Capcom tries again with Monster Hunter Stories 2 -- but why?

Capcom slips another quarter into the machine and makes a play for Japan's kids market

When it was announced in 2015, Monster Hunter Stories seemed like the perfect game for the Japanese kids' market.

It was based on an existing brand that was already immensely popular with a wide age group. It used the same eye-catching monster designs as the ever-popular main series, but let you buddy up with the monsters instead of mutilating them. And it was a turn-based RPG, meaning it was approachable enough for anyone that couldn't keep up with the reflex-heavy combat of mainline Monster Hunter. It was colourful, visually striking, and promised a wealth of hidden depth to discover. It had an anime tie-in on a popular TV channel. It had an Amiibo figure. It had a trading card game. It had the power of friendship.

Monster Hunter Stories was the perfect game on the perfect platform, being released at the perfect time

It was Pokémon, but with Monster Hunter's well-known and eclectic roster of dragons, giant bugs, and poison-farting baboons. Most importantly, it was on the Nintendo 3DS, which had a stranglehold on the kids' market in Japan.

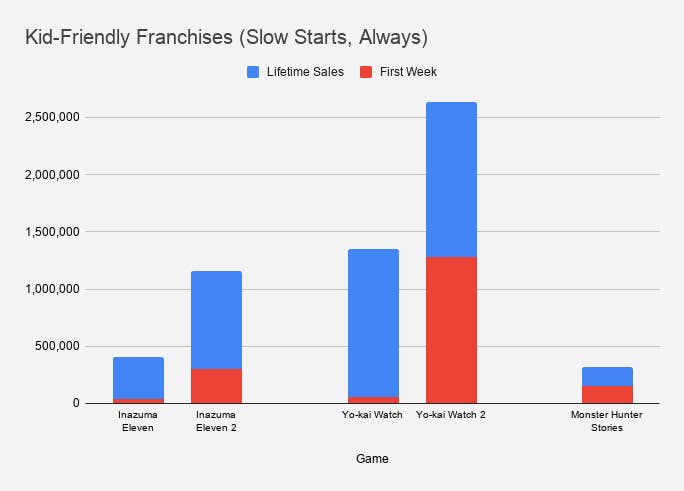

For all intents and purposes, Monster Hunter Stories was the perfect game on the perfect platform, being released at the perfect time. Yo-kai Watch was bigger than ever, and had primed the market for more monster-taming games. Pokémon, despite its aging audience, was still going strong. Dragon Quest Monsters was still a thing. Meanwhile, the mainline Monster Hunter series had graduated from the PlayStation Portable to the 3DS, and Monster Hunter 4 was already one of the most popular games on the device.

In theory, Stories should have ridden the coattails of the main series and introduced the brand to a whole new generation of kids, reaching the kind of demographic that mega-franchises like Pokémon and Dragon Quest enjoyed. That never happened.

The first signs that Monster Hunter Stories wouldn't set the sales charts on fire came a week prior to the release of the game, when tie-in anime series Monster Hunter Stories: Ride On debuted on Fuji TV. Ride On's first episode aired at 8.30am on a Sunday morning -- generally considered a prime spot for children's programming -- but ratings were low and the show failed to make it into the top ten animated shows for the week. TV ratings tracker Video Research Ltd. would subsequently report that the next several weeks of animated programming were dominated by the usual suspects, with shows like One Piece, Dragon Ball, Yo-kai Watch, and even international shows like Shaun the Sheep, all featuring consistently in the top ten, but no Monster Hunter Stories.

In parallel, Japanese retailers began reporting that the 3DS game was seeing low pre-orders, and that the anime airing simultaneously wasn't doing much to move the needle. When Monster Hunter Stories was released a week after its anime counterpart, video game sales tracker Famitsu reported that it had sold just 215,000 copies in its first eight days on store shelves -- quite a bit lower than any industry guru would've predicted.

