Designing for accessibility from day one

Way of the Passive Fist developer Jason Canam explains why he had an accessibility consultant before a playable build

Household Games studio head Jason Canam had two inspirations in mind when he started making Way of the Passive Fist. The first, as he explained to GamesIndustry.biz recently, was the wave of 2D arcade brawlers from the mid-'90s, games like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Turtles In Time, The X-Men, and The Simpsons.

"I'm just a huge fan of brawlers as a genre," Canam said, adding, "They did a really good job of taking big, huge animated characters and making them into these awesome colorful and fun experiences. The game designer side of me really wanted to innovate because brawlers are kind of a stagnant genre. They haven't evolved much over time, outside of the odd game adding in a bit of RPG elements. It's really maintained a design status quo for 30-plus years, so I wanted to do something new."

The second inspiration was the fighting game genre, or perhaps one specific moment in the genre that has its own Wikipedia page. Known as EVO Moment #37, it's the conclusion of a Street Fighter III: Third Strike match at the 2004 EVO Championship Series tournament between Daigo Umehara and Justin Wong. Wong had Umehara down to a fraction of health when he triggered his character's Super Art, a flurry of more than a dozen attacks, any one of which would have finished off Umehara had they landed, or even been blocked.

"Daigo successfully parried and blocked the entire attack, which actually requires 14 1/60th-of-a-second inputs to do," Canam explained. "It requires 14 frame-perfect inputs. Adding in the fact that it was in front of 1,000 people in attendance, it was a very important moment. But it also instilled in me this idea that defense is more interesting than offense in fighting games. I think it's more cool to deflect or block a fireball with split-second accuracy than it is to throw the fireball itself."

The combination of those two influences yielded Way of the Passive Fist, a 2D brawler where the player verbs are more parry, dodge, and counter than punch, kick, and special attack. And while it owes a debt of inspiration to Moment 37, it's not looking to recreate that particular magic.

"All developers, I believe, are well-intentioned. And if you ask any one of them, they'll tell you, 'I definitely want as many people to play my game as possible...' But nobody thinks about it until the very end"

"Even though the game was inspired by these split-second, frame-perfect fighting game players, that wasn't really the game I wanted to make," Canam explained. "We still wanted to make something that everyone could really play."

That's a common sentiment in the games industry these days, but Canam went to greater lengths than usual to ensure the game really would be playable to everyone.

Way of the Passive Fist started production in the summer of 2016, around the same time as the Summer Games Done Quick speedrunning charity drive. One particular speedrun made an impression on Canam, that of Clint "Halfcoordinated" Lexa plowing through the indie Metroidvania-style game Momodora: Reverie Under the Moonlight on Insane difficulty in 31:58. The feat was all the more impressive considering that Lexa accomplished it one-handed due to hemiparesis that limits the use of his right hand.

"After his speedrun, he had the microphone for a couple extra minutes, and he mentioned how important it is for games to be accessible, and games that don't even do the bare minimum become completely unplayable for him," Canam recalled. "He had this plea to developers saying it's really important they do this, because there are many people in the audience you're leaving behind."

Inspired, Canam sought out Lexa and brought him on board Way of the Passive Fist to serve as a freelance consultant on accessibility.

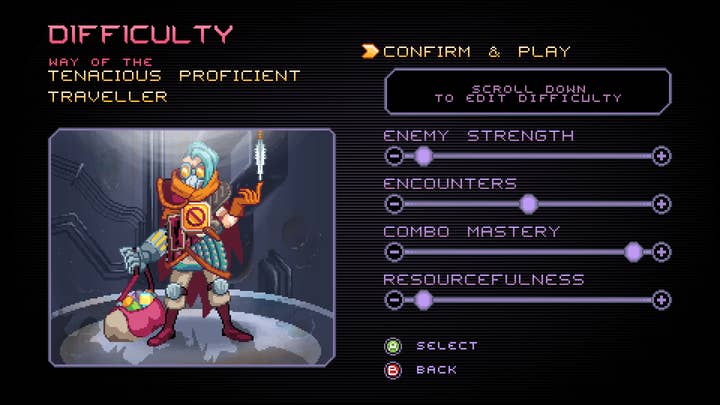

"At the beginning, we knew there were players with color-blind issues and different physical abilities who use controllers in unique ways, much like Halfcoordinated himself," Canam said. "But he mentioned to us an entire category we didn't really have on our radar, people with differing cognitive abilities, people with shortened reflexes, or delayed reflexes. So we were talking a bit about that, and that's kind of where our difficulty customization system came into place."

After players select a chapter of the game to play through, they are taken to a screen where they can adjust four sliders, each one controlling a different aspect of the game's difficulty. They can set how generous the timing windows are for counterattacks, how many enemies are on-screen at once, how strong the enemies are, and how frequent pickups and checkpoints are.

"That turned into a system that was accessibility minded in the beginning, but by the end it became something that was for everyone," Canam said. "Every single person that plays the game is going to be able to use this system."

For example, even players without accessibility concerns can appreciate the difference between playing the game with a horde of weak enemies and generous windows for counter-attacks compared to a playthrough with just a handful of over-powering enemies and scarce checkpoints.

The key for Canam was in bringing Lexa on board the project early. Household Games had a concept and design scope more or less figured out, but there wasn't even a playable build of the game ready when Lexa started consulting. While Canam admitted creators of all stripes might be reluctant to bring someone else into the creative process before the vision is formed, he said having Lexa's input throughout helped preclude any possible conflicts between what was best for the game and what was best for accessibility.

At present, Way of the Passive Fist's focus on accessibility makes a good hook for press coverage like this story, but Canam hopes it won't always be so. The only reason he sees for accessibility options not being the standard is simply a lack of awareness.

"It's something you don't always think about it," Canam acknowledged. "It's not always foremost in your mind. All developers, I believe, are well-intentioned. And if you ask any one of them, they'll tell you, 'I definitely want as many people to play my game as possible, just because the thought of someone not being able to is bad. It kinda breaks my heart.' But nobody thinks about it until the very end. Usually what happens is a team will spend a development cycle creating the game, and then at the very end go, 'Cool, let's have someone take a look at this.' Then when they get suggestions like, 'I can't do this part' or 'I had trouble with this part,' you're left with years' worth of work that you think, 'Well, we can't change it. It's too fundamental.'"

Canam is clearly an advocate of bringing consultants like Lexa on board early, but he said there are other resources developers can use to better consider the diverse needs of their audiences. For starters, the Able Games Foundation has a set of Game Accessibility Guidelines available on its Includification website. Written by developers in conjunction with gamers with disabilities, the guidelines detail a set of best practices to make games enjoyable for people with mobility, hearing, vision, and cognitive impairments.

Way of the Passive Fist is planned for an early 2018 release on PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and PC. PAX West attendees will also be able to try out the game and its accessibility features at the show's Indie Megabooth this coming weekend.