Are bootleg game soundtracks damaging the industry?

The popularity of video game music clashes with its lack of availability in physical formats -- we examine both sides of this complex issue

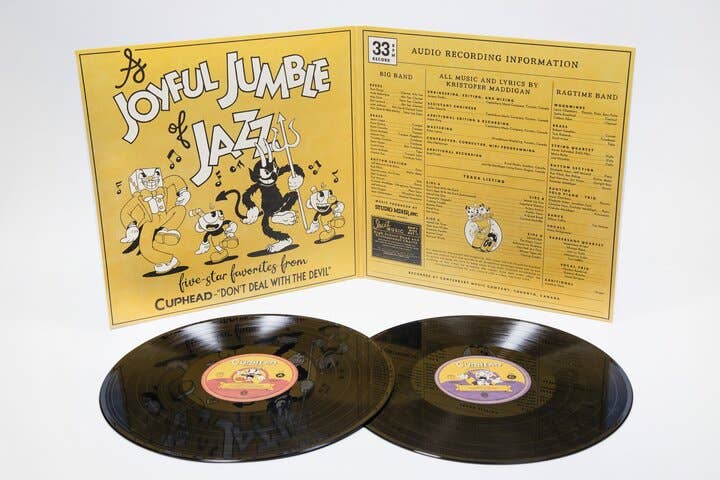

Your favourite video game soundtracks can also be listened to as vinyl records.

While the vinyl boom of the 2010s contributed to the formation of several new startups specialising in video game records, it isn't a recent phenomenon. The relationship between video game music and vinyl goes as far back as 1978, when Japan's genre-defying Yellow Magic Orchestra released their revolutionary self-titled album, which capitalised on the buzz of a rapidly-growing arcade scene by being the first album to sample video game music and sound effects. Six years later, band member Haruomi Hosono released a ten-track LP featuring music from games such as Pac-Man, Dig Dug and Galaga -- the world's first release of a video game soundtrack.

Hosono's fusion of electronic music and video game music posed an important question, the possibilities of which are still being explored by game companies today: what happens when we take the music from the video games that people spend hours playing every day, and present it to them in a format outside of the game?

"The last two or three years it's really exploded"

Frederik Lauridsen, Blip Blop

Sega, Namco, Nintendo, Konami, Sony, Capcom, and many more have spent the last 30 years experimenting with the weird and wild, ranging from an F-Zero arrangement album featuring Marc Russo of the Doobie Brothers on saxophone, to live festival performances from Sega's in-house SST band. More than 100 video game soundtracks were released on vinyl throughout the 1980s, mainly in Japan, according to the Video Game Music Database. And while CDs may have reigned supreme throughout the '90s, the vinyl format has proved to be the king in 2020.

In 2019, 4.3 million LPs were sold, with sales up for the 12th year in a row, according to the British Phonographic Industry. With music consumption up for the fifth year in a row, more and more video game publishers are working with labels to release their soundtracks on vinyl -- but not all of them.

Music popularity is never too far from music piracy, and vinyl records aren't immune to the problem. Bootleg or counterfeit records -- unlicensed records which are sold without the permission of the rights holders -- have been around since the '60s, but a growing number of bootleg labels are now emerging within the video game music scene, illegally manufacturing and distributing video game soundtracks that haven't been made available by game publishers.

Frederik Lauridsen has spent the last five years cataloging and archiving video game vinyl records on his website Blip Blop. He believes bootleg records make up as much as 10% of the video game music (VGM) market, counting the different variants and colour pressing for each record.

"The last two or three years it's really exploded," he says.

Lauridsen counts around 180 individual bootleg records released by 28 bootleg labels and individuals. These numbers have been gathered from information on Discogs, online marketplaces such as eBay and Amazon, and social media sites.

Numbers are becoming more difficult to track, as most bootleg labels are being more discreet about how they operate, selling their records through invite-only groups, private Instagram accounts, and mailing lists. Others are easier to find, operating through online stores that are primarily run through the online storefront, Big Cartel.

"There's a newer trend of not crediting the label behind a release on the release itself in order to obscure the origins," Lauridsen says.

Is piracy an accessibility problem?

Bootleg records are a divisive issue across the video game music community. Some groups have banned the discussion of bootleg records to discourage purchases, while other groups -- often private -- serve as a discussion point for the subject.

