What are the biggest changes impacting the games industry?

At the NG20+ conference, Rami Ismail looked back at a decade of games industry and how it can inform indies' decisions going forward

If 2020 has proved anything, it's that the games industry can catch any curveball life has to throw.

Entering the year, it's fair to say that many AAA studios didn't strongly believe in remote working. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said that it wasn't viable as a permanent setup. And yet, just yesterday, Square Enix announced its intention to make remote working permanent for its Japanese staff. Online events are becoming the norm, and that digital component in industry gatherings is here to stay, while remote working slowly becomes the new normal.

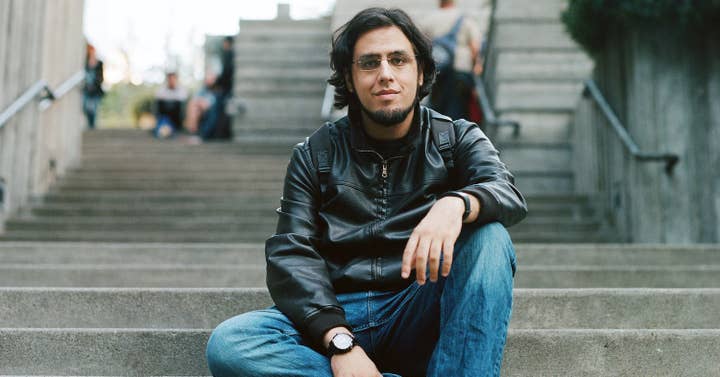

"Game development is nothing if not flexible," said Rami Ismail in a NG20+ talk released earlier this week. "I've only been around for one decade, but a lot has happened in that decade. Steam happened, mobile happened, Twitch happened, Minecraft, Fortnite, Game Pass. So much has happened and so much of that severely impacted how we do business."

Ismail was one half of Vlambeer until the indie studio disbanded earlier this year,. He's now a consultant for indie developers, particularly focusing on emerging markets, and executive director of gamedev.world, a free online conference in eight different languages.

In his talk, titled "Reinventing game development," Ismail looked back at what's changed in the industry over the past decade, speaking to more than 30 independent, AA and AAA developers from all around the world in the process.

"At first I thought I'd make this a talk about what has changed in the last year, what has changed now that COVID-19 is such a large part of our reality," he explained. "But talking to people, it really quickly became clear that there is so much more happening all the time."

Live streaming

The most commonly mentioned topic during Ismail's discussions with developers was live streaming and how it radically transformed game development.

"There has been nothing that is more disruptive to gaming than live streaming," Ismail said. "I remember six years ago a man from Justin.tv came to my booth at PAX and asked me if I could stream my games on Justin.tv because it was gonna be a big thing. That's less than a decade ago. What Twitch did is it fundamentally changed our approach to designing games and to marketing games. Games are now built to be replayable. Because if a streamer keeps playing your game, then it is very likely that you'll just have free marketing."

"There has been nothing that is more disruptive to gaming than live streaming"

That also created a shift in genres, with the emergence of battle royale games and a resurgence of multiplayer shooters.

"Those genres have retained or gained a lot of popularity just by grace of being easily streamable," Ismail continued. "The very prominent note right now is people designing for Twitch. And not designing necessarily to integrate with Twitch, but just designing their game with Twitch in mind. How do you make your UI and design easily readable for a viewer? How do you make sure that people have time to chat or talk while they're playing your game? Things like that have genuinely shifted how we design our games."

Live services

The emergence of live streaming is closely linked to the ascent of games-as-a-service, popularised by titles such as League of Legends, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, or Destiny. Live games do mostly remain the realm of AAA studios though.

"We've seen quite a few attempts at that -- some successful, most of them deeply deeply unsuccessful, because it turns out that making games as a live service is not something that you can easily do as an independent creator," Ismail said. "A lot of us have learned lessons from mobile though, who have been working with this sort of [approach to] game development for almost a decade now. The knowledge of retention, engagement, funneling, the way of creating games that are meant to keep engaging, meant that new business models were needed."

Subscriptions and microtransactions are the most popular solutions created to support this new era of live games, but these have not been free of controversies. However, the industry does need to keep coming up with ways to reinvent itself as players now expect support in the long term.

"The industry keeps pushing to find a way to move away from that premium model that I personally love," Ismail said. "But it is abundantly clear that if we're going to be making the games that are selling right now, that those models might not be as sustainable as we thought."

