How to protect your intellectual property in the games industry

GG Insurance's Philip Wildman gives an overview of what intellectual property means in practice and what can go wrong

The games industry has changed a lot since its inception. Game companies are constantly seeking to iterate and innovate to stand out from an ever more crowded market.

One of the first ever IP lawsuits was Phillips vs Atari over a PacMan clone that hit the shelves in 1981, before Atari's own home console version of PacMan was ready for the Atari 2600. Atari initially failed to convince a US district court to halt the sale of Munchkin, but ultimately won its case on appeal. In 1982, the court found that Philips had copied Pac-Man and made alterations that "only tend to emphasize the extent to which it deliberately copied the Plaintiff's work." The ruling was one of the first to establish how copyright law would apply to the look and feel of computer software.

Games today are ever more complex, and development often involves multiple teams and outside help. IP infringement is not always immediately obvious or clear as to who is at fault in a dispute. This means that keeping in control and protecting intellectual property has become more important than ever, as IP disputes are continuing to rise globally.

What is IP?

So what do we mean when we say intellectual property? This can be "any type of property that includes intangible creations of the human intellect." Which covers just about everything we do in the games industry.

But more specifically there are a couple of different categories to get familiar with in games, which each work slightly differently.

Patent, copyright, trademark and trade secrets

- Patent

Patents can be thought of as protected inventions. A patent specifically is a legal protection giving the owner the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering to sell, and importing a new invention for a limited period of time.

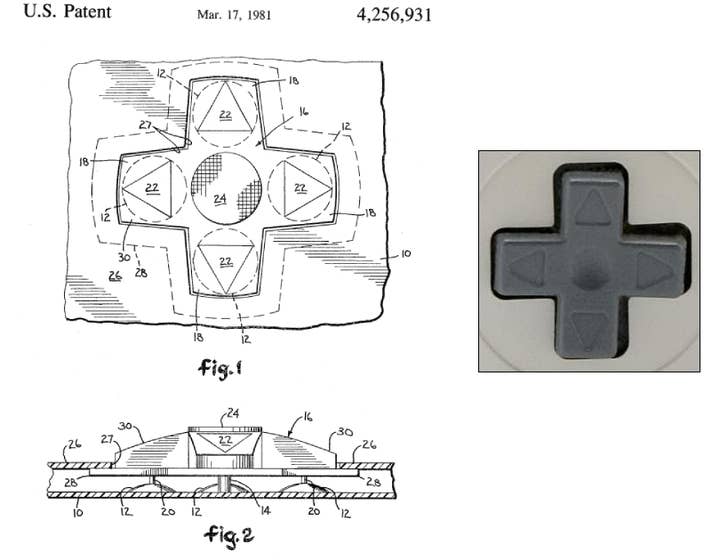

A few notable examples of protected patents include Nintendo's D-Pad, Mass Effect's Dialogue wheel, and Namco even had a patent on mini-games in loading screens which didn't expire until 2015.

If the game you are working on includes a system or mechanic that you feel is new and unique, you may want to consider protecting that with a patent.

A patent is requested by filing a written application at the relevant patent office, and if approved it will be filed at your countries patent office. There is usually an annual renewal fee to pay to keep it active and, assuming you keep up the renewals, they generally last 20 years.

It is important to remember that if you file a patent in the United Kingdom for example, this will not automatically protect you in another country. In the event of a dispute, having a patent in your home country will help, but it makes it much more difficult to claim infringement in an area where you have not protected yourself. Due to the international nature of the games industry you may want to consider an international application through the International Patent Cooperation Union, which will centralise the process and apply to 153 regional authorities. There is no such thing as an "international patent," and the grant of patent remains the prerogative of each national or regional authority.

- Copyright

Copyright is different to Patent, in that it is intended to protect the original expression of an idea in the form of a creative work, but not the idea itself.

A copyright is a collection of rights automatically vested to you once you have created an original work. Most countries recognise copyright in any formal work without a formal registration, and to qualify a work must typically meet minimal standards of originality in order to qualify for copyright (different countries impose different tests, although generally the requirements are low). Copyright generally expires after a set period of time (some jurisdictions may allow this to be extended).

If work had been contracted out, the original artist could still claim ownership to the work they produced post release

In terms of games, this could mean characters, stories, art, music, software, code, names, settings.

It is particularly important to understand whether the original creator holds the copyright, or the company that they are working for. It may be assumed that the company owns the right to the work the ultimately produce, but this is not always the case and often if work had been contracted out, the original artist could still claim ownership to the work they produced down the line and post release.

As an employer it is also common practice to include a clause in the contract that states that any work done during the course of employment, that work remains property of the company. Companies working with contractors should pay particular attention to who owns the work.

These issues can be prevented with clear contracts in place, delineating who owns the rights to what. And without a proper contract the company could leave itself open to problems later.

One example of this happening in practice, was with River City Ransom: Underground which was pulled from Steam following a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) claim filed by composer Alex Mauer who had worked on the game. Mauer said that music she produced for the game was being used without her permission.

