What I learned about community management from my immigrant parents

Kitfox communications director Victoria Tran on how compassion is at the heart of good community management

I don't think my parents immigrated to Canada so that I could have a job that allows people to get angry at me on the internet, but here we are.

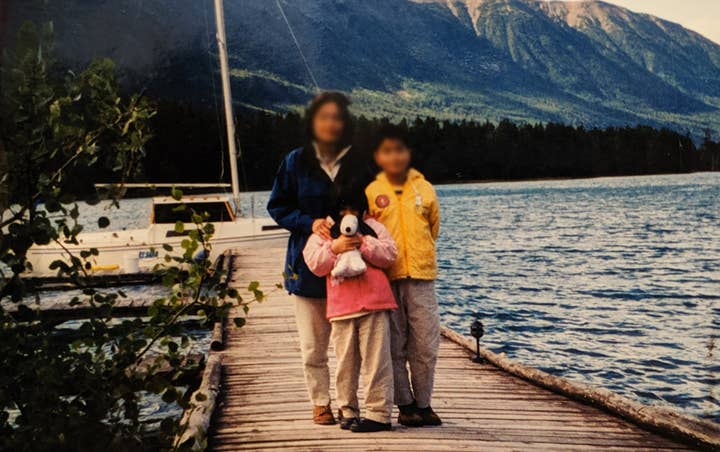

Actually, let's back up for a second for some quick background info. It's a disservice to them to say they immigrated. They fled. They left Vietnam when they were 17 to escape the war. They ended up in Canada penniless, without a college degree, or any knowledge of the English language.

It was hard. There were bribes, actual pirates, death, and disease. My dad lived in a bedroom with six other people -- my mom with four.

The entire thing is a story, but for another time. Ever since I was a kid, they'd regale me with stories of their past, which I could never relate to. But maybe that's where my need to understand and communicate with others started from. So let's talk about how my parents inadvertently prepared me for community management.

1. THE POWER OF LANGUAGE

My parents learned English via context, movies, and their workplaces (as busboys, in a butcher shop, as cashiers) This meant, especially in the mid-twentieth century, they learned some, well, problematic terms.

"Language is hard, people can mess up unknowingly, and they can be given a chance to learn"

It doesn't necessarily mean they hold problematic viewpoints -- more that they didn't know the weight of the terms or possess the tools to explain their feelings another way. When you lose your main language, a lot of nuance and cultural understanding is lost too. For instance -- in English, we use the word "love" for our partners, parents, or friends. But in Vietnamese, "thương" is a steady, understanding love (e.g. parents or married partners), while "yêu" is a strong, passionate love (e.g. new relationships). The all-encompassing word "love" can be a weird, unnatural thing to say if you aren't used to it.

Obviously, just because people use problematic terms without knowing it, doesn't mean they shouldn't be corrected or taught to do better. But it does mean that not everyone is coming from the same place; language is hard, people can mess up unknowingly, and they can be given a chance to learn. As a community developer, my initial inclination is always to see if I can help people learn first.

2. PATIENCE

When I was a kid, I used to lose my temper at my parents a lot. It could've been for any number of reasons: I couldn't understand what they were saying, I was impatient with how long it took them to pick up on English phrases, I hated not being able to do "normal" (Western) kid things.

Often in community management, you'll get frustrated at people. Someone asking a question you've clearly answered in the game description, strange comments on an article, unfounded complaints, etc. But you never know where someone is coming from. Is there a place in your communication that is unclear? What have you been taking for granted as "normal"? Find empathy, and you'll find patience.

3. SIMPLE COMMUNICATION

When I was in elementary school, my parents' English skills were still quite basic. So as a kid, I was the one reading school forms, government documents, and official notices and translating them into simplified English for my parents. The only time they touched the papers was when I asked them for signatures. I learned how to get information across in the easiest way possible.