Subscription models

Among these new standards emerging, Ismail believed that subscription models are the biggest thing that developers should pay attention to. Services such as Apple Arcade or Xbox Game Pass will continue to impact how the industry works, moving away from a direct relationship with consumers.

"[These] platforms have taken a new role as curator and as a funding platform," Ismail said. "It creates this new paradigm for how we make games. Instead of trading games business-to-consumer, suddenly we're thinking about how we make games business-to-business. It could be highly disruptive to the workflow of developers."

"Instead of trading games business-to-consumer, suddenly we're thinking about how we make games business-to-business"

Whether this is a positive or a negative for indies is hard to say at this point, Ismail added. Developers with established titles can benefit greatly from subscription services, but it might not be as easy for newcomers.

"For upcoming developers, it means that they have another middle man they have to convince of the quality or viability of their game. As an industry we obviously have to worry about what [these platforms] will be like in the future.

"If these models become prominent, will the amount of money that is being spent on games for those platforms sustain, or will that go away? How will this affect our industry? The views that people had on this were incredibly varied -- some people saw this as an incredibly positive thing for our industry, a lot of people saw it as a thing that we have to approach with a bit of skepticism, and some people basically said that the games industry is dying."

New platforms

The last decade brought new ways to consume games and new business models, but also a few new platforms that are transforming the ecosystem -- such as the Epic Games Store, VR and Google Stadia.

In the meantime, historic platforms such as Steam have evolved in such a way that it's more difficult to be successful. New games on Steam in 2016 rose 40% over the previous year. In 2017, it increased another 53%, before finally slowing down in 2019.

"The platforms have shifted back to being in a curator role, which is interesting because for a while there was this very hard push for platforms to be open, to be as accessible to every developer," Ismail said. "And over the past years we've seen that result in what Steam looks like right now, which is an open platform. Anyone can put a game out there if they pay the small entry fee.

"But it has also led to a lot of problems. It is harder than ever to get your game noticed on Steam, unless you have an established fan base or you have good marketing. As Steam tried to deal with the influx of games on their platform, it became harder and harder for games to stand out."

Ismail pointed out that most of the developers he talked to have either seen small dips in revenue over the past decade, or small increases, but nothing drastic. Steam also continues to report increased profits.

"It's obviously not that Steam is not generating revenue anymore, there's just more losers now than there were before. There's more people that are launching a game that is unsuccessful. Obviously that is a function of a platform like it. But it also makes it very interesting that we have a few platforms out there that are very strictly focused on curation."

"It's not that Steam is not generating revenue anymore, there's just more losers now than there were before"

He mentions Apple Arcade and the Epic Games Store, which for now has a more curated approach than Steam, though it is meant to open up in the future.

"It is interesting to see that counterweight. Some of the people I spoke to, who have been in the industry longer than I have, have said that it's basically a wave function that keeps repeating over and over, and that the shift between openness and curation will continue into the future.

"And for now it seems that they're right, that this is going to be where we're going to be: small curated storefronts rather than algorithmic storefronts that are pushing different niches. So that's an interesting thing to think about when making decisions for what you're going to be doing."

Related to platforms, Ismail also touched upon something Mike Bithell recently mentioned in a GamesIndustry.biz Live: Academy talk: developers should find a space where no one else is and take these opportunities quickly.

"The indies are still moving mostly to open platforms, because those platforms are more accessible. But a lot of people also brought up a lack of competition. If you can be on a platform first, that will net you quite a beneficial place in a more curated space. A lot of developers that I've talked to were pretty happy with launching on things like Stadia, or VR, or early on Switch."

Boutique publishing

The increasing number of platforms had a direct impact on the rise of a certain type of publisher. While self-publishing was in vogue until the mid-2010s as developers flocked to Steam, the second half of the decade saw boutique publishers going from strength to strength.

"A lot of indies are struggling to keep up with launching on all platforms," Ismail said. "It is common wisdom at this point [that you should] launch a game on as many platforms as possible to spread your risks. Most of the tool sets -- including GameMaker which we [used] at Vlambeer, but also Unity and Unreal -- out there allow you to publish to most of these major platforms without too much hassle.

"The thing that takes a lot of indies a lot of effort and that is stopping them from launching on a lot of platforms is just the overhead. As the amount of platforms is increasing, it seems that there will be an additional role for boutique publishers to take care of that. Ironically the biggest need for boutique publishers comes from the existence of boutique publishers."