"By saying: 'We don't want to put this out,' it gives up control. It has this counterintuitive effect"

Sebastian Wolff, Materia Collective

While many collectors, like Lauridsen, are against bootlegs, there's no denying their popularity among certain VGM enthusiasts.

A niche product within a niche community, bootleg VGM records can also sell for extortionately high prices -- especially rare test presses, which have sold for upwards of $1,000. Most bootleg labels sell their records for between $20 and $40 to a limited number of people, but scalpers and resellers cause prices to skyrocket when they're resold to the general public.

"The closed Facebook groups where they sell bootlegs are filled with scalpers and resellers," Lauridsen explains. "Bootleggers aren't the only ones making good profit on these. Since you have to be in a closed group to buy these in the first place, a lot of people know they can sell these bootlegs to people who aren't in the groups. It's not unusual to see bootlegs being sold at two to three times their initial price not long after they sell out."

The most popular bootleg records are Nintendo soundtracks. While legitimate VGM labels such as Iam8bit, Laced Records, Brave Wave, and Materia Collective have established strong relationships with publishers such as Capcom, Sega and Konami, Nintendo has been less enthusiastic about bringing its back catalogue of music to vinyl.

Sebastian Wolff, co-founder of Loudr and owner of Materia Collective, believes that music piracy has always been an accessibility problem, and Nintendo's unwillingness to publish its music isn't helping.

"Fans of something want to be able to celebrate what they're passionate about on their platform of choice," he explains. "Someone who's a big fan of Donkey Kong Country, if that [music] is not on vinyl, it will be put on vinyl if the powers that be don't do so. If a soundtrack is not available for streaming, someone will put it up on SoundCloud or on YouTube. The thing I've been preaching to rights holders and games companies for the last decade is to work with music rights partners and experts that understand this market.

"For the companies who care a lot about having control over their IP, I think it's fascinating that none of them proactively invest in controlling that on the music side. Because by saying: 'No, we don't want to put this out,' it gives up control. It has this counterintuitive effect."

We contacted David Wise, composer of the Donkey Kong Country series, for his thoughts on the bootleg records of the franchise that are being circulated.

"The reality is that where an official release exists, bootleg albums deprive the publisher and the artist of revenue," he says. "Revenue that they might have been able to use to produce more music. These records are not the official soundtracks.

"That said, I feel Nintendo is missing a potential revenue stream here. Hundreds, probably thousands of people have asked me personally why there isn't an official album. Fans of products always want the 'official' merchandise, and I know people have purchased these [bootlegs] because no official release is available."

Bootleg records have an impact on legitimate VGM labels

Legitimate VGM labels can spend years working on the release of a soundtrack. As well as the time spent acquiring the rights for a vinyl release -- one of the more costly areas of vinyl production that can take months of delicate negotiations -- labels also need to pay for an engineer to source the audio in its highest quality and extract it; a studio to master that audio and make it suitable for a vinyl release; an artist or designer to create packaging artwork; and the pressing plant to manufacture the vinyl, usually a couple of variants. Some licenses require royalties to be paid from each release, too.

Both fans of video game music and VGM record labels have varied opinions when it comes to bootleg records.

"Hundreds, probably thousands of people have asked me why there isn't an official album"

David Wise, Donkey Kong Country composer

"They fill an unfortunate need," Wolff says. "I wish that I could say that they have inspired official releases, but I've actually seen the opposite. There's been two occasions where ongoing discussions with a licensor had been halted after discovering bootleg records were already being circulated.

"In both of these cases, we made the potential clients aware and we mutually agreed on simply not continuing that discussion. I know of a couple of other labels to whom that's happened, and when you think about even just employee time, you spend 50 hours putting together a pitch and communicating then it just kind of goes down the drain."

Other labels, such as Iam8bit, haven't experienced these problems. Amanda White and Jon M. Gibson, the founders of Iam8bit, tell us over email: "We've never run into a wall because of the existence of bootlegs. If anything, the prevalence of bootlegs for certain albums merely highlights the popularity of that particular soundtrack, and might inspire us and the IP holder to team up to release it officially."

Alex Aneil, CEO of BraveWave Productions, believes that while bootleg VGM records are a problem, they're not a huge factor in the grand scheme of things.

