"We have to remember it's a game": Mixing anti-cultism and action in Far Cry 5

Creative director Dan Hay discusses reactions to Ubisoft's upcoming shooter and how the Far Cry team touches on topical themes

The announcement of Far Cry 5 received a different sort of attention that it might have done in any other year. Arguably, this is not attributable to anything Ubisoft or its Montreal studio did but rather the world outside the games industry.

The pitch is simple enough: explore the open-world of the fictional Hope County, Montana as you take down a religious, extremist cult. It's a less exotic setting that past Far Cry outings, but the formula seems to be firmly in place.

However, it's announcement in May amid rising political and idealogical tension in the US prompted a wave of opinion pieces and columns pondering whether Far Cry 5 would be a statement against the extreme right wing views that continue to dominate American politics, and a criticism of President Trump's more vocal supporters.

Naturally, long development cycles mean work on Far Cry 5 began long before the recent discourse in American culture, but its another example of how outlandish video game narratives are becoming all too real. Bethesda faced similar circumstances with the launch of this year's Wolfenstein II, with exec Pete Hines telling us: "It's disturbing that Wolfenstein can be considered a controversial political statement."

We caught up with creative director Dan Hay, and asked him how his team had gauged the initial response to the game.

"When we were building Far Cry 5 and its themes... sometimes I get asked the question 'well, how did you know?' and obviously we had no clue," he tells GamesIndustry.biz.

"It's been a very strange experience. Typically when you work on games, you go outside for a smoke break or to have a beverage and you chill out, and you end up hearing conversations in the world that are nothing like the spaceships you're making or the dragons you have in your game. It's really strange working on Far Cry and to hear people talking about stuff that could be in your game. It's bizarre. It's not something that we planned, but it's certainly something that makes for a unique experience to be working on Far Cry 5."

Perhaps it's the decision to set the game in the US that makes the game appear to be so bold in the story it's trying to tell. Had Far Cry explored another, more exotic locale, it arguably wouldn't have prompted such a reaction - but bringing the series to America is something Hay has been pursuing for years.

"When we finished working on Far Cry 3, we were thinking about where we wanted to set the next one," he says. "We were kicking around the idea of setting it in the United States, but we didn't know what to do in terms of themes and locations."

Is that not an odd fit for a series that has taken players to tropical islands, war-torn African nations, the mountains of Nepal and even the Stone Age? Far Cry has always positioned itself as a franchise built on frontiers.

"It's really strange working on Far Cry 5 and to hear people talking about stuff that could be in your game. It's bizarre. It's not something that we planned"

"Sometimes it's your own backyard that's beyond your imagination, more than being able to get on a plane and go somewhere else," Hay argues. "A lot of the team had travelled and experienced different things, but there was just this idea of putting it in your own backyard. But at the time we couldn't find the stickiness of the idea, so we put it on the shelf and it just sat there for a while - but it's one of those things that just kinda festered. It was bugging me. I really wanted to figure out a way to take Far Cry to the States.

"We made Far Cry 4, then Primal, and then there was a moment about three and a half years ago where we had the opportunity to talk about where we'd take Far Cry 5 and we brought back the idea of bringing it to the States. We thought it might be the right time."

To choose a location on which to base their new world, Hay and the team thought about the closest to a frontier that you could find in the USA. The idea of doing a modern Western was tossed around, which introduced the notion of setting Far Cry in Montana. A former Edmonton and Calgary resident, a mere 500 miles north of Montana, Hay was already familiar with the area and the climate, but the team flew in to explore the possibilities.

"We weren't sure at first, but within two days, we'd met enough interesting people, we'd been to enough interesting bars, we'd heard enough stories about people that wanted to live life the way they wanted... some people had actually moved to Montana to get away from the prying eyes of the government. There was this flavour, this feeling, and it felt very Far Cry."

