Do we even need a Netflix for games?

All forms of entertainment have perfected the on-demand model - except video games. We speak to the firms striving to rectify this

"Netflix for games."

It's a phrase many a journalist has seen in his inbox over the years, often attached to press releases regarding yet another ambitious but risky games-on-demand service.

While the number of these services has risen over the past year (encompassing the likes of Hatch, Jump, Utomik, PlayKey - the list goes on), it's impossible not to read these promises of cloud-powered convenience and recall the first time someone tried this.

Announced back in 2009, OnLive positioned itself as the future of video games: no more discs, installs or even individual sales - just one monthly subscription and access to countless games through any PC (or its ill-fated microconsole).

It launched, but it never caught on.

The company made a second attempt by tying into Steam, allowing players to access their own library from other devices without the need to download.

This, also, never caught on.

Eight years of hard lessons and failed plans led then-general manager Bruce Grove to one conclusion: "Streaming games using GPUs via the cloud is a bad idea."

"You can't make it scale," he elaborates for GamesIndustry.biz. "Everyone who has ever tried this - myself included - has discovered it's not really the technical problems of latency, bandwidth or all the other things people talk about - it's the operating cost.

"You're essentially taking all the power of a computer and putting it in the cloud. If you want to run a PS3 game in the cloud, it's done by building a whole load of servers that look like PS3s. If you wanted 50,000 people playing at the same time, you need 50,000 machines all running those games. It just becomes unrealistic. If you have 10,000 players at peak time, you need 10,000 GPUs in the cloud. What are they doing the rest of the time? They're sitting idle, not doing anything which ups your costs.

"The cloud is supposed to be elastic, it's about growing and shrinking your resources as and when you need them. The cost of power for operating all those GPUs is enormous."

"People are used to consuming media [instantly]. You can just watch a movie, or listen to music. The path between you and actually playing a game [is much longer]"

Doki Tops, Utomik

And yet you have the likes of Hatch, Jump, Utomik, PlayKey - the list goes on. Oh, they've done away with the video streaming in favour of partial downloads or cloud-carried render commands, but the final product is much the same. Is the demand for an online library of video games strong enough to draw out these start-ups, or are they merely honing the technology just to see if it can be done?

"For a lot of people, gaming feels like a closed off space," says Utomik CEO Doki Tops. "The crazy thing is games are bigger than movies and music combined - and yet still that mindset is different. It's almost behind this veil of hardcore users that give it a certain name or perception.

"People are used to consuming media [instantly]. You can just watch a movie, or listen to music. If you look at the path between you and actually playing a game, it's a long path. In the history of everything, reducing that path to the most efficient one always leads to a new innovation and a new era."

This certainly rings true in an age where even console players face lengthy waits for installs or day one patches before playing a new physical purchase. In fact, the games industry is still playing catch-up with all other forms of entertainment.

"At the end of the day, it comes down to convenience," says Vesa Jutila, co-founder of mobile service Hatch. "Nobody wants to go and download a movie, because you can just press play on Netflix or whatever. Almost nobody buys CDs or downloads MP3s because you can just go to Spotify and play whatever song you want. It's a fundamental paradigm change that has hit all other forms of entertainment - except gaming."

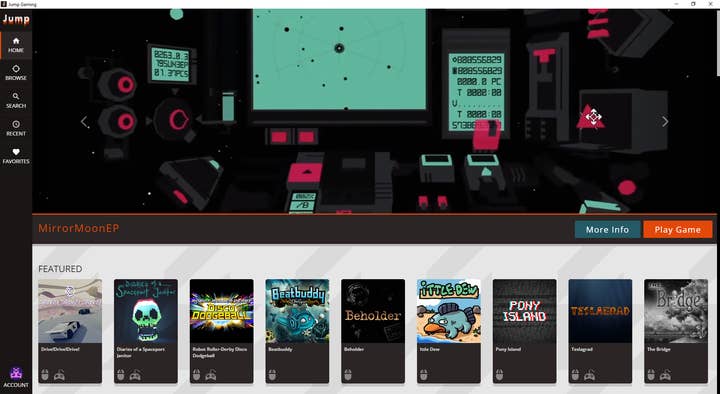

Jump CEO Anthony Palma adds this demand stems from within the industry, not just the audience it serves - and he claims that indies are the ones who will benefit most.

