Getting the hate out of games

ADL's Daniel Kelley says the industry can learn from social media to make communities welcoming to more players

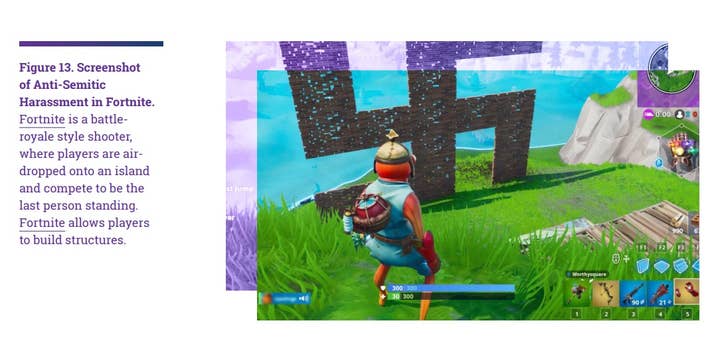

In the fight against hate and harassment, the games industry is faced with a unique challenge.

As Daniel Kelley, assistant director for the Anti-Defamation League's Center for Technology and Society, points out for us, games "straddle two universes" in a way other companies haven't had to.

"On the one hand, games are media," Kelley says. "You can talk about hate and harassment in the same terms you talk about it with movies or TV. Whose stories are being told? Who's being included, who's being excluded?

"At the same time, online games are social platforms. A comic book is not a social platform, so the fandom that exists around it exists on platforms that are not necessarily run by the comics industry. The game industry is creating social spaces. Online games are social spaces, so the responsibility for the form that hate and harassment take in those spaces is the responsibility of the companies that make those games."

That means game companies are having to fight hate on two different fronts, and success on one front doesn't necessarily mean success on the other. Kelley notes that despite some missteps Blizzard has gone out of its way to create an inclusive roster of playable heroes for Overwatch. So from a games-as-media perspective, one might think it's a commendable example of progress for the industry. But according to an ADL survey from last year, the game still has a long way to go in fighting hate from a social platform perspective.

"In our survey, 75% of people who played Overwatch experienced harassment," Kelley says. "So it's unclear to me at this point how efforts to make games more inclusive as media interacts with games as social spaces and the harassment we see in those spaces."

The problem of how social platforms can successfully fight hate is of particular concern to Kelley, who sees much of the industry adopting the tactics of Facebook or Twitter circa 2006, with terms of service and user behavior policies on major games more or less aping the same language as those platforms used to. That's concerning in light of how those platforms went on to shape the world we live in.

"It's important that companies use their public voice in this realm and put on their platform, 'We don't allow hate speech, and here's what we mean by hate speech"

"I don't think you could have predicted at the time that [Twitter and Facebook] would be the centerpiece of the 2016 election, or 2017 would come along and one of these platforms would be implicated in genocide in Myanmar," Kelley says, referring to Myanmar military using the platform to promote ethnic cleansing of the country's Muslim Rohingya minority. "There is a lot the game industry could learn from the past ten years around hate, harassment, and extremism in social media that could be applied to game spaces as they become more social."

While there are still criticisms to levy against Twitter and Facebook for their moderation practices and how they allow people to use their platforms, Kelley says they've made progress. One specific change he welcomed was the switch from the sort of vague terms of service he sees the industry using to a more detailed breakdown of what is acceptable and not on a range of different content.

"I think it's important that companies use their public voice in this realm and put on their platform, 'We don't allow hate speech, and here's what we mean by hate speech,'" Kelley says.

He acknowledges it's still a considerable problem trying to enforce guidelines consistently at the scale those platforms operate, but Kelley said having the games industry should still be looking at such measures as examples.

"There's a lot more they could do, but if they had in place now was in place ten years ago, I think we'd be in a very different place."

As for other measures the games industry could take, he says transparency is a big one.

"If the game industry were able to come together and collectively -- or with selected individual companies to start -- really share data with the public and society about the problem, I think that would be a huge step forward," Kelley says. "But of course to do that, they would need to create a ruleset around policy and enforcement on their platforms in ways that are much more robust than they have now."

When asked how much he feels the industry has bought into the idea that it has a problem with hate and harassment that needs addressing, Kelley says there are definitely good people doing good work on the issue, namechecking the Fair Play Alliance and Roblox as examples.

"How do we not just kick out the worst of the worst, but what is that pathway to radicalization, [or] the pathway to reforming folks in these spaces?"

Roblox and Fair Play Alliance members like Riot Games have embraced the idea that rather than hand down bans for inappropriate player behavior, it's better to try to reform them, typically by incentivizing pro-social behavior through game design.

"This is an area where I feel the game industry has done a lot more thinking than social media," Kelley says. "In the social media world, there isn't this discussion of how do we reform [bad actors]? I think that speaks more to games as a culture versus social media as platforms."

Kelley says social media platforms generally focus on suspensions and bans when it comes to hate and harassment, but he says it's interesting to consider the possibilities of the reform approach.

"If we're building this interactive space, how do we not just kick out the worst of the worst, but what is that pathway to radicalization, [or] the pathway to reforming folks in these spaces? It's a super interesting question," Kelley says. "It requires more research, and it requires more transparency from the game industry to say, 'We tried X and it didn't work. Or it did work, and here's how you can replicate it in your game.'"

Unfortunately, when it comes to the biggest players in the industry putting in a good faith effort and understanding hate and harassment are a barrier to growth, he says not everyone gets it.

"Valve has been actively pushing against this kind of work"

When I ask if any of those big companies have been negligent enough to deserve being singled out, Kelley doesn't hesitate.

"I would say Valve, absolutely. Valve has been actively pushing against this kind of work. At the same time Discord and Twitch were expanding their policies around hate, harassment, and extremism, that was around the same time [Valve] was like, 'We allow anything except for trolling and illegal content.'"

Valve adopted that policy for Steam in mid-2018. It expanded the criteria for what it would not allow the next year when a developer put up a Steam store page for Rape Day, billed as "a game where you can rape and murder during a zombie apocalypse." After backlash, Valve pulled the store page from Steam, saying, "[W]e think 'Rape Day' poses unknown costs and risks and therefore won't be on Steam."

"From my understanding, there are a lot of efforts going on at a lot of companies, but in my mind, [Valve has] the longest way to go," Kelley says.

His comments on Valve aside, Kelley is very clear that his focus is on working with the games industry on finding solutions. He brings up the aforementioned ADL survey again, noting that it also asked about the positive social experiences people had in games.

"In order to acknowledge what are real problems in game spaces, we also have to look at, measure, and account for the fact that these are positive and powerful community spaces for many people," Kelley says. "One of the more interesting results from the survey was that 13% of respondents found a partner in an online game space, whatever that means to them... 51% made friends, 20% learned about themselves. These are not inconsequential experiences people are having. The reason why it's important to address hate and harassment in these spaces is because of the meaningful experiences people can and do have in these spaces, and the need to democratize or make sure that these spaces are available, safe, and inclusive for all people.

"The norms that come up in the qualitative research is that women and people of color go into game spaces and just turn off the mic and don't speak, because they know if they speak, they'll be identified, targeted, and harassed. That's just the reality of how they play. But I think it speaks to the power of games that they do continue to play... The work we're committed to here is changing norms so that everyone has the same chance to have the same deep, social, playful, enriching experiences that folks can have in that environment."