The legend of The Legend of Zelda

To mark its 35th anniversary, we look back at the impact of the NES original and how the series has influenced other games

You might not know it from Nintendo's social media or marketing, but Sunday, February 21 was the 35th anniversary of The Legend of Zelda.

To this day, it stands as one of Nintendo's most classic NES titles and spawn one of the platform holder's acclaimed franchises to date. In fact, 1998's N64 outing Ocarina of Time remains the highest-rated game of all time on Metacritic.

But, just as Link's sprawling adventures are often winding tales beset by setbacks and moments of triumph, the series itself has followed suit, inspiring other developers at times and losing its way at others.

The legend begins

Developed as the opposite of Super Mario Bros., which led you on a linear path from left to right, the original Zelda gave NES owners an open world they could explore at will from the very beginning, offering a level of freedom rarely seen prior to 1986.

"The first Zelda was incredibly bold in terms of how much it allowed players to go on an adventure," says Mark Brown, creator of game design analysis series Game Maker's Toolkit and its Zelda-inspired spin-off Boss Keys.

"It didn't try to hold your hand or put you on a linear pathway. It dropped you into this open world and asked you to explore. You could even miss getting the sword at the very beginning if you weren't careful."

Raul Rubio, CEO of Rime developer Tequila Works, adds that Zelda made the adventure and RPG genres -- then typified by myriad stats, passages of text, and lengthy menus -- more accessible to gamers of all ages.

"Zelda bet on a fairytale for its narrative, pure core gameplay, simplicity, and accessibility," he says. "It made you forget about beating enemies and embrace back that childhood spirit of exploration and wonder. In many ways, it has inspired generations of developers to achieve that simplicity, which is no small feat."

"The first Zelda was incredibly bold in terms of how much it allowed players to go on an adventure"

Mark Brown, Game Maker's Toolkit

The throughline of adventure and exploration can be found throughout the series, Brown adds, although this changed as the games became more narrative-driven from A Link to the Past onwards.

"In the oldest games, you truly were going on an adventure because you just didn't know where you were going and had to figure stuff out," he says. "Over time, the series changed from going on an adventure to being told you're on an adventure."

Ishaan Sahdev -- journalist and a person who literally wrote the book on the Zelda series -- agrees, noting that the series' popularity has actually declined as it "strayed further and further from that original design principle."

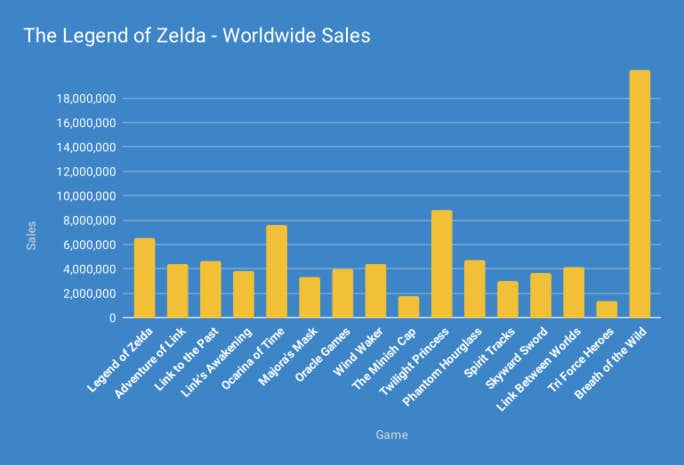

This can be best proven with the series' sales figures. According to Sahdev's research -- factoring in official Nintendo figures and data from a 2020 white paper by Japanese trade body CESA -- only four Zelda games have passed five million sales to date: the original NES outing (6.5 million), Ocarina of Time (7.6 million), Twilight Princess (8.85 million) and Breath of the Wild (21.45 million).

According to Sahdev, there are three common factors shared by Ocarina, Twilight, and BOTW: realistically proportioned characters, a larger game world to explore, and the ability to explore on horseback (which conveys the sense of being on a grand adventure).

"Every single time they've strayed away from these three things, the sales have dipped," he says. "People want Zelda to be an exploratory game that lets them do whatever they want, and it took Nintendo a while to figure that out."

"Zelda's dungeon design is something every level designer learns by heart - including the Water Temple in Ocarina of Time"

Raul Rubio, Tequila Works

Each dip has a story behind it, as Sahdev's book explores. For Majora's Mask, it was rushed development, attempting to build a sequel to Ocarina of Time in half the time. For Wind Waker, it was the cartoon art style that was poorly received by many fans. As Sahdev tells us, every new outing was an attempt to reinvent the wheel until Nintendo's Eiji Aonuma, one of the longest running decision-makers for the series, decided to focus more on what fans expected with Twilight Princess. The result was a new high for the series in terms of sales.