"Ironically the biggest need for boutique publishers comes from the existence of boutique publishers"

Ismail clarified that by 'boutique publishers' he means smaller companies with a distinct approach or identity, such as Raw Fury (created in 2015), Annapurna Interactive (2016), or the founding father of them all, Devolver Digital (2009). While these present an undeniable opportunity for developers, they can also be a threat.

"They're usually highly curated publishers. Before those existed, indies were competing with indies in terms of marketing, and nowadays it is almost impossible for almost everyone I spoke to to keep up with the consistent output and the brand awareness that a Devolver Digital might have."

This change in the publishing landscape could mean a change in the funding process too, with the developers Ismail talked to indicating that most of the funding in the near future will be primarily front-loaded.

"Before, you would make a game, get some funding, release your game and then make some money after your revenue split. A lot of people are expecting that the model will shift more towards getting a larger bag of money upfront or throughout development, and then seeing less of the revenue on the other end per se.

"That also creates a necessity for funding, and self-funding for new projects is increasingly rare. I generally thought self-funding would be on the rise over these next few years, but almost everybody I spoke to was pretty down on the ability of companies to self-fund."

Direct marketing

Marketing has also evolved, with more and more channels available to developers, allowing them to communicate more directly with their audiences. Communication in the industry is now more focused on companies rather than specific games.

"A number of developers said that marketing is becoming less important to them. What they mean is that the way people market their games is less actively pushing for things, and more making sure that, when there is passive movement, that they jump on top of [it] and are aware of [it]. A lot of them expressed that the focus for awareness around their games is now focused more on a brand than on the direct marketing of each individual title.

"People are getting better and better at creating temporary alliances for marketing purposes"

"What is interesting is that direct marketing is extremely fragmented. There are many ways to market your game to consumers, and as an indie doing it through your own YouTube channels or Twitch stream, it's still relatively hard. That has created a sort of new middleman position for a focus on critical mass."

Ismail mentioned that Jeff Keighley pretty much successfully privatised game announcements during the summer of 2020, with the Summer Game Fest. But there were a few smaller, very successful efforts such as the Wholesome Direct or LudoNarraCon.

"People are getting better and better at sort of creating temporary alliances for marketing purposes, in which they target very specific niches directly," he highlighted.

Cloud gaming

Whether it's Google with Stadia, Nvidia with GeForce Now, Microsoft with xCloud, Amazon with Luna, or Steam with its Cloud Play beta, everyone wants a slice of the cloud gaming pie.

"A lot of this is an obvious, almost inevitable evolution of all of the above -- the live stream, the live services, the subscription models," Ismail said. "Everything that is there pushes these companies to want more control over how people play and access games, and give them less obstacles on the way there, while also getting as much money out of that.

"The technology is functional-ish and it works well under the right circumstances. So far my personal opinion is that every platform out there has dropped the ball incredibly hard. Stadia feels stagnant, despite being a revolutionary technology. Nvidia ended up in a lot of controversy about putting games on the service that weren't signed to [it]."

"Every platform [in cloud gaming] has dropped the ball incredibly hard"

So despite noting a few "inspired choices," Ismail said it's going to be years before cloud gaming properly catches on.

"The good news though is that the people that are using these cloud gaming services seem happy. The bad news is that the people that seem to be using these cloud services are happy. Again, this will push the games industry very hard towards a more business-to-business sort of focus, and how that is going to play out for different types of games remains a question. It's something a lot of people are thinking about and are nervous about."

Community management

Everybody Ismail talked to stressed community management as one of their increased focuses this past decade -- a trend they see continuing going forward.

"Earlier I said marketing is less important and branding is more important, and what most people mean by branding is community management. Several studios said that it is probably the main driver of their sales and brand awareness, and that it is potentially the most critical part to their success.

"The games that are successful are overwhelmingly games that have a personality attached to them"

"With that comes increased competition, and half well done community management is becoming a real risk to studios. You can either choose to focus on it entirely or not at all but doing sort of the 'I will check the Steam forums once a week' is going to be actually negative towards your community in the future."

He stressed examples such as elaborate Discord servers, very active personal Twitter use, or a TikTok presence as strategies developers have been using to appear more personable.

"You see it all the way from AAA to the smallest indies out there. The games that are successful are overwhelmingly games that have a personality attached to them. And for a lot of the upcoming publishers, you can tell that the tone is they're selling point. It is not necessarily the game, even though the games have to fit the tone of the publisher, but it is the tone that people can see and get from them. The sort of feeling of community, the sense of belonging that people get."

