Could there be a speculative script industry for narrative games?

Falmouth University lecturer and games writer Hannah Wood ponders whether writing can be done upfront for story-driven games

Games writers have historically been treated as what Rhianna Pratchett dubbed 'narrative paramedics', brought in too late for an emergency operation to patch up bad story or stitch together characterisation and dialogue to fit the game design.

It often happened because the more invisible art of story and narrative design was taken on by those who can build games. Only at the point when it was too expensive to fix, the story and gameplay didn't gel, characters had no complexity, or the dialogue was hammy and without subtext, did the skill of creating story world logic, narrative structure and characterisation - expressed in actions, events, mechanics, environments and dialogue - get revealed.

As Dan Abnett said in an interview published on GamesIndustry.biz last week: "It's past time studios got past the idea that story is something anyone can do, that it's something that can be scribbled down on the fly by people whose expertise, often brilliant, lies in other areas. It's like expecting your very skilled plumber or engineer to sort out the electrics for you while he's at it."

Game projects overwhelmingly start with those skilled plumbers or engineers; but, what happens when electricians who also understand the complex wiring, plumbing and engineering of the house, have a game idea? How do they find ways to bring a team together and pay plumbers and engineers?

Sam Barlow is the most obvious example. He told me that he self-financed Her Story because "it felt like something that no publisher would want to fund". The outcome was a critical success that reinvented interactive storytelling, sold 100,000 in the first month and swept the board of narrative and innovation awards in 2015-16. So why isn't there a speculative script industry in games that bets on these kinds of dreams in the way the film industry does?

North by Northwest, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Thelma & Louise, Lethal Weapon, Basic Instinct and The Matrix were all original ideas, not owned or commissioned by a studio and written by out-of-work hopefuls. At Hollywood parties, those writers were looked upon pitifully, like they must be in bad shape to be working on 'an original'. Then Butch Cassidy became 1969's highest grossing movie, a multiple-Oscar winner, and created a new business model: write first, sell later.

Not all spec scripts become successful movies, but they do introduce more diverse content - so could they work in the video game industry? Especially as game engines like Unity and Unreal become more universally accessible and hardware becomes standardised, making experimentation cheaper, increasing interactive design literacy and reducing the production time spent grappling with technology. Does that free up more time to focus on narrative innovation and its value at the start of the process?

"North by Northwest, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Thelma & Louise, Lethal Weapon, Basic Instinct and The Matrix were all original ideas, not owned or commissioned by a studio and written by out-of-work hopefuls"

Technological advances have always impacted narrative possibilities; an early example being increased storage space enabling representation of larger narrative worlds, and aiding the popularity of adventure games in the process. Half-Life 2 was a watershed moment in game narrative, the absence of cutscenes amongst the many innovations that made it so popular. Mods of it (in the form of Dear Esther and The Stanley Parable) then went on to have huge success, inventing the story exploration game/walking sim genre that removed combat mechanics and gave narrative affect primacy over mechanical tasks like shooting and puzzle solving, lowering barriers to entry in the process.

The market for narrative-driven games has only grown; studios recognise that story is a differentiator and narrative isn't just laid over game rules but provides an interwoven set of devices that support and manipulate the actions of gameplay, with every discipline contributing to its delivery and impact. There's still some way to go, and it's a long time since Half-Life 2, but the technical skills required of writers are gaining equal value to other technical disciplines as players demonstrate how much they like story in games, and call it out when it's bad. As a result, writers are more often there at the beginning of the process and integrated with all elements.

Have these changes created the conditions for a business model where writers, or writing teams, fully script an idea that can then be put into production? Especially in a climate where many freelance game writers are based outside studios; and in a context where gamers are calling for more complex characters, and narratives that go beyond hero quest power fantasies, and goal-directed 'entitlement simulators,' to explore the messier and more intimate details of life. As 80 Days writer Meg Jayanth said in her GDC 2016 talk: "Whoever heard of that great novel where the protagonist got exactly what they wanted all the time?"

Games are a different animal to novels, film and theatre, and there are different aesthetic and technical decisions to be made, not least with the current limits of AI heavily impacting on the use of narrative devices. Writers in games need to be collaborative and can't think the script has all the answers; it doesn't in film or theatre either, but what it does offer is a place where new ideas can be experimented with on the cheap.

"Games are a different animal to novels, film and theatre. The current limits of AI are heavily impacting the use of narrative devices"

Academic research has identified how stimulating players with goal-directed mechanical tasks, like shooting and puzzle solving, can stymie empathetic engagement - a cornerstone of narrative impact. This might go some way to explaining the success of story exploration games, where the goal is to assemble narrative, rather than to dominate, solve or win. These games have found ways to traverse the limits of AI, that make it easier to shoot NPCs than have a conversation, and deliver narratives that tackle intimate and everyday human realities. Dear Esther reached profitability in 5.5 hours, Gone Home sold 250,000 copies within six months, Firewatch is on 700,000 in a year and a half, What Remains of Edith Finch has sold 50,000 within two months on Steam, and more on PS4 (these figures are all taken from online sources).