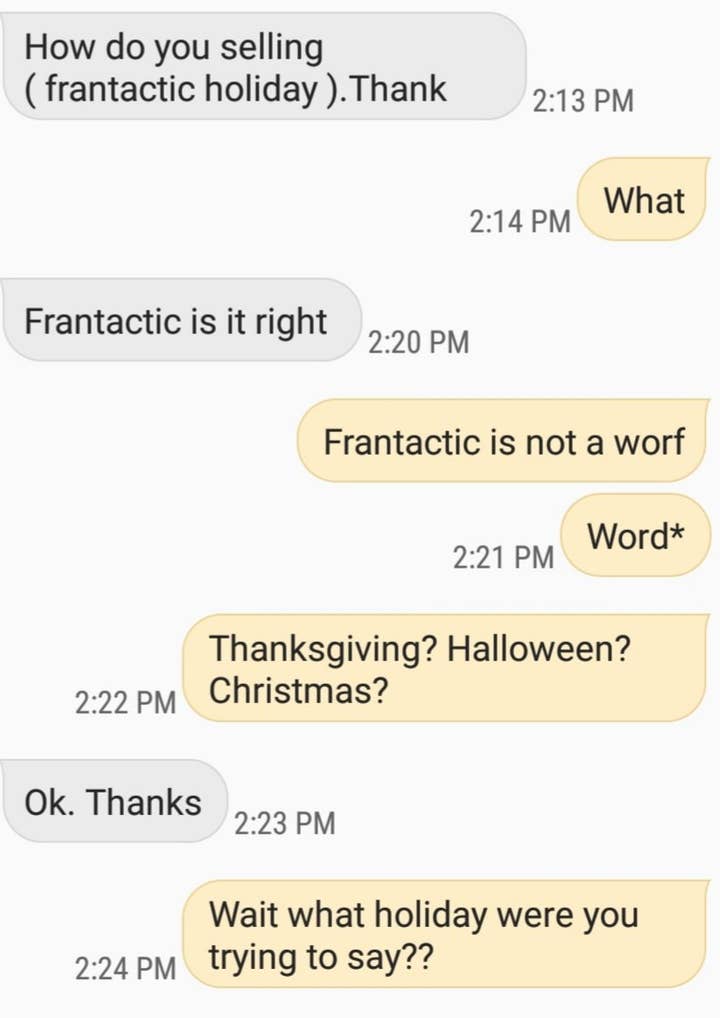

Even now, I still get emails and texts from them asking me to check their work or write something out for them. Sometimes I have to figure out what they're even trying to say.

With communities, especially since we're so globally connected with social media, the best practice is to write rules, news, and marketing beats as simply as possible. Similarly, when you're reprimanding or explaining to someone why they broke the rules, say it in layman's terms. Using unnecessarily haughty language or jargon to prove you know your stuff helps no one.

4. JUDGEMENT

It can be tempting to judge others for sending emails and messages with broken English. Worse, to not take them seriously or mock them (privately or publicly.) Don't do that. Don't let others do that. As a community manager, be the moral high ground. You, as the person enforcing the rules (or even making them!), need to be a role model for how a community behaves.

I've seen people mock my parents for their English. It infuriates me, and it's unfair to them.

5. GRIT

Resilience defines my parents' experiences, especially when it comes to judgement, anger at them, and an unkind world.

But they still worked hard. They worked because they wanted me to be in a place that was better than theirs -- financially, emotionally, physically. They believed things could be better, took every insult hurled at them, and moved on.

"You can't feel all the time, or else you'd have a mental breakdown. But when I have the bandwidth, I try to leave the communities I interact with better off than they were before"

So I can too.

It's easy to fall into the trap of passively banning people, going through the motions, building up walls. And I can't say I blame community managers for that; it's tiring to have insults thrown at you. You can't feel all the time, or else you'd have a mental breakdown. But when I have the bandwidth, I try to leave the communities I interact with better off than they were before.

I don't want to be some neutral presence. I can complain about Twitter being a hellsite. I can complain about gamers being entitled. But what am I going to do about it? Even when the internet seems against me or the studio, how can I work through the situation to leave the future people who interact with us in a better place than before? Or how can I be resilient through a hard time during our game's release to make it so the next game has a better, stronger community waiting for it?

6. LONELINESS

I've always had an odd sense I don't belong anywhere fully. I don't speak enough Vietnamese to be Vietnamese for my family, I can't speak Chinese with my predominantly Chinese-Canadian friends in Vancouver, I don't speak enough French in Quebec, I'm too Vietnamese to be white.

It's a complex loneliness.

But...

Maybe you've felt it too. Not my particular loneliness, but another just as deep and complex as my own. Connecting with others may be messy, imperfect, and full of barriers, but it can still happen.

I understand, and I think that's helped me do what I do.