Are video games the future of live music?

Travis Scott's concert in Fortnite grabbed the headlines, and suggested a way forward for a music industry hit hard by COVID-19

The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted a lot of industries, but the music industry has been dealt a particularly devastating blow. With bands and artists currently unable to perform live shows, the $50 billion global music industry has lost more than 50% of its revenue. Even when venues are allowed to reopen, social distancing rules mean that many will operate at a very limited capacity. It will be a long time before the music industry is able to fully recover.

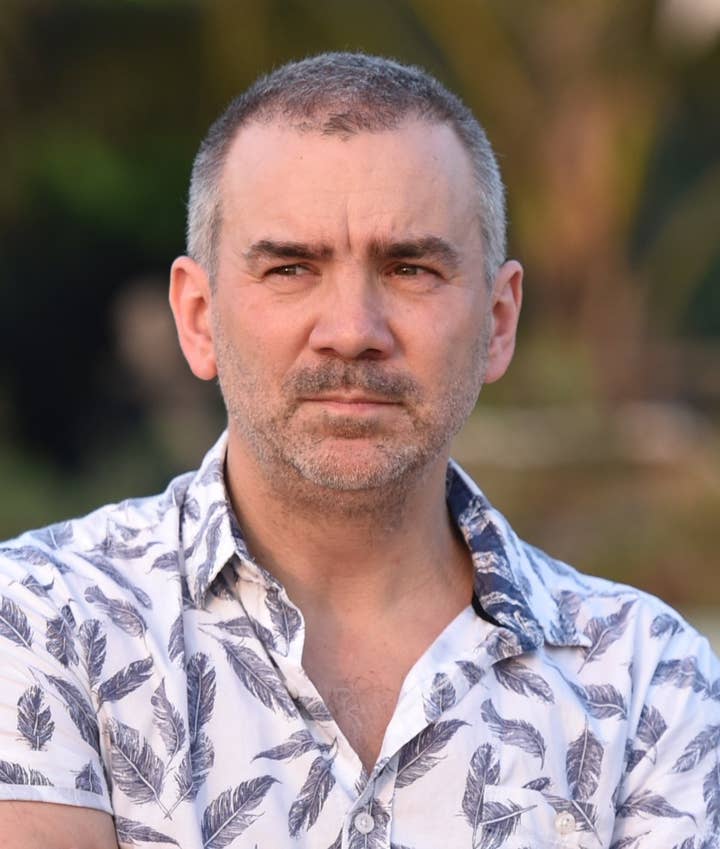

"It's just been an absolute collapse of everything you've ever known," explains live music agent Sol Parker, who represents Billie Eilish, Take That, Liam Payne and many more. He describes the last few months as "armageddon."

"You couldn't have an industry less suited to be around at the same time of the virus. Our entire sector is now being held up by furlough. Come August time, there's an unfortunately reality that's gonna set in and it's gonna affect everyone we know. No one's getting through unscathed and there's gonna be a lot of casualties."

"You couldn't have an industry less suited to be around at the same time of the virus"

Sol Parker

A growing number of musicians are now relying on platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitch to reach their fans, but video games and virtual worlds could provide an additional lifeline in the music industry's biggest battle for survival. Travis Scott's recent performances in Fortnite set a new standard for virtual concerts, and many companies will now be rushing to replicate Epic's endeavour.

Who benefits from virtual concerts?

This isn't the first time a musician has performed in a video game. The release of Second Life in 2003 allowed music labels, promoters and musicians to host concerts in front of virtual crowds, and popularised the idea of virtual concerts. Since then, video games such as World of Tanks, Adventure Quest 3D, The Sims, Fortnite and Minecraft have hosted concerts and even music festivals inside their digital worlds.

