Subscriptions are the future - but nobody agrees on the details | Opinion

Industry consensus over the growing importance of this model disguises deep disagreements over how it will actually work

A broad consensus seems to be building around the idea that the industry is transitioning towards a more subscription-based business model -- led by services like Game Pass, the upcoming revamp of PS Plus, and whatever alternatives are being cooked up by the likes of Amazon and Valve.

It's not the most harmonious of consensuses, though; no two companies see this subscription-based future quite the same, with significant underlying disagreement on the roles that will remain for up-front purchases and other business models; the bigger third-party publishers definitely imagine a future role that's very different to being a passive supplier of subscription service content to Sony and Microsoft.

Even as almost everyone comes around to the notion that subscription services will play a big role in the future of the industry, then, there are some pretty major battles ahead about exactly how that's going to be realised and what it's going to mean for everyone involved.

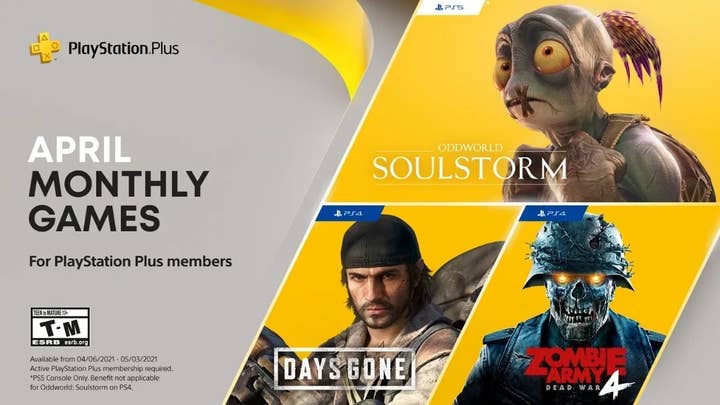

We got a sneak preview of one of those upcoming battles this week, in the form of comments from Oddworld founder Lorne Lanning on the Xbox Expansion Pass podcast. To be clear, Lanning isn't being combative or accusatory in his comments, lamenting the "devastating" effect on sales of Soulstorm which the company saw as a consequence of accepting an up-front deal to put the PS5 version of the game on PS Plus in its launch month.

We should gird ourselves for a messy public fight over percentages and engagement calculations, because arguments over how this new pie is sliced up are only getting started

There's no suggestion that Sony is somehow the villain of the story for its offer, which Oddworld saw as a good deal that provided some welcome financial stability while also being more money than they expected to make from the projected 50,000 to 100,000 sales for the game on the then-new PS5 console. Even acknowledging that the deal they took was more than fair, though, they can't help the crestfallen feeling that results from seeing the title downloaded more than four million times through PS Plus -- vastly, vastly more than they'd ever expected when they signed up to the deal.

Nobody's in the wrong here, but it's certainly easy to sympathise with Lanning's position and his feelings about the impact the PS Plus miscalculation may have had on Oddworld's game. Any developer which takes a flat-rate deal on the expectation that it'll account for a hundred thousand downloads at most, only to see 40 times that number clocked up without any additional compensation, is going to feel pretty devastated by the missed potential.

A surface reading of Lanning's comments suggests a few areas where a miscalculation about the impact of including the PS5 version of the game on PS Plus at launch might have happened. Oddworld may have somewhat overestimated the impact that stock shortages were having on PS5 sales, as while demand has consistently outstripped supply, the supply itself hasn't actually been terrible by industry standards, and PS5's installed base has grown faster than any previous generation of consoles even as the headlines have been filled with complaints about empty store shelves.

Equally, the company may have misjudged how consumers engage with their monthly 'free' games on PS Plus; subscribers who hadn't managed to get a PS5 yet could still relatively easily bank a free PS5 version of Soulstorm in their library in anticipation of playing it on the new console at some point in future. That's a huge disincentive to buy a PS4 version of the game; having a different version sitting for 'free' in your game library, even if you can't play it just yet, is a tough psychological obstacle to overcome for anyone thinking of buying the game at launch. Sony's subscription services are also likely to create a similar problem for its first-party launches once the revamp kicks in this summer, despite the platform holder confirming its new titles will not be added to PlayStation Plus on day one; many consumers have pretty good impulse control when it comes to buying things they know or even strongly believe they'll be able to play for free relatively soon.

In some ways, the issues Oddworld encountered here are a pretty specific set of problems -- but in others, they are a preview of some of the broader issues around subscription services that have been setting mental gears turning around the industry for some time, and are likely to turn into a battleground in the coming years.

First and foremost, there's the question of how creators are compensated for their games being available through subscription services. Lump sum payments like the one Lanning suggests Oddworld received for Soulstorm on PS Plus aren't all that unusual at the moment, and for developers reaching the end of their financial tethers as a long and expensive development process comes to an end, the offer of a decent lump-sum that eliminates risk from the equation can be a very welcome one. It would be interesting to know if a higher risk/reward deal was ever actually on the table in this case, but it would be hard to blame a developer for taking the lower-risk option even if that were the case, and especially given their prior beliefs about likely sales figures.

