#1ReasonToBe: "Listen to the people you do not hear, because they're not allowed to speak"

Rami Ismail's GDC panel explored development in Madagascar, the Philippines, Colombia and beyond

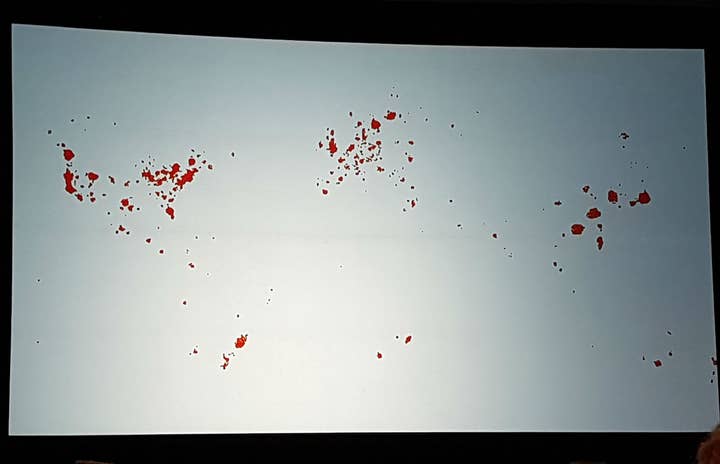

There is a map in the north hall of the Moscone Centre, which invited every attendee of GDC to place a pin in the location from which they worked. The intention was honourable enough; to illustrate the global spread of the games industry, and to position the Game Developers Conference as its focal point.

The result, however, was very different, and Vlambeer's Rami Ismail used a version of the image it created to open his annual #1ReasonToBe panel. With the black lines tracing the coasts and borders of the world's countries taken away, what was left didn't look like much of anything at all.

"It's supposed to be a map of the world," he said, "but it's actually a vague outline of the US, a little blob of Europe, some spots of China and Japan, and maybe a little bit in the far south of America. Apparently, that's supposed to be where people make games.

"The reality is that's not where people make games, because that map would show you a much better picture of the world. This map is the map of people who can come to GDC; who can afford to come to GDC, and who are allowed to come to GDC."

Anyone who follows Ismail on Twitter will already know the difficulties he faced in assembling this year's panel. Out of six chosen speakers, three were denied the visas they needed to accept Ismail's offer of a fully subsided trip to GDC. Out of three backup speakers, a further two were rejected. And one of the two developers he found to replace them was turned away. The Trump administration's explicit travel ban may not still be in place, Ismail said, but its ripple effect is still keenly felt.

Ismail has been working with developers with difficulties obtaining US visas for shows like GDC, PAX and others for several years, and the numbers are climbing rapidly. In 2016 he worked with four people; in 2017 it was eleven; this year has brought 28 cases so far, and it's not even April. The reasons given for these denials - when they're given at all - are myriad, and Ismail asked the audience to consider how many would apply to their own lives.

"This map is the map of people who can come to GDC; who can afford to come to GDC, and who are allowed to come to GDC"

Rami Ismail

"How many of you here got married in the last year, or otherwise had a change of first or last name? How many of you do not own a house? How many of you have a criminal record, or have used any form of drugs in your lifetime? How many of you are independent, entrepreneurs, or otherwise do not have a stable job?

"How many of you are here on a grant, or are otherwise financially supported for being here? How many of you are not married or engaged? How many of you do not have children? How many of you are nervous in interviews or interrogations, or have never been in an interrogation but think you might get nervous? How many of you have ever made a typo on an official government form?"

When Ismail asked those who identified with any one of those criteria to raise their hand, every single arm in the packed room was aloft. Every person in the audience, Ismail said, had fulfilled a reason for being refused entry into the US.

What the six people who could have been on the #1reasontobe panel lost is far from trivial: flights, accommodation and passes to an expensive event in an expensive city, where the most influential people in the games business congregate every year. The potential ramifications could be life-changing, and yet they were left with only, "crushing disappointment, as some informal letter tells them that it isn't happening."