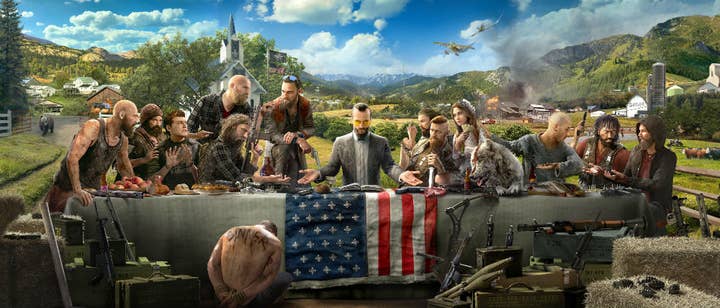

The bulk of the attention Far Cry 5 received around its announcement was the decision to pit players against a villainous, extremist cult. Even the signature art is somewhat provocative: a predominantly white, predominantly male group arranged in a scene reminiscent of Da Vinci's famous Last Supper mural.

"People are moving away from languages of 'us and we' and more towards 'us and them'. There seems to be a feeling that the global village is being pulled apart."

Shortly after launch, a Change.org petition called for Ubisoft to cancel the game, decrying the use of Christians and mainly caucasians as the enemies, as well as the American setting. While there are questions as to the validity of this petition, it's no stretch of the imagination that certain corners of the US may react in such a way.

But Hay stresses that the team has kept this as fictional as possible, instead focusing on the concept of cultism and how large groups of people can be lead astray by a determined but deranged central figure.

"We wanted to build this magnetic villain who has the ability to manipulate people," he explains. "The cult experts we were talking to were using words and a language I've never heard before. Some of these cults and leaders had almost built their own kind of language, talking about bliss and bliss-bombing people - it was strange. We realised we had something there but it had to be ours.

"For this one, I really wanted a villain that stood for something, that believed they were right and almost believed what they were doing was for the greater good. There was a layer of complexity that we wanted for the Father. He had to have a real belief, something that was bigger than everything, so we built a guy that absolutely believes the end of the world is coming, that we're all on the edge of a cliff and that when the end comes, will we really know it? His point, his belief, is that we won't know it. He's telling people to prepare for the worst because it's going to happen."

When the concept was first discussed around five years ago, Hay notes that it wouldn't have been quite believable to everyone because the world was a little more settled politically. So instead of real world events, the Father was based on the atmosphere Hay remembers from his childhood.

He talks about the fear that was mounting in the 1980s, towards the end of the Cold War. How ordinary civilians would watch the 'Powers That Be' try to avoid conflict, but were never able to escape the feeling that "we're really close to the edge". History, as Hay notes, has a tendency to repeat itself and our species finds itself approaching that edge once more.

"The truth of the matter is we have to remember it's a game. We're building an environment where players are going to express themselves."

"People are moving away from languages of 'us and we' and more towards 'us and them'," he says. "There seems to be a feeling that the global village is being pulled apart. It was interesting to have this character that really believes that.

"I was walking in downtown Toronto and a guy came round the corner wearing one of these sandwich boards, which said something to the effect of 'The End Is Nigh'. When I looked at him, I had two thoughts: one was, 'that guy knows something we don't, he's not crazy', and the second was, 'this is the first time I've ever looked at someone like that and thought they might be right - what does that say'. I took all of that, worked on it with the team, and that's how we built this guy who thinks the end is coming. We built our own cult around it, we built our own language around it."

Even the environment in which the game takes place is designed to explore a hypothetical situation, rather than make a statement on the real world. There is no Hope County outside of Far Cry 5, and that's how it should be.

"When you look at the themes and some of the things we're building, we really tried to make it feel like it was something that people could understand and that was believable for them," says Hay. "But we also focused on making sure that it's our [Ubisoft's] world.

"We had an opportunity to do a hyper-realistic game with a real location in Montana and real people, but we thought no, we want to be able to make it so that it's Hope. We built our own county, we built our own cult, their own belief system - but the trick to that is making sure you talk to experts, people who actually know this stuff."