Social responsibility and regulations

Over the past few years, there's been an increased awareness of the social responsibility and influence of games as a political medium. Publishers now regularly take responsibility for offensive content in their games for instance, closely following the evolution of our society. But there's two sides to that coin, Ismail said.

"Even in large AAA games, you're seeing a lot of increased effort to do the right thing, even if they have to do it quietly. Two of the three most recent Call of Duty games feature an Arab protagonist and [Modern Warfare] even allowed to play her. So there is definitely a push towards being more socially aware.

"The flip side of that is that obviously where games do not do the right thing, there is increased scrutiny from governments and regulatory bodies. A great example is the microtransaction discussion. It is increasingly clear that if our industry does not moderate itself and does not regulate itself, that governments will start doing it. We are too large, we are too influential to stop that from happening. So if we don't do it, they will."

CEO of UK trade body UKIE, Jo Twist, recently addressed this evolution, exploring the right response to "a new phase of regulatory scrutiny" for the industry.

Unionisation

One example of regulation that could come from within the industry, whenever it fails to do the right thing, is unionisation.

"There's different levels of necessity for unionisation around the world, but it is incredibly needed in a lot of the primary industry locations that we have," Ismail said. "The efforts so far have been scattershot and various in efficiency, but they're very real, they're very genuine, they're not going anywhere and they have a very real effect on upcoming talent, which I think is great.

"Either way, there is great movement in the industry in the forms of co-ops, increased discussion of crunch, and increased discussion of worker power, like the ability for workers to organise, and to really fight and work together for better conditions. So I think in a way this is a good way of the industry taking responsibility for its own. And if that takes a little painful stuff on management, and so be it."

Emerging markets

Europe, America and Japan have historically been the cradle of the games industry. But emerging markets are becoming more and more prominent, and indie developers should be paying attention to that discussion.

"The growth of emerging markets has been ridiculous. Locations like MENA, India and Southeast Asia have been the focal points of a lot of studios. And that is not just localisation -- it includes entire community management positions, offices, representation, in those territories.

"There is definitely a push around the industry to localise for these territories and to at least be aware of the cultural sensitivities and the cultural opportunities of each of these markets. A lot of the great games of the nearby future will probably come from territories that many of us now don't even think of as places where game development happens."

Continued democratisation

The final talking point in Ismail's discussions was the continued democratisation of game development, led by the increased accessibility of the tech behind games. The number of game engines is on the rise, providing more opportunities than ever to aspiring devs.

"There is a huge movement of game developers that are not doing this for any commercial purpose"

"Somebody called it the 'designerisation' of game development," Ismail said. "There is an increased focus of tool sets on the ability to create with a limited technological knowledge. That has led in many ways to an increased quality of output, and an increased number of output from people that are otherwise industry averse, or just not very technologically capable or specialised.

"The good news is that that has created increased variety in diversity of games, but also an increased diversity in why games get made. There is a huge movement of game developers that are not doing this for any commercial purpose. With this diversification, we can watch for trends or niches, things that could be interesting to play around with or be inspired by."

Looking ahead

There are currently a lot of companies spending money on the opportunities Ismail highlighted. As an indie developer, being able to take one of these opportunities is an "incredible privilege," he said.

"Huge shifts -- that are likely in these next few years -- will probably come and go incredibly fast as the industry changes. One developer basically said that if they could get a deal with Stadia, they would take it now, because that might just be gone in a year and then the money is gone as well. If there is an opportunity now, take it now.

"The other [thing] is that a lot of studios are making really hard choices about whether they're committing to staying small or growing fast. The teams that I talked to that were ten to 12 people were generally pretty confident about their ability to survive, and so were the people and teams that were larger than a hundred people.

"But the space in between seems pretty volatile right now, and a lot of companies are having a hard time figuring out how to fund, continue, or grow, or even just stay stable in the current environment. Especially with the upcoming potential recession affecting our industry after COVID-19, a lot of studios in that mid-group are a little nervous about what to do right now."

The overall sentiment was one of constant change, with uncertain times ahead.

"A lot of developers I spoke to expressed concern about the upcoming shift from business-to-consumer to business-to-business, and what it means for the industry," Ismail concluded. "And lots of developers don't really see a choice but to participate in that shift, because revenue sources are unpredictable and free money is nice.

"But they also said that uncertainty is nothing new and there's this discussion about how our industry has been crashing since 2010ish, with different segments of our industry hitting the ground and bouncing back up. But across everybody I talked to, it was abundantly clear that our greatest strengths as an industry, remains being flexible, paying attention to new realities and opportunities, and adaptiveness."