But Travis Scott's concert in Fortnite has been the biggest to date. The rapper's deity-like avatar didn't just leave the stage on Sweaty Sands beach shaking; it left the entire music industry shaking, showing the world what's possible when two industry titans collide in astronomical style. His five sets were short and sweet, lasting no longer than ten minutes, but 27.7 million unique players took part, making it Epic Games' most successful in-game event ever. It launched the rapper's newest single, The Scotts, to a number one spot on the Billboard Hot 100 in the same week.

The other stats are equally impressive. The story of the concert was picked up by over 9,000 media outlets -- phenomenal PR for both Epic and Travis Scott. The rapper's social media channels saw a 1.4 million increase in new followers in the seven days that followed. As well as allowing millions of music fans to enjoy a live experience in completely abnormal circumstances, the impact of this tour stretched way beyond what's possible with a traditional show.

One of the biggest benefits for musicians performing in video games -- especially live service games such as Fortnite -- is they're guaranteed to reach millions of people, as long as the game's active audience is large enough. But the concerts in Fortnite raise an accessibility problem. There are plenty of musicians who would love to appear in the game, but there aren't that many similar platforms that support virtual concerts -- at least not yet.

The next few months will be a race to see if a platform can be created that's profitable and accessible to musicians of all sizes.

Building on existing formats

As Philadelphia-based band Courier Club were watching the coronavirus pandemic spread across the world in February and March, they joked that if their upcoming tour was going to be cancelled, they'd just play gigs in Minecraft instead.

"It very quickly turned into reality," explains Michael Silverglade, the band's bassist. "We texted Stephen [Michael's brother], who is a longtime Minecraft player and has hosted servers before. We just started working on it and it snowballed from there."

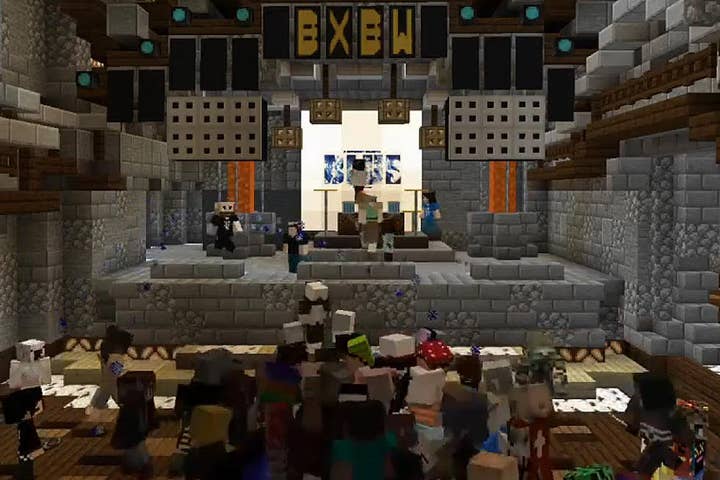

What started as a joke led to the creation of Block by Blockwest, a virtual music festival inside Minecraft. Nearly 30 bands performed across three stages (servers), with 5,000 players stage-diving and jumping around in mosh pits from the comfort of their bedrooms. Bands performed in front of custom backdrops, and square-faced roadies rushed onto the stage to fix minor audio issues.

To take part, bands were asked to pre-record or submit live audio that could be streamed into the game as their avatars performed. The event was a success, streamed by 134,000 players with an NME review calling it "the closest we've come to an authentic online festival experience."

Silverglade says the band couldn't have done it without the technical support of Digital Ocean and Cloudflare, two web infrastructure companies that supported them with server space. The festival was originally meant to take place in April, with Massive Attack set to headline, but it had to be rearranged as a crowd of over 100,000 players crashed the servers before the festival had properly started. Following the success of May's rescheduled event -- which raised $7,600 for the CDC Emergency Response Fund -- guitarist Ryan Conway says the band is currently talking to developers and companies that can help pivot to a model that's more profitable for artists, so they can do it all over again.