I'm one of a demographic with a hunger for shorter play, story-driven games that pair self-directed gameplay experience with empathetic narrative immersion. I'd rather sit down with one of them and a pizza on a free weekend than watch Netflix. I want to make a business of them too and, in the past few years, developed a script and design for a crime drama video game called Underland.

How do you get a game made as a writer in the wilderness?

In Underland you play an investigative psychologist analysing the evidence to find out why a journalist has been arrested for murder. It's full of sex, drugs and - well - journalism. You are given access to a remote police server housing the case files and asked to find the killer's motive. In the non-linear investigation of the evidence you can choose any path you like to solve two murders. At the climax, there's then a flip in interactive mode and you impact the outcome for the journalist.

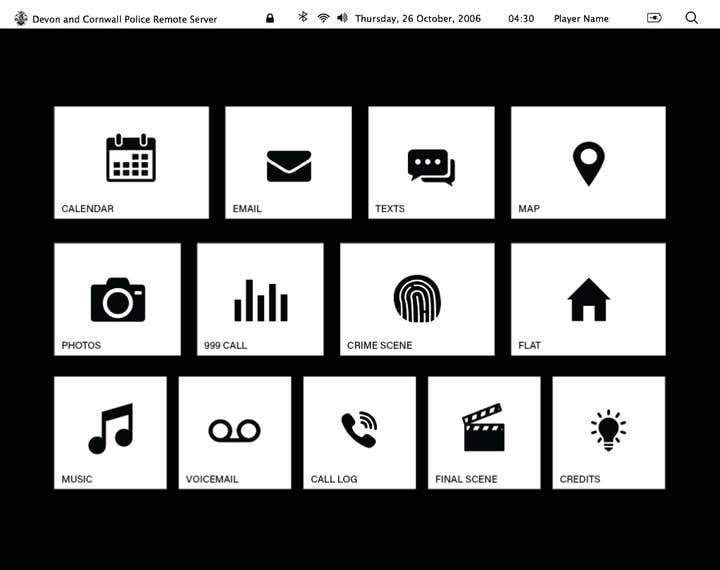

In the script prototype the main interface looks like this:

The crime scene and flat are explorable spaces with some environmental story puzzles; the calendar events are explorable interior and exterior environments - a newsroom, underground club, marina, artist studio, house - with scene bursts embedded that are the memory of events; the other elements - texts, call logs, emails, photos, voicemails are as you would find them on an average computer and tap into our voyeuristic desires, as well as the tensions between our real and digital selves.

The influence and inspiration of Her Story, Gone Home and Everybody's Gone To The Rapture is obvious, but Underland also draws a love of Nordic Noir, thrillers like Silence of the Lambs and crime fiction, as well as two crime story formats based on the premise of wrongful conviction - the podcast Serial and docuseries Making a Murderer; shows which engage audiences in a critical debate about the police case made against individuals. The premise of Underland is similar, in that it asks players to construct the police case from the evidence by interacting with the chains of cause and effect.

"I'm one of a demographic with a hunger for shorter play, story-driven games. I'd rather sit down with one of them and a pizza on a free weekend than watch Netflix"

Like most crime fiction, the main theme is justice, but the game also explores issues around news gathering, ambition, police investigations, the personal impact of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, the effect of childhood on adult identity, sex, love, betrayal and obsession. It also (this is the science bit) does something new with the form in the use of dramatic irony, which is rarely used to generate narrative drive in video games because it works on the basis of an audience knowing more than the character, something hard to achieve when you're playing the protagonist.

Underland isn't a game that could just as easily be a film - the form and content work together to create meaning; its best format is the story exploration game, where narrative and player agency can be negotiated so the mechanics have resonance with the overall theme and the player's experience is paralleled with the central character's story.

As I was writing, I was continually asking how to do it so the experiential narrative of the player's journey could be represented? Unsatisfied with presenting it in a linear document, I used Adobe Muse to build an interactive script prototype. That digital script can be read in the non-linear way it is designed to be experienced so investors and collaborators can see how it works and get a clear sense of how it would feel to play. The prototype is not powered by a game engine so it does not do some of the jobs the final game would (show time passing, mark story assets as seen, offer a search function or gate the final scene, for example), but the script is clearly illustrated to explain how those functions would work so they are easy to imagine.

It's not a prototype in the usual sense of the word in video games, because I didn't have the budget or the visual or programming skills; but it is a complete script wireframe which also uses a markup language based on Henry Jenkins classifications of types of narrative architecture used by game designers. Each story asset is marked up to identify the use of enacted, environmental, embedded or epistolary narrative, making it clear to readers how it would be executed technologically. The emergent narrative obviously isn't scripted as that comes out of play, but the functions of the prototype approximate it.