"These developers had stories and passions and perspectives that are worth sharing on this stage, that they will not get to tell," Ismail continued. "They would have opportunities to speak to press, to meet their peers, to forge friendships, chase opportunities, that they will now not get to have.

"Instead, what they got was a permanent mark on their record that will require them to admit they had a visa rejection every time they apply in the future. And I can tell you that that mark does not increase your chances of getting a visa to the US."

The benefit of even a single trip to a place like San Francisco was demonstrated by Carlos Rocha, who makes games with two companies, Below the Game and Syck, in the city of Bucaramanga, Colombia. After finding few opportunities for growth or even stability in his native country, Rocha was invited to the US because of a game called Palabras de Independencia, which told the story of Colombia regaining its independence.

The game, and the opportunity to travel to San Francisco it brought, "saved my company," he said. Although the investor that first invited him was unable to work with the project, the trip brought him into contact with Zachtronics Zach Barth, who initiated a series of meetings that led to a publishing deal with a US company. This year, Rocha will release two games: Haimrik, which was nominated for an award at SXSW, and Cristales, which won five awards at Game Connection only last week.

"I also create games to help others from Bucaramanga, from my city, so I've tried to take a lot of interesting people there," he said. For Rocha, his own success is about motivating young people to, "change the industry from the place we live in."

A similar message was offered by Samer Abbas, the co-founder of Play 3arabi, a mobile publisher that specialises in localising games for the MENA region. Abbas was born in Kuwait, but identified as Muslim, as Jordanian, as Palestinian. He also idenitified as a gamer, who wanted to be a designer from the moment he first played a Super Mario World at the age of 13.

"I was in a region plagued by wars, by poverty, poor education, many problems. I felt I had to contribute something meaningful"

Samer Abbas, Play 3arabi

"People like Miyamoto and the late Gunpei Yokoi were legends to me, for bringing so much joy to so many people," he said. "But I was in a region plagued by wars, by poverty, poor education, many problems. I felt I had to contribute something meaningful, and entertainment didn't seem like an appropriate choice."

Abbas changed his mind during the final year of a course in engineering, when a piece of interactive education software helped him to understand "complex engineering concepts very easily. From this, I realised how powerful interactivity and games can be, and how together they can be much more than entertainment... I decided to try and make a difference in the region. I got my calling."

Abbas has since worked in many areas, but an obvious source of pride is Game Zanga, a game jam that has provided a creative outlet for Arabic developers at a difficult time. "In 2012, at the height of the Arab Spring, the community voted for the theme 'Freedom'. In 2013, when things looked bad the theme was 'Lost'," Abbas said. "380 Arabic games came into existence over Zanga weekends... I was organising it, and I'm proud of that."

Lara Noujaim's home country of Lebanon has also felt the effects of unrest in countries around the Middle-East, due to sharing borders with Syria, Israel and Palestine. "Geopolitically speaking, we are not in the most stable of locations," she said, chuckling. "This has translated to a situation of instability for my country."

Gaming played an important role for young people in difficult times, when, "war broke out and you had to stay indoors, and after everything settled it was a way to put everything behind us and just breathe." And yet, despite the Cedar Revolution happening 13 years ago, the negative perception of Lebanon persists. Noujaim showed a still from the US television series Homeland, which depicted a truck full of armed men, their faces wrapped in scarves, jumping from the back of a military vehicle in a muddy, downtrodden urban area.

"Homeland says that this is what the Hamra neighbourhood in Beirut looks like," Noujaim added. "After seeing this picture - a truck filled with armed men, patrolling the street - who in their right mind would want to go to Lebanon? After seeing this, this is what people think Hamra looks like."

But this is what Hamra looks like; a bustling neighbourhood filled with bars, restaurants, and a centre of tourism in Beirut:

"Today, we appear to be really divided, and I'm not just talking about the MIddle-East; I'm talking all over the world. I really believe that it is crucial, more than ever, to have a language that connects individuals from all over the world. I truly believe that that language is gaming."

Noujaim acknowledged that the Lebanese industry started late, but not nearly as late as the fledgling development scene in Madagascar. Indeed, Matthieu Rabehaja founded Lomay Games in 2015, with the express aim of releasing the first game to ever come out of the island nation. In doing so, he created its national industry at a stroke.