"I would say YouTube uploads that aren't properly monetized are probably a much bigger problem in the long run, or people illegally sharing video game music," he says. "As a label that does vinyl, CDs and digital, I'm actually more apprehensive about illegal YouTube uploads and FTP servers than I am with specific bootleg records."

Why aren't bootleg video game soundtracks harder to find online?

Releasing music on vinyl, while expensive, isn't that difficult. There are thousands of pressing plants and vinyl brokers all over the world offering their services. Most of them will ask you to sign a declaration form -- or several forms in some cases -- to confirm that you own a license for the music you're submitting. Some companies will ask for additional information to prove a license is owned. Others won't. The lack of checks by some companies has made it possible for bootleg labels to simply lie on these forms.

"Some plants are more strict than others about this kind of thing," explains Aaron Hamel, co-founder of Ship to Shore Records. "I know that some plants will actually ask for a copy of a contract that's been signed."

Ultimately, it's up to pressing plants, and the brokers of deals between labels and pressing plants, to ensure the label has the rights to the music they're pressing.

"I think the average person who's checking for this at the manufacturing plants, or the people who do test presses or who do the plating of the mother discs, they're not necessarily privy to the complex rights management of video game music," Aneil suggests. "I think if someone orders a test pressing of something illegally, the person on the other end is not going to scrounge the internet to see if this music is actually being used legally or not. They probably assume it's entirely original music or they've done their due diligence otherwise."

"The prevalence of bootlegs for certain albums merely highlights the popularity of that particular soundtrack"

Iam8bit

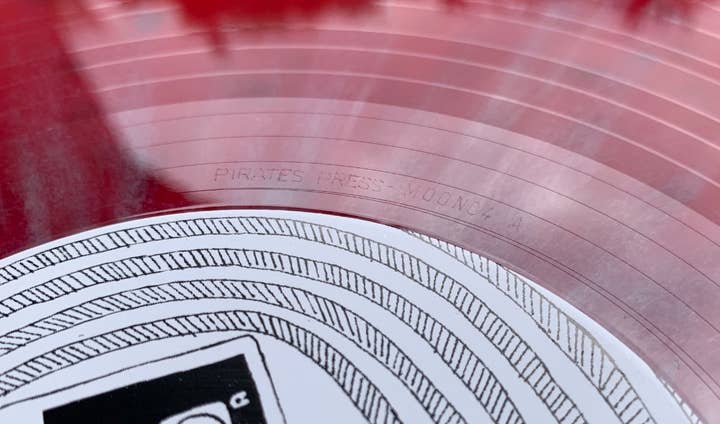

Some records have codes and information etched into their run-out groove, which can be used to identify manufacturing information such as where the record was pressed. We've obtained images of several bootleg records which clearly identify GZ Media, one of the world's largest vinyl manufacturers, and Pirates Press, an independent vinyl manufacturer, as the manufacturers of records from one of the most notorious bootleg labels.

We asked Eric Mueller, owner of Pirates Press, if he was aware of this label. He responded with the following:

"I'm not familiar with that label specifically. We press hundreds and hundreds of titles per week, and all of our customers must submit an IPR ownership declaration for each title they press (and supplemental mechanical licensing paperwork if they claim not to be the owner of any part of the material being produced). That said, human beings have been known to lie from time to time, and while we do our very best to scrutinize our customers' paperwork and materials to make sure they are as legit as possible, it's of course possible that someone's false statements/actions could slip through and result in an unauthorized product.

"We hope that is not the case, and have not had this specific instance brought to our attention before now. I will of course circulate the label name and release info around with everyone on my end and the factory's as well, to make sure that everyone is aware and that this concern is addressed formally."

We also contacted GZ Media for a statement, and will update the article with any response.

The availability, past and present, of bootleg video game records suggests that record stores aren't carrying out due diligence either. Turntable Lab, a popular online music store based in New York, lists a variety of bootleg video game soundtracks for sale on its online store. In 2016, a press release was issued by Turntable Lab announcing the launch of Junichi Masuda's Gameboy soundtrack for Pokémon Red and Blue. No details were provided about the authenticity of the record and the story was picked up by more than a dozen mainstream websites. We contacted the CEO of Turntable Lab, Peter Hahn, to ask if Turntable was aware that it was selling bootleg records, but we did not receive a response.