Underland, as an indie story game, is nowhere near as complicated structurally as some AAA titles but the prototype is the best solution I had to the problems writers TJ Fixman, Marianne Krawczyk and Tom Bissell have reflected on in terms of the lack of a universal writing format for video games in the way there are scriptwriting conventions for films and plays. In the article, they argued that it's one of their biggest obstacles, and requires them to write in a fragmented combination of Final Draft screenplay software, Excel files and other docs, which can make it difficult to track changes and gain a cohesive overview of how the game will work from the written documentation.

"Underland isn't a game that could just as easily be a film - the form and content work together to create meaning. Its best format is the story exploration game"

Video games are now about the equivalent age film was when it got sound so I did some investigation of how film scripts evolved from scene lists to scenarios to continuity scripts to screenplays, and theatre scripts from backstage plots mounted on boards to printable documents. I wondered if the lack of a format contributed to the treatment of writers in the video game industry as 'narrative paramedics' and if there was potential for the conceptualisation of a format that would enable writers to pitch a spec script to a developer or publisher that would provide enough information to put it into production?

In a discussion on the Script Lock podcast, Robin Hunicke made the case that breaking down the millions of pounds spent on one title into smaller chunks, for a wider range of teams, would create more diversity of product. She wasn't talking specifically about writers, but perhaps upfront finance for writers and writing teams to develop playable story ideas to a point where they are ready to go into production might also create more diversity and be more financially efficient? To find out, I sought out the writers and creators I respected and admired to get their perspectives and experiences.

Rhianna Pratchett said she didn't know of a situation where a writer had presented a finished script to a team and they had gone on to make it. She cited Zombies, Run! as writer Naomi Alderman's narrative idea and the only example she knew of where a writer was give that much "power, respect and recognition". That game, by Six to Start and Naomi Alderman, was the most successful video game on Kickstarter in 2011 and exceeded two million sales and downloads in 2015, attracting equal numbers of male and female players through a story with strong characters of both sexes.

Rhianna described the existence of multiple scripts for Tomb Raider and Rise of the Tomb Raider and how in her career she had scripted in a variety of software including Word, Final Draft and Excel. She said that she tended to use the sensibilities of screenplay writing with the addition of noting gameplay triggers to scenes, but that with the Tomb Raider games they found they needed to visually represent the script to communicate to other team members what they were trying to achieve. The GDC panel by the narrative team at Crystal Dynamics on the eight-step process they pioneered to make story the spine of the process is a great exposition of this.

"Sam Barlow believes that giving writers time to develop ideas and present a script would create more diversity but the games industry doesn't understand what writers do beyond words on the page"

Finally, Rhianna also argued that any format would have very different requirements depending on whether the game was a role-play, first-person shooter or real-time strategy and concluded that because the process of game-making was so collaborative and fluid, building up narrative literacy in the industry, embedding writers better in teams and getting every member of a team to support story and understand their part in it would be a better approach and help to overcome disjunctures between narrative and gameplay. She said: "I don't think it's about the tools at all, it's about the people."

Sam Barlow said he believed that giving writers time to develop ideas and present a script would create more diversity but the games industry did not work like that, through a combination of lack of understanding about what writers do "beyond words on the page" and a reluctance to add any more time to what was already a long production cycle.

He said he had spent six months before Silent Hill: Shattered Memories was signed working out the whole game, which proved useful when it came to production because everything could be checked against the very detailed outline. He added that outlines tended to act as the de facto script and a means to budget and plan, and that "you might have people who have an idea for a game but haven't sat down and written it because there is no market for someone saying here's a finished script, it's ready to design."

Dan Pinchbeck said The Chinese Room get pitched scripts often but reply to say that the fun of it is coming up with the ideas. He argued that the best vehicle for conveying the experience of play was a prototype of the game and that there was no replacement for team members talking to one another to marry conception and execution. The studio used a wiki tool called Confluence as an information sharing portal for Everybody's Gone To The Rapture and could view scenes by timeline, location and character. They gave basic scripts with virtually no stage directions to the actors and hired a director to block it out in rehearsals like a theatre play.

Blizzard is a company evolving its script format so they are more user-friendly for actors and therefore likely to produce better narrative outcomes. Other discussions and research revealed that game companies often have their own proprietary software for scripting - Suite at Square Enix, for example.

Fullbright's Karla Zimonja said that the only concatenated script they had for Gone Home was the one that was used for voiceover recording, and Steve Gaynor added that it was simply the audio diary texts in linear form. His Designer's Notebook features a mixture of notes and diagrams that chart the development of the concept. Like The Chinese Room, they are a small indie studio, so the conception and build could be done in tandem. As a result, none of the other text was compiled in a central location.

I also did a host of research into live game and interactive theatre scripts, which I'm more familiar with having written myself and won't go into detail on here. The range of processes and perspectives uncovered left me with doubts over the suitability of a universal format, but a question remained about how writers can move from idea to execution? I took all the insights that were generously shared by game makers into the development of Underland and concluded that the best thing I could do, within my limitations and constraints, was to create an interactive script prototype. What remains is the question of the business model to get it made.

Hannah Wood is a writer and game designer at Story Juice, and a lecturer in creative and games writing at Falmouth University.