However, those kinds of lump-sum payments aren't going to be the default for these kinds of contracts in future -- at most, they'll be enticements for companies whom the platform holders want to entice into some form of limited exclusivity. Instead, a revenue share based on engagement feels much more likely to be the future of how compensation for creators is calculated. For developers, this is much higher risk (although this can be alleviated somewhat by an advance system, with royalties / residuals only being paid after the advance is cleared), but it also means that developers who create runaway successes aren't left holding their lump sum in one hand and a large glass of regret in the other.

Revenue share on engagement is a big transition away from up-front payment, and will introduce potentially unwelcome changes to how developers create their games

Revenue share on engagement is, however, a major transition away from the up-front payment model for games, and it'll introduce some potentially unwelcome changes to how developers are incentivised to create their games. Engagement and retention will become the be-all and end-all of commercial success, driving another nail into the coffin of short, compelling game experiences -- but this remains arguably the only fair way to create a compensation structure for subscription gaming. Downloads, after all, are more an indicator of how well-marketed a game is rather than anything else; clicking the download button on a game you have to pay for is an incredibly low-cost action for most consumers, and all it takes is a good trailer, a funny description or an interesting name to get to that point in many cases.

By contrast, engagement -- the hours, minutes and seconds players actually spend in a given game each month -- gives a relatively fair estimate of how much that game contributed to the consumer's decision to renew their subscription at the end of the period, even if it does over-value some kinds of game (especially service-based online titles) while demoting shorter but nonetheless high-quality titles.

That leads on to the other broad issue that's hinted at by Lanning's comments -- namely that we're probably about to see a massively contentious argument emerge in the industry over the actual value of a download, or an hour of engagement. Oddworld is lamenting seeing four million downloads of a game for which they accepted compensation based on around 100,000 sales -- but the question of how many of those downloads happened precisely and solely because the game was offered for free is one to which there's really no good answer.

This is a decades-old argument across many media industries; when digital piracy emerged in the 1990s, media companies claimed that every pirate download of a game, movie or album was equal to full-RRP lost revenue, when in reality only a fraction (perhaps quite a small fraction) of pirate downloads would ever have translated into a full-price sale in the absence of a pirate copy.

In the context of piracy, this was something of an academic argument. Wildly over-inflated estimates of industry losses to piracy were an annoyance to anyone with even the most rudimentary understanding of statistics, but everyone still broadly agreed that piracy was problematic and damaging, and over-inflating the numbers didn't do any actual harm beyond occasionally convincing some gullible executives to pay over the odds for anti-piracy technology of extremely dubious worth.

In the realm of game subscriptions, though, the question of how many 'free' downloads on a subscription service it takes to displace a full-price sale is absolutely crucial. Oddworld knows, of course, that four million downloads on PS Plus doesn't mean the company lost four million sales -- but it seems to feel strongly (perhaps with some justification) that the ratio of free downloads to full-price sales is quite a bit less than 40:1.

That may or may not be true; it's a counter-factual we'll never actually be able to test in any sensible way, but the perception of what constitutes a 'fair' estimate of that ratio (or of the even trickier ratio, 'how many hours of gameplay on a subscription service add up to the displacement of a single full-price copy') is enormously important. If companies start to feel strongly that the ratios aren't calculated fairly -- that they're losing money through being part of a subscription service -- well, there's still time even for services as ambitious as Game Pass to end up being more or less a home for a handful of first-party games, some superannuated third-party back catalogue games, and little else.

Whether publishers pulling their recent games would even work to preserve their launch revenues or put pressure on subscription platforms for more generous revenue shares, however, is a trickier question. Many music companies loudly decry the revenue share they receive from Spotify and Apple Music, yet every attempt at pulling popular music from those services has merely hurt both artist and publisher -- a power imbalance that game publishers will be desperate to avoid, but which may nonetheless be inevitable.

A tug-of-war between subscription service operators and publishers over pricing and revenue sharing would probably even result in bigger publishers taking their ball and going home to set up their own rival subscription services -- the Paramount Pluses and HBO Maxes to Microsoft and Sony's Netflixes and Disney Pluses, as it were -- causing fragmentation that might ultimately benefit nobody involved.

For all the assumptions we make about game subscription services being the future of the industry, there's still a lot that's uncertain about how the financial and commercial side of those services is going to work. Even at this early stage, not every company that's had a high-profile game on a subscription service feels happy about how the experience turned out -- and consensus about the importance of game subscriptions is merely a veneer over a pretty contentious set of disagreements over the way things are going to work and the roles different companies will play in this new ecosystem.

Getting revenue shares and contract terms right is going to be a job that takes years, and no side will ever fully be satisfied; we should gird ourselves for a messy public fight over percentages and engagement calculations, because the arguments over how this new pie is sliced up are really only getting started.