"Using virtual events spaces as a gathering point, I think there's a market for that"

Ryan Conway

"If we host enough of these over and over, we can create a sustainable income model for artists that are completely screwed right now," he explains. "We would then subsidize the artists' pay with sponsorships that go in our ad breaks in between sets."

Conway also believes that this type of model can help bands save money. Festival appearances can sometimes cost thousands in travel expenses; a virtual festival appearance would be much cheaper, and potentially more beneficial in terms of the numbers that can be reached online.

"This can provide a cheaper opportunity for artists and their fans to all come together," Conway continues. "Whether that's in [Minecraft] in particular, or Fortnite, or whatever new games are coming up -- it doesn't really matter. Using virtual events spaces as a gathering point, I think there's a market for that."

Virtual spaces as gathering points

Wave, formerly known as TheWaveVR, thinks so too. The company, founded almost five years ago, is the world's first multichannel virtual entertainment platform for musicians. Unlike the Fortnite event, which was pre-recorded, most of Wave's concerts are live and interactive. Artists' body and facial movements are tracked using motion capture technology while they perform in real life. Developers can then edit avatars while the musicians are performing. Rapper and songwriter T-Pain was transformed into a giant fire-breathing demon, while violinist Lyndsey Stirling traversed lush green plains and cyberpunk cities as she performed in front of 400,000 people.

These live performances provide an opportunity for musicians to directly interact with their fans, who can also socialise with each other. As anyone who has watched a Twitch stream will know, this interactive element is an important way for content creators and musicians to build relationships with their communities, which ultimately keeps them coming back for more. Live performances allow fans to call out to their crowds in real time, just like an actual performance, making every event unique.

"The interactive medium, the virtual medium, is the future of music -- hands down," says Adam Arrigo, CEO and founder of Wave, who previously worked at Harmonix as a designer. "We kinda think of ourselves like a virtual Live Nation or AEG, only instead of physical venues, we're actually integrating our technology in building lots of venues inside both video games and these streaming platforms.

"If you look at games like Guitar Hero and Rock Band, and look at how casual and social the interactive medium has become -- the fact that people are treating games like Minecraft, Fortnite and even League of Legends as these social spaces. They're playing games, but they're chatting with their friends and they're hanging out. This is where culture's happening now."

Wave's performances -- known as "waves" -- are recorded, which means they can be rebroadcast into different territories. These rebroadcasts can be customized and edited with additional audio and animation to make them bespoke for certain regions, attracting different sponsors and creating additional revenue streams as a result. Wave also supports the sale of virtual merchandise, and musicians are given a cut of every merch transaction.

"We've been steadily building the tech, relationships, partnerships and teams to build a platform that has the potential to create a ton of value for an industry that right now, really, really needs it."

Will virtual concerts ever replace physical concerts?

While virtual concerts may be an accessible way of allowing some performers to reach millions of new listeners, Sol Parker insists that nothing will ever replace the demand for physical concerts.

"I fundamentally do not think anything can recreate or replicate being in the same room as someone -- I think musicians just make magic," he says. "My prediction... is I think there will be a lot more of it around. It will become a lot more prevalent because of the platforms that are emerging now."

Parker also acknowledges that, for some musicians, dragging their fans into new digital environments may be challenging: "It's very tough to drag an audience to somewhere they're not used to inhabiting, even for bigger acts. There's bigger acts with millions of fans and you would assume that millions might watch them online, but the numbers never add up."

"The interactive medium, the virtual medium, is the future of music -- hands down"

Adam Arrigo

For most bands, the touring experience is also a significant contributor to their revenue. Matt West, guitarist for pop-punk band Neck Deep, says that at least 80% of revenue comes from touring and the associated revenue streams. "In terms of our income," he says, "it's [touring] the main way we get paid."

Bands get a guarantee (guaranteed sum of money) every tour date, but as they get bigger, so do their performances. This requires sound engineers, lighting engineers, drum techs and guitar techs to become part of the touring crew, which are paid by the band. There's also transport to pay for, which means merchandise sales are an incredibly important revenue stream for bands on tour.