"You don't get to Breath of the Wild without Twilight Princess," Sahdev adds. "Aonuma actually said that when he was doing press for Breath of the Wild. A lot of the ideas in that game were things they really wanted to do in Twilight Princess and just couldn't."

Rubio argues that this process of iteration and reinvention is actually a strength of the series, pointing to Zelda as a "masterclass in game design 35 years in the running."

"Each new entry in the series builds on the shoulders of its predecessors, adding something new to stand out," he continues. "That's why you cannot just copy Breath of the Wild: it's not the interconnection of elemental mechanics, or the approach to open world [design], or the stamina-based climbing -- all that has been done before, but the combination is just flawless."

The next entry after Twilight Princess, Skyward Sword, best illustrated the limitations the Zelda franchise faces: the audience is primarily comprised of hardcore gamers and Nintendo enthusiasts. Skyward Sword was Nintendo's most overt attempt at trying to sell to the broader audience it attracted with the Wii by removing the overworld, creating a more linear journey, and focusing on motion control gestures already employed in the Wii Sports titles.

"Nintendo was under the impression that they were going to sell Skyward Sword to this whole other audience that was never going to turn up," Sahdev says. "That's just the wrong approach for Zelda."

Sahdev observes Skyward Sword was also the Zelda game most obviously designed around Japanese sensibilities -- despite the fact the series has historically sold more in the US. It's the same design principle behind Mario Galaxy's spherical planets: preventing the player from getting lost. Nintendo's former president, the late Satoru Iwata, even discussed how players' dislike for getting lost influenced the direction of the Mario games at the time, and a similar approach was taken to Zelda.

Skyward Sword may have a second chance at beating its 3.67 million sales when it arrives on Switch this July -- the closest activity Nintendo has come to acknowledging the franchise's anniversary so far, although it was not specifically connected to the 35-year milestone in last week's Nintendo Direct.

The series eventually returned to that original design principle in Breath of the Wild, by far the biggest selling entry to date. The game succeeded in striking a balance the series has struggled with since A Link To The Past: story versus freedom. The more freedom you give the player, the easier it is to break the story, and that clashes when trying to tell the tales seen in later entries like Twilight Princess and Skyward Sword.

"That's a concession they had to make with Breath of the Wild," says Brown. "There isn't that strong of a story, it's all pieces of the past you piece together. Nothing particularly happens in the present -- you just wake up and go fight Ganon, and random events happen in between.

"Those two things -- exploration and story -- pull in different directions and are very hard to bring together. There are fervent Zelda fans who don't like Breath of the Wild because it doesn't have as much story."

"Nintendo were trying to sell Skyward Sword to an audience that was never going to turn up. That's just the wrong approach for Zelda"

Ishaan Sahdev, journalist

Sahdev also observes that the series has been a great "incubator of talent" for Nintendo, pointing to key examples throughout the series history. Nintendo legend Shigeru Miyamoto moved Aonuma over to the Zelda team after his first game, Marvelous: Another Treasure Island -- an first-party title inspired by A Link To The Past. Aonuma went on to lead the Zelda series as Miyamoto focused on other projects.

Elsewhere, development on A Link To The Past saw the introduction of Kensuke Tanabe, who became producer of Metroid Prime, and Yoshiaki Koizumi, who went on to produce the Mario Galaxy and 3D Land/World titles. Even external talent has been identified via Zelda: Hidemaro Fujibayashi was director of Capcom-developed entries Oracle of Ages/Seasons and The Minish Cap. His work impressed Nintendo enough to bring him in, with Fujibayashi eventually directing Breath of the Wild.

Links to the past

While Zelda may not have drawn in tens of millions of players until Breath of the Wild, Mark Brown observes that it is a firm favourite among game developers. He notes that Ico and The Last Guardian director Fumito Ueda and Dark Souls director Hidetaka Miyazaki have both pointed to Zelda games as a key source of inspiration. Similarly, while the Castlevania series owes much to Metroid, series producer Koji Igarashi has spoken before about the influence Zelda -- particularly A Link To The Past -- had on his work.

Zelda's influence can be seen in other games throughout the decades, from the Darksiders series to Capcom's Okami. More recent titles also carry a flavour of classic Zelda games -- most people who visited Alfheim in 2018's God of War will agree it felt much like a Zelda dungeon.

Even indie titles seem to draw inspiration from Nintendo's iconic adventure games. Tequila Works' Rime initially drew comparisons with Wind Waker due to its visual style, although Rubio points out the render and visual directions were actually very different. However, he does note that the game was originally designed with a Zelda-style gadget-based progression, with new tools opening new areas. Introducing these mechanics in an eight-hour game felt rushed and the system was discarded, but the spirit of Zelda remained.

