Core gamers uncomfortable with industry growth - Moore

EA COO says gaming must embrace disruption or risk the same fate as the pre-Napster music industry

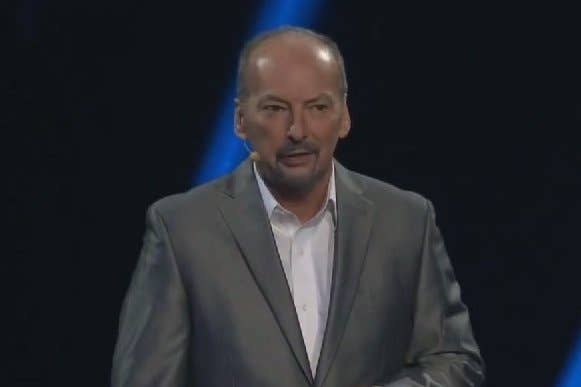

Electronic Arts COO Peter Moore is fairly optimistic about the gaming industry. Speaking with GamesIndustry International this month, Moore painted an upbeat, optimistic picture of the industry's health.

"I think we're going into almost a golden age of gaming, where it doesn't matter where you are, at any time, any place, any price point, any amount of time, there's a game available to you," Moore said. "And our job as a company is to provide those game experiences. And then on our big franchises, tie them all together."

It's a natural extension of EA's games-as-a-service approach, and one Moore has been pushing for years. He wants to offer players unified experiences, like an Ultimate Team mode in EA Sports games with a console component and phone and tablet apps that all tie into the same persistent game ecosystem. However, as the industry broadens beyond the traditional retail gaming model with free-to-play business models, downloadable content, and constantly connected experiences, not everyone can agree on which innovations are ultimately beneficial.

"I think the challenge sometimes is that the growth of gaming... there's a core that doesn't quite feel comfortable with that."

"I think the challenge sometimes is that the growth of gaming... there's a core that doesn't quite feel comfortable with that," Moore said. "Your readers, the industry in particular. I don't get frustrated, but I scratch my head at times and say, 'Look. These are different times.' And different times usually evoke different business models. Different consumers come in. They've got different expectations. And we can either ignore them or embrace them, and at EA, we've chosen to embrace them."

That has resulted in a "primordial soup" of distinct options and business models for people interested in playing games, Moore said. He sees it as a net positive, but ackwnowledges not everyone agrees.

"There is a core--controversial statement coming from me, sadly--that just doesn't like that, because it's different. It's disruptive. It's not the way it used to be. I used to put my disc in the tray or my cartridge in the top, and I'd sit there and play. And all of these young people coming in, or God forbid, these old people coming into gaming!"

The changing makeup of the gaming audience has convinced EA to rethink its development philosophy a bit. When Moore first joined EA, he said the company had 67 core games on consoles and PC that were either in full development, about to be launched, or had just been released. Since then, the company has changed strategy away from the "launch and leave" or "fire and forget" model that used to dominate the industry. With games-as-a-service, Moore said 35 percent of the company's staff is involved in live ops, providing support services or developing extra content for games that have already launched. Now he said the company averages about 11 or 12 games a year.

"It's a completely different approach in the way we're listening to gamers and the way they want to consume games," Moore said.

Since the advent of social media, the entire industry has changed the way it listens to consumers, and that, in turn, has changed the way it responds to them. As an example, Moore said he spent the first night of E3 pouring over Twitter reactions to the EA media briefing, where it showed off very early looks at its new Star Wars, Mirror's Edge, and Mass Effect games, as well as glimpses of untitled Bioware and Criterion projects.

"You have to embrace social media as a plus rather than a negative. Everybody has a megaphone now. Everybody has an opinion, and you learn to filter the rant from the constructive feedback."

"Half the people loved the fact that we were showing well into the future," Moore said. "And then the other 50 percent were basically calling BS because it was conceptual prototypes (which is how we build games, by the way). So you're kind of damned if you do and damned if you don't. Our view was we wanted to get early feedback on where we were. And when we say early, we mean years in advance. Publishers typically, and we were no different in the old days, just don't like to do that. You just don't like to expose yourself and open the kimono to gamers to get that amount of feedback."

As uncomfortable as that might be for some, Moore said EA is determined to have the community involved in the company's business going forward.

"You have to embrace social media as a plus rather than a negative," Moore said. "Everybody has a megaphone now. Everybody has an opinion, and you learn to filter the rant from the constructive feedback."

For example, Moore credited fan feedback with the decision to give the Need for Speed franchise a break in 2014 after more than a dozen years as an annualized franchise.

"We were hearing a lot from the Need for Speed community saying, 'Wouldn't it be cool if? Couldn't we do that?' And you just know that you can't get that done [on a 12-month release schedule]. When we say 12 months, it's really 10 months of actual work. So you just make the decision that is better for gamers."

The hope is that decision will also be the better choice for developer Ghost Games, which took over the series with last year's Need for Speed Rivals.

"We as an industry have to embrace change. We can't be music. We cannot be music."

"They have adopted a franchise that was inextricably intertwined with Criterion for years," Moore said. "And they need the time to make it their own, and they deserve the time to do that. My job is to make sure we figure out something else that would go fill that revenue gap."

Moore said all of these innovations are working to broaden the audience of gamers, and that's seen as unappealingly disruptive to a core audience who liked the industry just the way it was. But as threatened as that crowd might feel, Moore sees a greater threat in not changing at all.

"We just have to embrace it," Moore said. "We as an industry have to embrace change. We can't be music. We cannot be music. Because music said, 'Screw you. You're going to buy a CD for $16.99, and we're going to put 14 songs on there, two of which you care about, but you're going to buy our CD.' Then Shawn Fanning writes a line of code or two, Napster happens, and the consumers take control."

After that, the industry floundered until Apple introduced iTunes and a more consumer-friendly way of acquiring music than recording companies had historically allowed. But even then, Moore said, the damage was already done.

"Creating music to sell is no longer a profitable concern. The business model has changed to concerts, corporate concerts, merchandise, things of that nature," Moore said. "Actually selling music is not a way of making money any more, except for a core group."

"I get grumpy about some things, but if the river of progress is flowing and I'm trying to paddle my canoe in the opposite direction, then eventually I'm just going to lose out."

Moore said he understands a lot of the misgivings people express about new business models in gaming. As a self-described traditionalist when it comes to sports, he said he tends to be a grumpy old man whenever new rule changes are introduced. However, he also said he was open-minded enough to understand that things will change, and just as American football fans have come to embrace once-controversial innovations like video replay, so too does he think gamers will come to look back at the disruptive changes the game industry is going through and conclude they were for the better.

"I think the core audience that dislikes the fact that there are play-for-free games and microtransactions built into those... fine, I get that," Moore said. "As you know, I read all the stuff, and it is the most intelligent commentary on the web as regards games. There's no doubt about that. But every now and again, and you've seen me do it, somebody will come in there and say something stupid that I think is beneath the site itself and beneath the industry."

While Moore can be compelled to join the comments section on occasion, he sees the trends at work as being beyond one person's ability to impact.

"I don't think anybody has to like it," Moore said. "I think that's where it goes. It's like me; I get grumpy about some things, but if the river of progress is flowing and I'm trying to paddle my canoe in the opposite direction, then eventually I'm just going to lose out. From the perspective of what needs to happen in this industry, we need to embrace the fact that billions of people are playing games now."

For more of Moore, check out the first part of the interview, which ran yesterday.