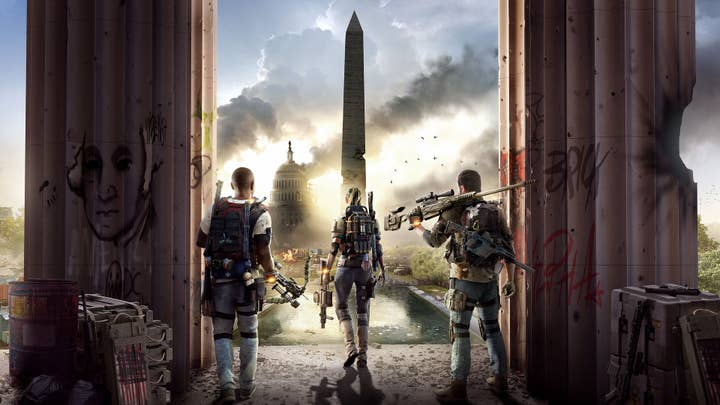

Stop asking "is it political?" It always is | Opinion

Asking developers if their games are "political" has become an exercise in avoiding outrage; there are better ways to explore this complex, important question

I'd like to take a moment this week to make a plea to everyone who writes about developers: please, please, for the love of god, can we all agree to stop asking them whether their games are "political"?

Look, I get it; there was a hell of a lot of grim humour to be had from watching developers who are clearly under the cosh of a tedious publisher edict struggle to throw together some bland inanities about how their game definitely has no political meaning whatsoever. It was the perfect 'gotcha!' question, because everyone in the room knew that the games being discussed had clear political meanings and intentions, but the interviewees weren't allowed to actually say that, so they ended up embarrassing themselves rather often. Hilarious, at least the first, oh, dozen times or so.

"It has reached the point where 'is your game political?' doesn't carry any meaning at all"

The more this question gets used, though, the less meaningful it becomes. It has reached the point where "is your game political?" doesn't actually carry any real meaning at all; it merely leads to a dance of tedious expectations where the developer trots out some platitudes about how non-political everything is, purely to avoid getting screamed at in one ear by Twitter and in the other ear by their publisher's PR person.

Yet in the very same interview, the same developers will often eagerly discuss the real-world, contemporary or historical inspirations for their games, the importance they place on allowing players from different backgrounds to feel welcome and represented, or the powerful themes and messages that they hope will resonate. You know, what you or I might call, oh, the 'politics' of the game.

The latest episode of this silly rhetorical dance is also one of the most bizarre, with the developers of the upcoming Call of Duty instalment -- a game about a geopolitical struggle in which one level has you playing as an actual child soldier -- tying themselves up in intellectual knots in order to find some way to say "no, it's not political" in interviews. Given the content of the game, this is stupid to the point of being downright bizarre -- and the developers know that. They know they're making a game that has a powerful, overtly political point to make. They're smart people, and there's no way they sat around and discussed putting players into the role of a child soldier without understanding that that is intrinsically a political statement.

The problem is that they also know that the word "political" itself has become a rhetorical poison pill; you can do all the politics you like in your themes, your world-building, your gameplay system and your narrative, but as soon as you actually say the cursed words "yes, it's political," that becomes the focal point of everything about your game. They know that failure to do the "it's not political!" song and dance will turn their efforts into a battleground for online cultural conflict, detracting from the game itself -- and no matter how much they as creators may even welcome that, their publisher will have a litter of kittens at the prospect.

"Call of Duty's developers know that failure to do the 'it's not political!' song and dance will turn their efforts into a battleground for online cultural conflict"

It's daft and unfortunate that a word that's so useful and well defined has become so loaded and misunderstood. The demand that creators must "keep politics out of video games" is angrily hurled by a small but loud minority of consumers who either lack the wit to understand that games about war and conflict are inherently political, with the uncritical depiction of the status quo being a strong political stance in itself. Or perhaps who understand that full well, but choose this argument in bad faith because they recognise the rhetorical power inherent in its deceptively simple demand.

Precisely because it's not really a meaningful or logical demand -- and perhaps because often it's not intended in good faith -- it has lost much of its actual meaning and been reduced to a culture war slogan. Hence, if your game "has politics in it" then it's bad; you're instantly labelled as taking a specific stance as an opponent of the angry minority. Hence the 'gotcha!' nature of the question; answer wrong and you're making a political game about war and suffering and conflict and victimhood. You've dared to step beyond the realms of rubbing your erection through your jeans while you contemplate how much you like guns and how cool explosions are, and now you're cog in the machine of the Frankfurt School's Cultural Marxism, and undoubtedly a card-carrying member of the White Genocide Plotting Circle (meetings Tuesdays and Fridays, potluck lunch third Sunday of every month).

Say your game doesn't have politics in it, though, tacitly acknowledging that the word "politics" in this context has been stripped of its actual value and become a hollow emblem of an angry and extremely online cultural struggle, and suddenly you're actually free to discuss what's genuinely important -- themes, ideas, perspectives, the things that a creator wants their players to experience and think about and learn from. A rose by any other name would smell as sweet; if we have to stop using the word "politics" in order to avoid every discussion being swarmed by the internet's significantly less buff answer to the Dothraki hordes, then so be it.

Of course, there's a degree of cowardice here which should not go entirely unacknowledged; it's pretty damned depressing, after all, that we're at a juncture where Wolfenstein's overt proclamation that Nazis are bad and that Nazi collaborators can also go fuck themselves feels like a refreshing blast of honesty, but here we are. Not every game needs to stand on that soapbox in order to have valid and important things to say. Not every creator needs to be willing to put themselves out there on the barricades like MachineGames does.

"'Is it political?' is a snide way to feed an online argument, not a real question"

The tedious inevitability of the interview 'gotcha!' question about politics is making the choice of whether to do that into the beginning and end of a story that's actually much longer and more complex. It isn't just that it's a predictable question that's become rather dull; it also fails to dig into the questions we should really be asking.

Games are a mature medium. It has been deconstructed and reconstructed backwards and forwards, and there is nobody with two brain cells to rub together in a position of creative authority who doesn't understand that war games are intrinsically commenting on war, that violent escapism doesn't also carry a strong message in how it chooses to depict that violence. Game creators are smart people, and their political ideas and their expression are a fascinating topic -- one that will never be captured in a meaningful way by the smug "is it political?" question.

"What does it have to say?" is valid and meaningful. "What does it reflect about our world?" could open a door to a great discussion. "Is it political?" is a snide way to feed an online argument, not a real question.

So that's my plea; stop asking "is it political?" and start asking instead about the actual politics of each game. For all the backlash against "politics in my video games!" in recent years, the move towards engaging with more complex topics in more progressive, thoughtful and interesting ways hasn't actually slowed down. Games are played by, and made by, a more diverse and multicultural group of people than ever, and that's reflected in the stories they tell, the characters they introduce, and the themes they engage with.

It's not always done well, and plenty of incidents demonstrate that the industry is still more than capable of being pretty thoughtless in how it addresses mature and sensitive themes. But we've come a long way from the time when almost every blockbuster game was simply a celebration of how cool violence could look. Let's try to ask questions that reflect more of that progress, rather than fishing for responses that merely dance around the predictable reaction of angry people on the internet.