Copyright itself can be further understood as a collection of rights, rather than one thing. These rights include the right to reproduce the work, to prepare derivative works, to distribute copies, to perform the work publicly, and to display the work publicly.

As the copyright owner, you have the authority to hold these rights yourself or to transfer one or more people. This can be done via licensing, assigning, and other forms of transfers. Hence the power of copyright gives you the power to choose the way your work is made available to the public.

Smash Bros is a good example of various copywritten characters that have been licenced out and used in a separate game by a separate company. Each character will have a specific agreement and contractual agreement between the original IP holders and Nintendo & Bandai Namco for use in the game, and one would assume money changed hands to secure these rights.

Again, make sure any transfers and limitations are made clear in any contract, so there can be no misunderstandings that lead to problems later -- whether you are the recipient of an agreement or the copyright owner.

- Trademark

You may be familiar with these symbols. Where (R) means registered trademark, and TM means unregistered trademark.

"A trademark is a type of intellectual property consisting of a recognizable sign, design, or expression which identifies products or services of a particular source from those of others." - GOV.UK

In the game industry, this generally means the logos, company names and the titles of the games themselves.

One example of a trademark dispute would be Mojang vs Bethesda in 2012. At the time Mojang was working on a game titled "Scrolls". However, when Bethesda got wind of it, they argued that word infringed on its "Elder Scrolls" trademark. Ultimately, they agreed to settle the dispute, however it is not uncommon for companies to proactively register and then fiercely protect their trademarks.

Many names are deemed too generic to trademark. In 2016 Sony tried to claim ownership of "Let's Play", trying to capitalise on the YouTube gaming community. But was rejected.

It is understandable why companies would want to protect their names from imitations. At the beginning of 2020, Nintendo applied for 39 new trademarks, and with the growing market for knock-offs and clone games, you can see why would not want a new games out there called Super Zelda Bros.

- Trade secrets

Trade secrets are like the secret sauce to your success. They are key to your company by virtue of the fact they are unknown and exclusive to you.

Three factors common to the various Trade Secret definitions are that the information:

- is not generally known to the public

- confers economic benefit on its holder because the information is not publicly known

- where the holder makes reasonable efforts to maintain its secrecy

As the games industry relies very much on innovation, protection and secrecy of those new ideas and the code behind them can be crucial to a company's success.

Just like KFC's secret recipe is held under lock and key in a safe in Louisiana, this could be the source code behind your new game engine, or a new mechanic unseen before. Or perhaps a new method of monetisation or user engagement.

Many of you that have worked in the games industry should therefore be very familiar with NDAs (Non-Disclosure agreements), which establish a legally binding promise of secrecy about a certain topic, the importance of adhering to these cannot be understated.

Should the underlying code behind the PS5, Xbox Series X & Nintendo Switch get into the wrong hands for example, their exclusive games could then be reverse engineered, emulated and modified to work on other hardware.

This also applies to embargoes, which until the embargo is listed, the information is privileged, and an early leak could cause all sorts of damage.

The first step to protection, is to ask yourself: "If 'X' got out, how bad could that be to our business?"

In 2004, Axel Gembe was charged with hacking into Valve Corporation's network, stealing the video game Half-Life 2, leaking it onto the Internet, and causing damages Valve claimed were in excess of $250 million.

The first step to protection, is to ask yourself: "If 'X' got out, how bad could that be to our business?"

Once you have identified any key secrets, then you would need to establish robust contracts, non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), and ensure any work-for-hire and non-compete clauses are properly embedded into any agreements with staff, contractors and any external parties you are working with.

Industrial espionage and disgruntled employees and hacking does happen, so beyond written contracts, think about who has access to what files and how much damage each person could do, and how to limit a breach before it happens (which hopefully it never will, but it does not hurt to be safe!).

Am I infringing IP?

So now we know about the various types of intellectual property. But what does that mean for you, what are you allowed to do and how similar can your work be to another?

When working on something new, every case will be different but ask yourself: "If it looks like a goose, swims like a goose, and sounds like a goose, could I be accused of misappropriation of the original goose?"

"If it looks like a goose, swims like a goose, and sounds like a goose, could I be accused of misappropriation of the original goose?"

The real answers could be more grey than black and white, and you may want to ask yourself, could you afford the legal costs if someone took you up on it?

My advice would be to check early and check often. Some things may be easily recognised and picked up easily, but it might not be immediately obvious that you could be unintentionally infringing IP.

This is an area that insurance may very much be able to help with. There are certain types of insurance that are designed to cover intellectual property disputes and will pay out for the legal defence costs and settlements. You should still adhere to best practices as insurance assumed any breach was unintentional, but it could provide a very welcome safety net.

What about Fair Use, Easter eggs and homages?

Fair use is an allowance in US Law that allows for use of copywritten material in certain circumstances. Broadly it is allowed for non-commercial research or study, criticism or review. However many countries do not make allowances for fair use so do not assume you are safe. However a general rule of thumb is that if you are making money off the back of somebody else's work, tread very carefully.

Easter eggs, references and homages to other properties are common in many games, but there is a fine line when it comes to copyright infringement.