It's unlikely that the majority of these rights holders are aware of these bootleg records, so why aren't companies doing anything about them?

"You have to pick your battles," Iam8bit's founders say. "Big companies only have so many lawyers to send cease and desist letters out. While we can't speak for the IP holders, our guess is that they don't see bootleg albums as a tremendous threat to their overall business, because if they did, they would have acted very aggressively to squash it by now. We like to imagine they share our perspective, where most fans are bootlegging very innocently, and that when the time comes for official releases, those same fans will follow and gladly purchase the high quality official stuff."

Wolff adds: "I think a lot of these game companies are weighing a potential PR disaster against the benefit of shutting down what is considered by many fans to be a fan-work. I've spoken to audiophile fans who just want to celebrate their favorite music or their favorite game on vinyl. If it's not out there officially, it will be made available unofficially. And for them it is the second best thing."

What are the intentions of bootleg record label owners?

In the case of Nintendo, it seems strange for a company that has a reputation for protecting its IP through DMCA takedowns against fan games to do nothing about its soundtracks being circulated as bootleg records, whatever the intent of their creators.

"I make no profit and lose money on this all the time, but when people are happy -- that makes me happy"

Bootleg label owner

Fans of bootleg records often justify their purchases by saying that these records would have never been created otherwise. Those who are against them will criticise the owners of bootleg record labels for taking money from video game composers illegally. For others, there's a moral debate surrounding the intentions of an individual manufacturing, say, five records for their close friends, to a label creating and selling bootleg records in their thousands.

The owner of one bootleg record label, who doesn't want to be named, tells us over email: "I can tell you that I started doing this because I love vinyl/video games and I love the idea of making something that people want but can't have through normal means. I make no profit and lose money on this all the time, but when people are happy -- that makes me happy."

One of the largest VGM bootleg record labels claims to send its profits to the creators of music where possible, or to other charitable causes. We reached out to this record label, which did not respond, so it hasn't been possible to verify the charity donations.

However, we did contact Jim Andron, who composed the music for Tetris on the Phillips CDi. This soundtrack was released without a license and without Andron's permission, with the label owner making a promise online that any profits would go directly to Andron.

"He [the label owner] did release it without my permission," Andron tells us over email. "But as I went back through old correspondence, I found an email from several months back (unread) where he told me about it and asked if I'd be involved."

Andron went on to say that he has been sent "generous royalties" for the project and that the "amount of royalties was a nice surprise."

The quality of bootleg records can vary a lot, collectors tell us, ranging from bootlegs that have similar audio quality to legitimate records, to others with noticeable imperfections such as skipping and degradation. The time spent on creating these records varies from label to label too. Some bootleg records are the result of somebody taking a video game soundtrack from YouTube and getting it cheaply manufactured.

Without the cost of a licensing fee behind them, bootleg labels can generate a lot of profit, especially those pressing larger quantities of records. As what these labels are doing is illegal, people who order bootleg records could easily find themselves out of pocket if a label is shut down or can no longer proceed with orders. Many VGM fans have been burned this way before.

"A lot of bootleg records feel like cash grabs to me," Hamel from Ship to Shore Records says. "When you're charging $25 or $30 dollars that you're not putting any licensing into, you're making a pretty handsome profit. I just don't agree that people have the right to profit on these types of things."

Music piracy will always be a problem, and as the demand for vinyl shows no signs of slowing down, it's unlikely that the popularity of bootleg records will suddenly waver. One of the easiest ways to address this is by closing the gap between the music industry and the video game industry. If video game companies can spend more time working with music rights experts -- and this is across digital formats, too -- more creators will be able to benefit from the popularity of video game music.

Wolff says he isn't suggesting that companies start taking legal action against bootlegs, but he does believe that the existence of bootleg records is doing significant damage to the legitimacy of video game music, which can be difficult for passionate bootleggers to see.

"We care about the quality, we care about the legitimacy, we care about things being done right and we hope that more people join us on that vision. Want to make a vinyl? Start a label, get in touch with people, do the negotiations. Making records is hard. Doing it legitimately is even harder."

We contacted ten bootleg record labels and received a reply back from one. Nintendo did not respond to a request for comment.