball Game v1,000 in the millions, whilst complaining that there aren't any original game ideas."

Triangular Pixel's Katie Goode agrees that there's plenty to keep a small team afloat in the space, and that innovation around the strengths of VR will be key to building success and audience.

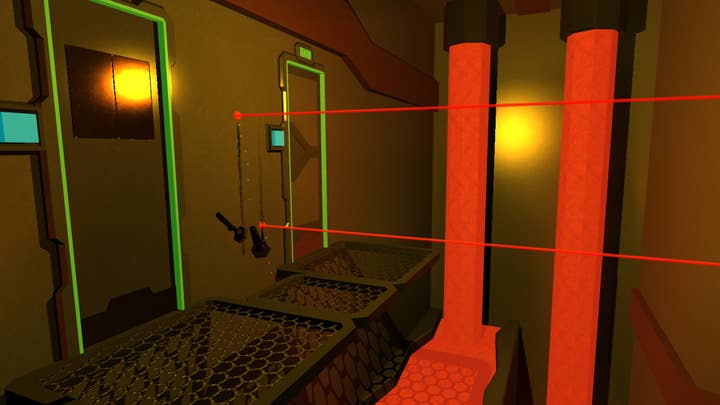

"Early VR has been great for indies - and it's not really about the sales profits," says Goode, who developed the critically acclaimed VR title Unseen Diplomacy. "The opportunity for pubic and business awareness of new indie studios has been the real benefit. For those indies that have got something out early it's kickstarted them having a presence within the industry - which will lead to future opportunities even if future investment ever drops.

"As time goes on, it's going to only get harder for fresh new indies to come and make an impression if the number of games being released increases. The market will get harder to break into - but anything which still breaks the mould will get noticed. Fresh indies will have to keep innovating to stay in the game.

"If you're small enough, VR game development can be a viable business. As long we manage to pay for the basics, we're incredibly happy with where VR is and how we're doing. From our point of view, we feel as though it's still easier for us to make an impression on the public, and much more opportunity to be creative than many other gaming sectors."

"A large majority of third-party developers that have not swapped funding for exclusivity or established work-for-hire deals will not be making a positive return on investment in 2016"

Piers Harding-Rolls, IHS Markit

Piers Harding Rolls at analysts IHS Markit says that we should be neither disheartened nor particularly surprised about the relatively slow ROI of VR investments - but believes the market is building.

"I don't think we should be surprised by the lack of profitability of early VR games and experiences. IHS Markit has always maintained a neutral and realistic view of the adoption of high-end VR headsets and the monetisation of mobile VR. A large majority of third-party developers that have not swapped funding for exclusivity or established work-for-hire deals will not be making a positive return on investment in 2016. This is the same situation for any entirely new platform entering the market with a small installed base and will improve over time. Some developers may have been misled by some fantastical numbers being touted about, which, while building a lot of hype, don't really help games companies to plan how much they should invest."

Are VR developers better off elsewhere?

Speaking anecdotally, many of the fulltime VR developers I speak to are supplementing, if not outright supporting, their games work with projects in other sectors, whether that's one-off projects for large corporations looking to make a brand splash or longer-term consultancy for businesses looking to integrate VR. Some are even moving into these new markets entirely, at least for the time being. So are we in danger of experiencing a brain drain of talent from VR because other industries are dangling a better financial carrot?

"In terms of the directly monetised consumer market, games will be the driving force, but expectations have to be realistic," says Harding-Rolls. "The market will take time to establish itself. Work-for-hire opportunities - whether in games or from other brands in other industries - are probably the most lucrative opportunity for independent VR developers in the current market and a stable form of income. I don't see this as a talent drain, but rather an opportunity for developers to broaden their market opportunity and leverage their skills into new industries.

"VR developers can secure deals with brands from multiple industries but still be using the same skills and development tools, so I don't believe this necessarily means we will see a permanent exodus from the games sector. It's likely that some devs will be forced to look for opportunities elsewhere due to a lack of profitability, but that happens in all sectors of the games market. At the moment VR is not a profit centre for many developers. As the installed bases grow, the content market will scale.

"The demand for interactive content development expertise and the slow rise of VR suggests that game dev skills and expertise will be more in demand. Generally, that will raise the perceived value of existing developers with expertise in VR, so I think that's a positive thing."

Many studios are certainly keen to explore a complimentary business model which pivots VR expertise to the markets who'll pay for it, and Watts believes that we might actually see talent flowing into the industry as a result.

"We run two sides to the business, public and corporate, and they both serve and complement each other very well," Watts explained. "One team works on public-facing VR gaming products that gain the attention of the press, gamers, VR enthusiasts and hardware manufacturers. This feeds prototypes and connections into our R&D team who gain access to the latest and greatest unreleased technology that then feeds into our corporate offerings and next game title, allowing us to constantly be on the edge of developments and first to release (in most cases).

"I think the brain drain actually goes the other way since we only look to work with developers who have experience of 3D simulators, virtual environments and non-public VR hardware that has been available for decades. The threat to a games industry brain drain is the games industry itself in regards to crunch, long hours, lack of professionalism in some studios and developer burnout; this is nothing new or specific to the rising number of VR studios."

So maybe 2016 wasn't so much the year of VR as it was the year of VR getting planning permission. 2017 could be better, but we'll need to manage our expectations and be prepared to broaden our horizons, as both gamers and developers, to keep the Dactyl magic alive.