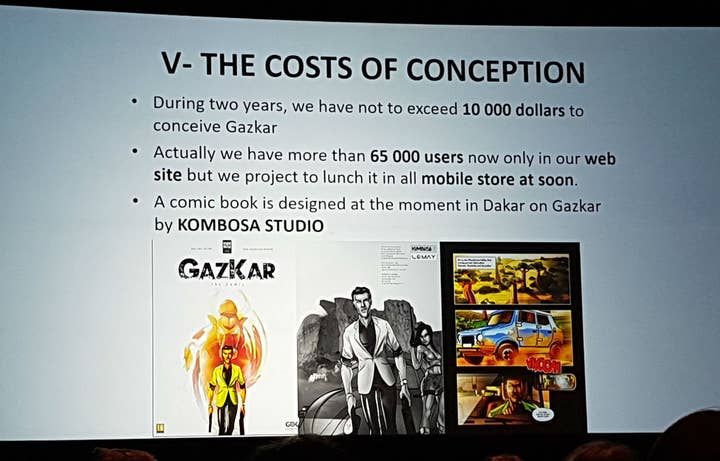

That game, the racing title GazKar, was made by a team of eight people over two years, at a cost of just under $10,000 - most people in Madagascar, he pointed out, live on $3 a day. When it is released this year, the sequel, GazKar 2, will be the second game to ever be released by a developer in Madagascar, and Lomay's next project will be even more ambitious: Dahalo, an Unreal Engine 4 open-world game that will tell the story of the country's history.

"In two years we have been able to solve some problems in the video game industry in our country, and we hope we can achieve our dream to make video games our job," Rabehaja said. "Much remains to be done, but we are very positive because people are becoming more and more interested in the sector."

Rabehaja grew up playing games on the PolyStation, a local knock-off of the popular (and expensive) Sony PlayStation. Javi Almirante was in a similar position in the Philippines, discovering Nintendo games through less than legal channels. "I grew up on Nintendo games," he said. "After school and on the weekends, I was super excited to play them on my favourite console: ZFSNES 1.42 for Windows."

Almirante's line got a big laugh - the biggest of the night - but it also tells a truth of just how global games were long before the mobile market supposedly opened up countries like the Philippines. The players were there, but they operated in grey and black markets. Indeed, Almirante said he was in grade school before he was aware that legitimate games even existed, and the greatest shock was not that they were available, but just how much publisher's expected people to pay.

"Today, we appear to be really divided, and I'm not just talking about the MIddle-East"

Lara Noujaim, Game Cooks

In the Philippines today, Almirante said, there have typically been three options available to aspiring game developers: leave the country, set up a virtual studio, or offer services to international companies seeking to outsource work on AAA games.

"It blew my mind when I found out that one of our studios, Secret 6 Games, was working on Uncharted 3," Almirante said. "But while these solutions might seem harmless, they aren't without drawbacks; because we outsource, a lot of the money that could be going to us is actually going to foreign companies. This reinforces our colonial mentality, where we think that local things are sub-par, and can't be as good as foreign ones."

The situation is starting to change, Almirante said, thanks to a wave of developers who are keen to stay independent and find a voice that is unique to the Philippines. That community has been built on the work of people like Gwen Foster, the speaker Rami Ismail initially invited to speak on the panel - one of those who was denied a visa. In one of his slides, Almirante paid moving tribute to Foster, a person to whom he believed he owed his entire career.

"My very own fairy godmother, Gwen Foster," he said. "Gwen has done so many things for our industry that she deserves this slide... Without her, the Philippine industry would not be where it is today."

But in Trump's United States, it seems almost impossible to know what's required to be a participant in an industry that takes such pride in its global reach. In Foster's case, even being a pillar of an entire country's development community is no longer enough - not any more.

"The language of games is supposed to be universal, but for most people around the world, the world itself is not accessible," Ismail said in conclusion. "So I want to thank you for listening to those that you heard here today, but I wanted to ask you throughout the next year, and throughout your life, to listen to the people you do not hear, because they are not allowed to speak."