In-game transactions are a huge revenue stream for video games, and if digital merchandise can be incorporated within virtual concert models, bands could stand to make a lot of money. Music fans love merchandise that helps memorialise an experience. If Travis Scott wasn't already a household name before the Fortnite concert, the NERF guns, t-shirts and in-game cosmetic items have made sure he is now.

West says it could be a number of years before touring schedules normalise due to the waiting lists that most venues currently have in place. Until then, West and other band members have been streaming themselves playing video games on Twitch, and doing Q&As to maintain interaction with their fans. Neck Deep regularly packs venues with between 10,000 and 15,000 fans on an average tour date, but West says more platforms are needed to support bands of his size.

"I would love for us to be able to do something like that [Fortnite], but I feel like the entry point to do something like that is you have to be huge" he says. "It just seems like an impossible feat to even be considered for because every artist listed there is just beyond massive."

The future of virtual concerts

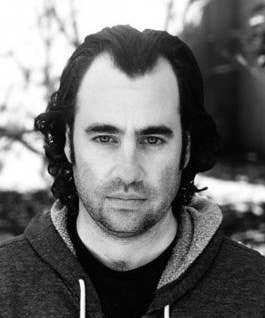

In order to make virtual concerts accessible to everyone, technical issues such as latency will need to be addressed. Matt Squire, a multi-platinum record producer, is currently working on software that enables remote recording in his studio. He believes similar software could be adopted within video game platforms for live streaming audio, and that virtual concerts should always prioritize live audio over pre-recorded performances.

"There's an energy to live music where it feels like the musicians are almost worried," he says. "It's like they're going to mess up, or the sound is going to cut out -- there's so much nervous energy. And I think when audiences feel it, something unbelieve happens. There's a kinetic connection -- nothing that we could ever put our finger on -- that happens when artists play in front of us."

The rush to create the future of live music is now on. According to an interview in The Financial Times, Sony's chief executive Kenichiro Yoshida sent a message to his employees shortly after Travis Scott's appearance in Fortnite, pointing out this could be the group's next big opportunity. A number of job opportunities were spotted by MBW at the beginning of May, with a job listing for an Unreal Engine Networking Engineer stating the successful candidate "will develop and maintain online multiplayer services for immersive music experiences."

EA, a company that's no stranger to the commercial power of music within video games, says it has plans of its own, too. Virtual concerts would be a natural fit for existing EA titles such as Madden NFL if they could be incorporated as halftime shows.

"The Travis Scott/Fortnite numbers were certainly eye opening, and clearly there will be plenty of games and artists now attempting to follow that example," says Steve Schnur, worldwide executive and president of Music at EA. "But how does this idea not just replicate itself, but expand and evolve instead?

"The pandemic has lit a huge fire under the complacency of promoters and agencies, many of which went -- literally overnight -- from some of the biggest numbers in the industry to a dire realization of their own fragility. And when agents and promoters continue to dismiss virtual concerts as lacking the energy of live performance, they're missing the most important point: next-gen music fans -- the very ones they spend every day trying to reach -- have moved past the live entertainment model.

"The lack of that live interaction is not a problem with them, as they're already perfectly comfortable with virtual experiences. These next-gen fans are now awaiting the next step in the medium. And EA has some major developments coming."

Video games have been an important platform for discovering and consuming music since the early 1990s, and there's an entire generation of players that owe their music tastes to games such as FIFA, Tony Hawk's Pro Skater and Grand Theft Auto. In recent years, games such as Rez Infinite, Tetris Effect, Sayonara Wild Hearts, Dreams and Beat Saber have let players not just consume music, but interact and play with it too. Virtual concerts are the next logical step in the relationship between video games and music, and both bands and game developers are eager to tap into the new opportunity that will be created as a result.