There are a couple of different types of Easter eggs that can be found in games, (and not all Easter eggs are references to other properties).

References to other works you own is usually fine (assuming there are no unusual licence deals). As Disney now owns LucasArts, they were able to include Guybrush Threepwood in the Force Unleashed 2.

Then there are parodies and references to properties you do not own. This then depends on whether this is a direct or indirect reference. The difference being coins popping out of blocks is an indirect reference to Mario, whereas an Italian plumber dressed in red and blue would be a direct reference. Again, tread carefully and if you are unsure, seek permission.

Parody is a form of critique and fair use law may cover this type of reference, so you may be able to parody other games. But bear in mind, even if you are protected under fair use law, this does not stop the original IP holder sending you a legal threat anyway. So ask yourself if this is worth the risk?

We so far have assumed you are aware and in control of everything that goes into your game, but this is sometimes not always the case. In 1980 Warren Robinett famously snuck his name into the Atari 2600 Game Adventure, which is assumed to be the first ever video game Easter egg. But this was done unbeknownst to Atari. Although many Easter eggs are intentional, individual developers do occasionally sneak things into games -- rarely with malicious intent, but this can cause major headaches.

There is another less well-known story of the Punch-Out game, in which a character is reading a comic. The contents of which (a screengrab from a real Sailor Moon comic) was hidden to players but with a boundary-break, it was then there for the world to see (including the Sailor Moon publishers) who were not happy, and it cost Nintendo millions.

The safest course of action is to always seek permission from the original IP holder before using any material that is not your own original work. Keep a record of that permission filed away for future reference -- you may need to call on it in 10-20 years.

What is my IP worth?

Valuing IP is not an easy task. How much is your brand name worth after years of marketing? What would you take if someone offered to buy all rights to your property? There are a couple of different ways to value your IP.

The Cost Method is simply the costs you incurred in creating a property, this would be in terms of labour, equipment, trials and tests, and so on.

Ask yourself: if we lost the property, how would that affect our future earnings?

The Market Value method tries to put a figure on what the property would be worth if sold or licenced out. This is difficult to put a value on, as when IP is licenced out as no two deals are the same. But you could ask yourself, how much would I take to sign over all rights to the property?

The income or economic benefit method focuses more on how much value the property adds to the business over time. Ask yourself: if we lost the property, how would that affect our future earnings?

None of these methods are particularly accurate, but it helps to start considering how valuable your IP really is to you and your business, and what steps you should be taking to protect that.

What steps should I take to protect my Intellectual Property

This is a quickfire guideline on what to do:

- Take stock of what Intellectual Property you have, and identify what needs protecting

- Register your trademarks

- Register your patents (if you have anything patentable)

- Protect your copyrighted content with robust contracts between all parties

- Make it clear who has ownership of any IP -- especially when using contractors and external companies and content providers

- Make sure any trade secrets are protected with NDAs between all parties

- Limit who has access to what

- Look into your system security to prevent hacking breaches and leaks.

- Engage with lawyers early and often (they are much cheaper before you have a problem)

- Look into getting insurance

Help, I've been sued!

Firstly, do not panic and do not admit fault until you have spoken to a lawyer.

It is rare you would be immediately summoned to a court case, normally you would receive a legal threat or cease and desist letter before it reached any court, and there should be a reasonable timescale to respond.

Unless you are absolutely confident you can remedy or take down whatever you are being accused of yourself and that would be the end of it (assuming you are happy to do that), then you should be speaking to lawyers as soon as possible. Especially if the other side is claiming damages of any sort.

If you have insurance, notify your broker, and get their advice as to what is and is not covered under your policy. Before engaging in a legal battle, find out if the insurance would cover the costs.

Help, someone is breaching my IP!

Firstly, do not panic! And try and avoid wading in yourself. It could be a simple misunderstanding, or a coincidence and perhaps possible to solve amicably. But before taking any action gather as much information as you can, including dates and times, then seek legal advice as soon as possible. Something that may appear benign, could turn nasty very quickly.

Assuming you have already established ownership and rights to your own IP, you should be in a reasonably good position. However, if your own game is still in development and you suspect someone is working on a rival game or trying to beat you to the punch things could be trickier.

If you do not have established ownership already, there may unfortunately not be much you can do. There is a fine line between a game being similar, and outright copyright infringement. Some companies can take advantage of making a new game just different enough to an already successful formula.

You will need to make the decision on whether you want to get lawyers on the case (and the associated costs, which can quickly escalate) or not.

Mitchell Corporation complained to PopCap that Zuma was a copy of their game, but unfortunately for them were not able to win the case.

To have infringing content taken down, the normal course of action would be to engage with a lawyer and complete a Digital Millenium Copyright Act (DMCA) takedown notice, and potentially start taking legal steps.

Philip Wildman is managing director of GG Insurance, which prides itself on passion for and understanding of this industry. GG takes a proactive approach to learning and understanding as the industry constantly changes, on the belief that it is crucial to not only understand insurance inside out, but the games industry itself. For more information: info@gginsurance.net