He continues: "[The anti-cult message], it's a theme. It's a very potent elixir, but it's a spine. There's a lot of other meat and bone and sinew wrapped around that. The game still has to be fun, the opportunity to express yourself still has to be fun but it also needs to feel real in a way that if you meet a character or interact with them, they have beliefs. They're not just waiting around to give you a mission, and the world around them feels believable."

Herein lies the rub. Regardless of what anyone on the Montreal team would want to say with such an interactive exploration of cultism, Far Cry 5 still serves a very specific purpose: it is an entertainment product. Given the years and tens of thousands of dollars poured into it since 2014, Ubisoft still needs the game to appeal to the masses, the millions of console owners whose purchases will help fund Far Cry 6 (or whatever spin-off they move onto next).

But how difficult is it for Hay and his team to balance those two objectives: exploring their chosen themes and doing so in a way that offers more than lip service to the topic, but still creating a high-octane blockbuster that will sell to the mainstream?

"Obviously we want to build entertainment, and we want to make it so people can enjoy the experience, but it's okay to explore certain themes"

"It's really fucking hard," says Hay. "These games are huge and there's a lot of people working on them.

"The thing is when people discover a theme like this, they come to you and say 'well, your game has to be about this'. A couple weeks later, the world will change and they'll go, 'no, your game needs to be about this'. It's a really interesting thing to work on a game that people are so passionate about, and that has story elements that feel very now. But the truth of the matter is we have to remember it's a game. We're building an environment where players are going to express themselves.

"Where games are probably different from film and television, is that when you walk into a movie theatre or you sit down at home to watch a show, you're consuming. You're not necessarily an active participant in that. The verbs of your movement aren't there, it's more like just consumption. With games, we give you the controller and we want you to live it. We want you to author your own story - and that sounds super cheesy when I say, but it's true. We want you to be able to pick up the controller and go in any direction.

"Players are going to want to just go out and blow stuff up, or go and hunt, or just have crazy experiences with vehicles, to test the systems. Other people are going to want to have a very poignant moment with characters and be able to fall into the story and really let that wash over the top of them. We have to be able to make it so the world can react to that and that it's not one flavour. The danger of making something that's like that is you definitely don't want to be a buffet. You want to have real tastes, real opportunities and be able to curate your own experiences, which is very tough to do."

Even so, it's a promising step that a video game from the typically risk-averse AAA space is willing to explore something that, while it may not have been affecting as many people when the project was conceived, certainly does today. The indie space has delved into a myriad of sensitive topics for years, but we're still seeing very few major publishers touching on such topics in their biggest titles. Ubisoft is already an exception with the subject of racial profiling brought up in Watch Dogs 2, but again the need to sell a mass-market product compelled them to show restraint on how deep the team went.

The fear of deterring significant chunks of your audience by including something they disagree with is always going to be a problem for AAA publishers, but could we at least see more of those poignant moments Hay is so proud of?

"There's a nuance to this," Hay says. "There was a show I used to watch as a kid that did a very good job of touching on certain topics without beating you over the head with it - it was the Twilight Zone. They would tackle some really interesting conversations and different ideas, and they would explore different themes but they would do it using science fiction, using a little bit of reality but then they would shift and change so that you were touching on certain things without really realising you were doing it. It wasn't like 'this is what you have to know, this is what you have to think'. I didn't even realise it at the time.

"Obviously we want to build entertainment, and we want to make it so people can enjoy the experience, but it's okay to explore certain themes. Are we going to get to a place where some games only do that? It's hard to know, but what I like is that games have reached at point and they've matured enough to be able to explore things that movies and television have been able to do for 60 to 70 years.

"We've reached the point where it's not just go out and blow stuff up, it's not just go out and rampage somewhere. There are opportuities to meet characters, have relationships, be in a world that feels real, and put you in a moment where you're introspective and think about it - and then step out and have a completely different experience with a completely different tone. It's a cool time to be living."