While there are AAA on-demand services like PlayStation Now and Xbox Game Pass, many of the titles in these libraries are established hits. Meanwhile, a casual look through the likes of Hatch or Jump show countless indie titles yet to achieve the success they perhaps deserve.

"[On-demand is] absolutely necessary... to help game developers add long-tail revenue to their premium games," says Palma. "If you talk to any indie developer today, they'll tell you their games are getting buried on traditional stores and they're actively seeking new revenue opportunities to break through the noise. The Netflix-style idea has to be done right - proper technology for the medium, heavy curation for game quality, multiplatform accessibility, and so on - but it's the logical next step in the lifecycle of premium content that games don't have right now.

He continues: "How, where, when, and even why we play games is shifting constantly in the industry, and the convenience of an on-demand, all-you-can-eat subscription service versus physical ownership is an inevitable trend - just like it [has been] in every other medium. Our research showed a significant level of interest in a service that solved the problems seen in previous attempts, whether those were technical or business model issues. We've built and positioned Jump around these findings to ensure we're a great service for both gamers and game developers. And the appetite on the game developer side is growing as the frustration with premium stores and bundles grows."

Hatch communications manager Joseph Knowles adds: "People talk about the golden age of television that Netflix and other streaming services has brought, and I think a lot of games executives look at that and say, where the hell is our golden age?"

Of course, the demand for convenience and a packed library of instantly accessible games is arguably much like the call for backwards compatibility on consoles - a nice feature to have, but one only a fraction of the userbase embraces. As such, Grove remains unconvinced that a Netflix-style games platform could ever take off.

"[On-demand is] a fundamental paradigm change that has hit all other forms of entertainment - except gaming."

Vesa Jutila, Hatch

"When did you last binge five different games in an evening?" he argues. "Games are immersive experiences. We go into a game, and that's what we want to play. Whether it's a 10-hour or 200-hour experience, we're engaged by it. If you create Netflix for games, who's your audience? Who's your market?

"Look at EA and Origin: you have FIFA next to Battlefield next to The Sims. There's a reason they have three different marketing teams, different business models. If I create a Netflix for games and I put Borderlands next to Cake Mania just because I want a large content line-up, how am I acquiring customers? Who's my market, who's my audience?"

Instead, Grove believes the future lies in publishers creating on-demand channels of similar content - e.g. a simulator specialist building a Netflix for train, plane and farming sims - which is something his new venture Polystream is working towards. And he still believes a service that would enable users to access their own game collection on any device could be a hit.

"My Steam library is 100+ games, and I know lots of people who have much more than that," he says. "Very few people can install their entire Steam library. Maybe I fancy playing a game I remember from ten years ago - but do I want the hassle of installing it, or do I just want to play it? That's kind of the Netflix for games model, except it's my library, my content curation. I want access to that, to be able to hit save and know that it's still there wherever I log in next."

Furthermore, he observes that expansive libraries of content aren't necessarily as valued in other entertainment industries as you might think.

"When people talk about Netflix for games - guess what? Netflix doesn't want to be Netflix for Netflix," he says. "They want to be HBO for streaming, which is why they're now a first-party producer and they've culled so much of their own content. They couldn't monetise it because people weren't interested in it. What they want to do is be the tier-1 provider of the best content. If you want to be Netflix for games, become a developer with top-tier content. Become Valve for streaming."

Utomik boss Tops agrees with this, at least: that exclusive content will eventually be the main attraction for each service. He also doesn't believe that a Netflix for games would ever replace the traditional business of major releases - it will merely complement it.

"I'm very curious about the future of premiuim game sales," he says. "I don't think it will be what happened to movies, where people don't really buy DVDs any more. For games, the business model will remain [centred on] selling a premium game for $60. Everybody's been saying that model is dead, but there will always been [certain franchises] that can get away with it - I can't go to Activison and say I'd like to put Call of Duty on Utomik. I don't even bother, because I can't make a business case for them.

"The movie industry has a lifecycle management: first it'll be in cinemas, then home release, then on-demand and so on. The games industry right now is very opportunistic, companies will try things and see what sticks. If it doesn't do well on Steam, they do discounts and then more discounts - I think that model will change, because of subscription. Instead of going into discount mode... In my mind, the concept of discounts and Steam sales will die off because companies will just say, what is the right time to put a game into subscription?"