"Rime recreated that childhood spirit of exploration and discovery, of awe and wonder, of enjoying wandering the world and not suffering it," says Rubio. "Discovering entire pocket worlds -- or dungeons -- that expand your view and understanding of such a universe. The physical approach to puzzles where interaction and navigation are essential, and the 'aha!' moment... The inspiration, of course, came from Zelda.

"Breath of the Wild is their template for the foreseeable future, so the pressure is on to make a game that sells another 20m units"

Ishaan Sahdev, journalist

" And Zelda's dungeon design is something every level designer learns by heart -- including the Water Temple in Ocarina of Time."

Of course, there are titles more obviously inspired by Zelda. Ittle Dew developer Ludosity openly describes its RPG as a direct homage to the series, although the sequel takes the series in its own direction. According to CEO Joel Nyström, the original Ittle Dew aimed to streamline the "more tedious interactions" the Zelda series introduced from Ocarina onwards, like opening chests.

"The Zelda series went a little downhill UX-wise when it entered the 3D era and didn't really recover until Breath of the Wild, when they started getting back into more snappy interactions again," he says. "[But] the games were always great anyway -- clunky UX didn't really stand in the way of that. [It taught] me the importance of world building and atmosphere, which can sometimes overcome clumsy game systems."

Similarly, Ocean's Heart by indie Max Mraz was inspired directly by his enjoyment of Link's Awakening and the feeling of exploration it gave him.

"But you can only play a game for the first time once," he says. "So chasing that feeling is one thing that's drawn me to game design. Ocean's Heart is my first game, so I wanted to stick to the basics. I knew the design trends of Zelda games work well, because I keep coming back to them over and over and I'm not sick of them."

Mraz adds that another lesson developers can take from Zelda is that games can always be made to be "much weirder." While the bulk of the series is built on established fantasy tropes, it's made all the more distinct by quirks like rocks that tell the time when hit by a sword or inadvertently getting engaged to a fish princess.

"Even Zelda's take on the 'it was all a dream' trope is that you were in someone else's dream, and that someone else was a giant whale god," says Mraz. "I aspire to produce such viscerally bizarre ideas."

Finally, the million-selling Oceanhorn: Monster of Uncharted Seas is perhaps one of the most famous indie Zelda-likes. Like others, developer Cornfox & Bros cites Zelda's focus on exploration as a key inspiration, but also the use of items and the new abilities they unlock as 'keys.'

"In the '80s being able to travel back to certain parts of the world or even the same level was unheard of, and Zelda allowed just that," says creative director Heikki Repo. "Of course, there had been other RPGs, especially on the PC side, but Zelda managed to pinpoint that feeling of offering a real-world to inhabit like nothing else.

"When you put that together with the way items have worked in the series, opening up areas of the world that you couldn't previously visit -- all these design decisions enabled that sense of adventure that was so inspiring to us."

And, as of 2017, the series has inspired the development world in new ways, thanks to its latest entry.

The hero's path

Breath of the Wild took the world by storm. It's the second most acclaimed game in the series, losing out only to Ocarina of Time, and its 21.45 million sales (and counting) are more than twice the series' previous best-seller, Twilight Princess.

Having been partly influenced by Bethesda's smash hit Skyrim and its 'go anywhere' approach, Breath of the Wild has since gone on to directly inspire other games with many of its mechanics. Ubisoft's Immortals: Fenyx Rising has drawn many comparisons to Nintendo's masterpiece, as has MiHoYo's free-to-play smash hit Genshin Impact. The Zelda series has once again raised expectations for open-world adventure games, just as it did in 1986.

"Every open-world game from now has to let you climb anything, go anywhere, set fire to trees and so on," says Sahdev. "It's going to be a standard. That expectation is going to be there with Assassin's Creed or the next Witcher game, and I think you're going to see that in the next few years."

He reiterates that Breath of the Wild is not some overnight success but the product of a constant cycle of reinvention that led to the divisive Skyward Sword. Having established what doesn't work, Nintendo will almost certainly focus on what does.

"Breath of the Wild is their template for the foreseeable future, so the pressure is on to make a game that sells another 15 to 20 million units," says Sahdev. "The only way to do that is to double down on what people really like about Breath of the Wild, which is all the emergent stuff: the randomisation, the weather elements, all these subsystems that interact with each other. That's the only way you top the first game."

Brown agrees, adding: "It would be a shame to throw away all the work they've done with Breath of the Wild. Because so much of it is so new, it's almost like the first game in a franchise. They've started their ideas, so we've just got to wait and see how they run with them in the sequels."

In last week's Direct, Aonuma said development on Breath of the Wild 2 is "proceeding smoothly" but there's no word on when it will arrive. Hopes will be high for a Q4 2021 release, with rumours of Twilight Princess HD and Wind Waker HD ports for Switch also doing the rounds -- all of which would be a fine way to celebrate 35 years of this storied franchise.