Monster Hunter Stories was an excellent game, and its poor performance in Japan remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of the 2010s

Interestingly, another sales tracker, Media Create, reported that Stories had sold primarily to adults, rather than children, meaning it wasn't reaching its intended audience at all. Capcom's carefully-crafted merchandising blitz -- including a trading card game developed by Bandai -- did little to turn its fortunes around in the weeks that followed. As good as the game was, the audience at large just wasn't interested.

Monster Hunter Stories would go on to sell just over 300,000 copies at retail over the course of its life. Not too shabby for the smaller Japanese market, but very obviously not the kind of numbers Capcom was hoping for, given that the main series consistently sold in the millions. Stories would subsequently be ported to iOS and Android devices a year later, and Capcom would even use it to help promote a vehicle crime awareness campaign organized by the Osaka Prefectural Police in 2017. And then, Monster Hunter Stories disappeared from the public eye.

The unfortunate through line that remains in all this is that Monster Hunter Stories was an excellent game, and its poor performance in Japan remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of the 2010s. Looking back, one could hypothesize that perhaps the anime wasn't good enough to get kids invested. Or perhaps they just weren't into the idea of yet another monster-taming franchise after five years of Yo-kai Watch mania. Or maybe kids simply observed that "onii-chan" [Translator's note: "Onii-chan" means big brother] was into the big-boy Monster Hunter games, and wanted a piece of that action instead.

Whatever the case, Capcom must have some inkling as to what went wrong, or it wouldn't be reviving Monster Hunter Stories on the Nintendo Switch -- and with a brand new game, at that. Judging by its trailer, Monster Hunter Stories 2 appears to be a fairly major investment; it looks like an extremely polished, sprawling affair with an expansive world and all the requisite twists, turns, and emotional drama you'd expect out of a JRPG. It obviously isn't going to be as big-budget as, say, Final Fantasy or Persona, but it's certainly a cut above the usual "AA" fare one sees from smaller studios like Falcom and Nippon Ichi. What that tells you is Capcom believes this game has an audience.

It's an intelligent supposition -- one that's cognizant of the fact that every mainstream franchise, from Animal Crossing to Pokémon to Mario, has seen growth on the Switch, and that this should theoretically apply to Monster Hunter in all its forms as well. Both Monster Hunter: Rise and Monster Hunter Stories 2 are likely to reach new audiences on the platform, just because it's so well suited to longer, grind-heavy games that require several hours of investment, particularly in Japan where the vast majority of people that play games do so on portable platforms.

Capcom understands all too well that launching a children's brand in Japan can be dicey business

There's also the fact that Yo-kai Watch, Inazuma Eleven, and other brands that have historically enjoyed immense popularity among Japanese kids have fizzled out, meaning that there's room for a new player to enter the market. Who better than Capcom, which already controls one of the most popular video game brands in the country?

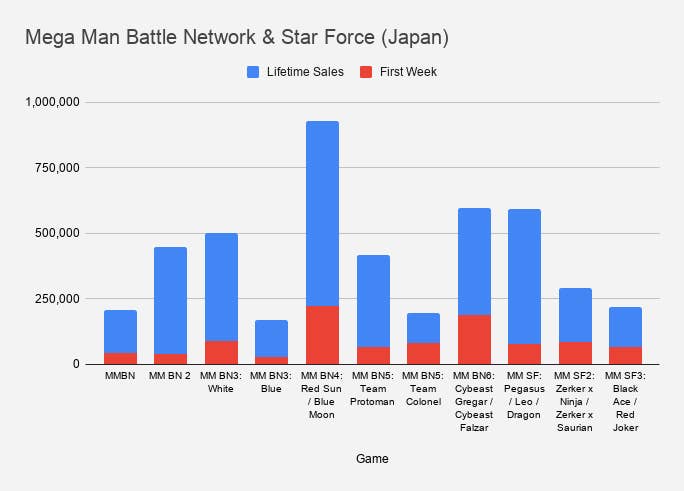

Of course, that's easier said than done, as Capcom no doubt understands. While the company hasn't been a player in the kids' market in over a decade, the Capcom of 2001 -- back when it was under Keiji Inafune's leadership -- specifically developed its Mega Man Battle Network and Mega Man Star Force brands to appeal to children. Battle Network performed exactly like every other major property aimed at kids, with slow initial sales eventually snowballing into something much bigger as more and more children discovered it through word of mouth, the Japanese magazine CoroCoro (an essential publication to be in if you're a kid-friendly franchise), and the tie-in animated series.