"[On-demand is] absolutely necessary... to help game developers add long-tail revenue to their premium games"

Anthony Parma, Jump

Meanwhile, Hatch's Jutila argues that such services will help indies and smaller developers, as the barrier to sampling new games will be much lower for players: "When games are delivered in an on-demand fashion, trying out new titles becomes really easy. You start playing and if you don't like it, you move on - there's no hassle of going to an app store, downloading something, installing something. It's just instantly available behind a play button."

Tops agrees, but stresses that established and popular titles are needed to draw people to the platform in the first place. Utomik attempts to drive curious players to games they may not have encountered by placing them next to known brands on the storefront - but this highlights another issue for Grove.

"If Battlefield's at the top and everyone wants to play it, the games at the bottom - how do we compensate people for them?" he says. "How do we make sure that revenue model... if I'm going to say $10 per month, all-you-can-eat subscription, what's left for the person at the bottom whose game is never touched?"

And herein lies another issue: convincing players to pay for a subscription. No matter how reasonable your price, you're competing with the monthly fees for Xbox Live, PSN and even non-gaming services like Spotify and, of course, Netflix. (It's worth noting both Xbox and PlayStation offer free games with their subscriptions, although the titles change every month).

Jutila remains confident that, with the right offering, one more subscription is easy to justify: "Subscription services seem to be working with consumers, they love consuming entertainment as part of a subscription," he says. "That's actually the oldest model of consumption - newspapers were doing it a hundred years ago. It's a very natrual way of paying for services.

"It's also the best way to monetise a mass market audience. If you think about free-to-play, that's only monetising a fraction of players. But there's so much more money on the table that the industry can go out to get."

But, as Grove has observed, how do developers monetise this audience? Both Utomik and Jump pay studios based on how long subscribers actually play their game - with Jump estimating it pays out 25¢ per hour per player to developers. Not terrible if your game becomes popular, but if it languishes on the store untouched, it's not the most tenable situation for small and indie developers.

Tops stresses that Utomik's audience is more open to new experiences: "If I'm an indie and I ask 1,000 Steam users to play my game, I'm lucky if 0.1% of those users will buy it... It's not unheard of on our platform that if we launch a new game, even if it's an indie, 2% or 3% of all subs will try it out. The only ones that can do that on Steam are Call of Duty and the top of the line franchises."

Meanwhile, Palma says his firm times the addition of games to Jump's library to capitalise on a decline in premium sales, opening up a new revenue channel when the launch hype has died down.

"Netflix doesn't want to be Netflix for Netflix. They want to be HBO for streaming. If you want to be Netflix for games, become a developer with top-tier content. Become Valve for streaming."

Bruce Grove, Polystream

"We work with developers to bring their games to Jump at the right time in their premium sales cycle, typically after sales have been either completely exhausted or have flattened significantly, to make sure we're not cannibalizing any potential premium sales," he says. "We've actually delayed a couple developers who wanted to bring us brand new games or ship exclusively with us, because we wouldn't be better for them than premium stores until we're much bigger.

"Given these games are at the end of their premium lifecycle, this is likely revenue from users who never bought the game in the first place, meaning it's a completely complementary, new source of revenue that adds to their premium sales rather than subtracting from them."

Even so, with the rise of Hatch, Jump, Utomik - and no doubt more to come - one question remains: how many on-demand services could the industry sustain? Netflix dominates the movies space, with a few rivals in Hulu and Amazon Prime. Surely only one of these firms can be established as the Netflix for games?

"In my honest opinion, I think five to ten could survive," says Tops. "The top three, as usual, will take the majority of the market, but there will be more niches. As with any services, though, you can't have too many but people will gravitate towards two or three."

Jutila concludes: "At the end of the day it's all about content. We're not asking for exclusivity, we just want the best games.

"From the developer's perspective, there's always some kind of cost in terms of management and how many platforms you want your game to be available from, and that of course will ultimately limit the number of viable services out there.

"That's why it's important to be first to market, because it gives you the chance to start building a network of relationships with the right content partners and start building a userbase, because the more users you have the more developers will want to put games on your platform. Once you're ahead in that, it's very difficult for your competitors to catch up."