Can we please make sure that mobile VR won't suck?

Mobile is the next, and arguably most important, frontier in the rollout of virtual reality, says SuperData's Joost van Dreunen

Given the widespread adoption of smartphones worldwide, mobile is going to be the platform on which most people are going to first experience virtual reality. Let that sink in for a moment. Despite the focus on the Oculus, which promises fantastic resolution and visual experiences, no one currently owns any devices yet. Pre-orders have started, but the industry has yet to find out what consumer adoption will look like. Meanwhile, there are 1.3 billion mobile gamers out there. The high-end devices are expensive, priced between $599 and $799, are more complicated to set up, and require a much more powerful PC rig to get the necessary frame rates to make the experience seamless.

Smartphones on the other hand require only a simple download to get a first glimpse at VR. Already Google has shipped 5 million units of its cardboard, which is cheap and universal in its use. And big brands like Coca-Cola and McDonald's are hip to the trend. When the fast food chain began selling its Happy Goggles, it was a clear sign that marketers are now well-aware of the sparkly promise of virtual reality and are leveraging its novelty to sell, among other things, soda pop and hamburgers.

The issue is that we, as a creative industry, have to deliver on the promise of virtual reality.

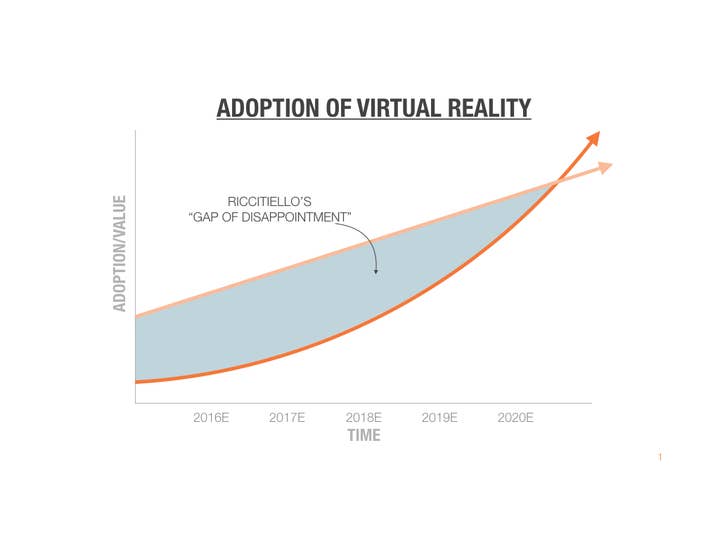

With a growing number of companies, ranging from investors to advertisers, fueling the VR fire, we can anticipate a market correction. Specifically, when the various mobile VR devices start to arrive and people begin to first experiment with its capabilities, it is likely that this may be somewhat disappointing.

Recently, Unity's CEO John Riccitiello pointed to the immanent disenchantment that is likely to follow the current hype cycle. As a veteran from the games industry, he is all too familiar with the difficulty of rhyming what people expect with what is possible, and issued a sober reminder that the first few years of VR may prove disappointing.

Worse, history may even be repeating itself. Following a sudden boost of investment that hoped to satisfy a seemingly limitless appetite for interactive entertainment, the games industry collapsed under its own expectations in 1983. A slew of crappy devices and terrible content managed to evaporate consumers' willingness to spend, thereby decimating the market's value. What ultimately salvaged the industry was Nintendo's insistence on tightly curated quality content.

"The role of mobile game developers is changing, because they are now in the position to determine for a large number of people what their first virtual experience will be"

Fast-forward to mobile VR, we already observe many developers looking to quickly occupy their own corner in the market. The emergence of a new platform creates a powerful and rare opportunity for, especially smaller, dev studios to stake a claim. It was the release of the iPhone that allowed Rovio to become the poster child of mobile gaming success during its early days. What Rovio did well was to use the platform's features, produce something that stood out in quality, and make its game's mechanics transparent to the millions of people who had never considered themselves to be gamers, let alone on a smartphone.

The hardware manufacturers are also putting in their bids. Unfortunately, here, too, not everyone is equally successful. A recent reviewer of the LG 360 VR, designed exclusively for its G5 phone, found it to be "one of the shittiest virtual reality devices I've ever tried." It is experiences like these that may very well set the tone for a large number of consumers when they find they cannot reconcile what they thought mobile VR was going to be like and what it actually is.

The role of mobile game developers is changing, because they are now in the position to determine for a large number of people what their first virtual experience will be. It's an incredibly difficult problem because game design, like all design, is about dealing with limitations. But right now VR is at its most exciting and pregnant with possibility. We can let our creativity run free in an untouched hyperreal realm of awesome experiences and infinite commercial success. Designers, publishers and hardware manufacturers do not have to adhere to competitive market forces, industry patterns, rising marketing costs, discovery issues, distribution problems or franchise restrictions. At least, not quite yet. And because none of that exists right now, mobile VR is untainted by everything that makes developing great experiences so challenging.

So the question before us: what do we want people's first experience with mobile VR to be?