Unfortunately, Capcom approached Battle Network the way they had every other Mega Man sub-brand -- with an overzealousness that led to iterative, annualized games that eventually bored fans. The series peaked with Mega Man Battle Network 4 in 2003, just three years after it had begun, and sales tapered off over the following five years until 2008's Mega Man Star Force 3 killed the brand for good. Children, as Capcom learned, aren't easily impressed, and there's no shortage of other shiny things vying for their attention.

Capcom would subsequently exit the kids' market, relinquishing it to rival publisher Level 5, who would do a much better job of managing its IP. Level 5 would successfully predict what kids wanted out of their multimedia behemoths for six straight years, enjoying immense success off the back of brands like Inazuma Eleven and Yo-kai Watch. The company would go on to amass an enormous following on the Nintendo DS and Nintendo 3DS in Japan, even catching the eye of Nintendo, which would strike a deal to publish its games overseas.

Level 5's success didn't go unnoticed. After watching from the sidelines for five years, Capcom would finally have another go at the kids' segment in 2013, with the announcement of a brand new franchise: Gaist Crusher, developed in collaboration with Ikaruga developer Treasure, was announced as "the start of a major project for children's content" in the spring of 2013.

Capcom set its sights squarely on the elementary school boy demographic, crafting a game, comic series, anime, and toys, all meticulously designed to launch what it hoped would be a new long-term multimedia franchise. In a press release to investors, Capcom stated that with the number of children in Japan declining, it hoped to use Gaist Crusher to attract interest in new brands and "firmly establish" them using a wide variety of media.

It didn't work, and Gaist Crusher went on to sell less than 100,000 units in Japan over the course of its life. The game was never localized for the West, and its failure marked the last couple of projects Treasure ever worked on, going from a developer of cult favourites to merely a license holder. Looking back, it all feels like an enormous waste of time and money.

This brings us squarely back to Monster Hunter Stories. Capcom understands all too well that launching a children's brand in Japan can be dicey business. Most Japanese publishers do. Pokémon Red and Green famously sold somewhere in the vicinity of 100,000 to 150,000 copies in their first week, gradually snowballing until they caught on, purely by chance. Both Inazuma Eleven and Yo-kai Watch took until their sequels to catch on as well, and for every brand that eventually did catch on, there are three others that didn't. To top it off, the Japanese games industry has been in heavy decline for over a decade now.

And that's why Monster Hunter Stories is getting a second chance -- because, again, it's already part of a proven entity. Absolutely nobody is going to question Capcom investing in what is literally its biggest brand at the moment. In fact, it would have been more surprising if Capcom hadn't given Monster Hunter Stories another shot, given how well suited Monster Hunter's world is to different interpretations. And if it were to fail again? No harm done. The company can write it off as an experiment -- a relatively small gamble in the grand scheme of things, and all part of maintaining a multimillion dollar brand.

But that obviously isn't what Capcom wants.

That's why it will need to make sure its marketing and understanding of the audience is on-point this time around. Whatever went wrong in 2015 -- and I honestly couldn't point to one specific thing -- it can't happen again. Perhaps that's why all the characters in Monster Hunter Stories 2 look a little older than the first game -- because Capcom has looked deep and discerned that children don't want a "kiddified" version of Monster Hunter after all. They want whatever big brother is into. And so, maybe, the solution is to target that big brother instead, and let it trickle down to the younger sibling. It just might work.

And who knows, perhaps Monster Hunter Stories 2 will find greater acceptance among western audiences as well. The Switch userbase is keen on JRPGs, keen on Monster Hunter, and clearly hungry for more games from third-party publishers. Things really could work out differently this time around.

Individual sales figures sourced from Famitsu via Game Data Library. Graphs by GamesIndustry.biz.