Isolation, depression "running rampant" among indies - Devolver co-founder

Mike Wilson on the state of indie development as he relaunches Gambitious as Good Shepherd Entertainment

Devolver co-founder Mike Wilson is on a mission to help indie developers put their best foot forward.

For the last five-plus years since Devolver shifted its focus to the indie scene, the company has looked at ways to help talented indies bring their games to market. One of those ways was to launch majority-owned Gambitious in 2011, a publishing platform dedicated to raising money for indies through investment and crowdfunding. Today, Wilson has revealed that Gambitious is rebranding as Good Shepherd Entertainment, and the publisher has also raised further capital while bringing on new executives.

Wilson will now be spending most of his work days as chief creative officer of Good Shepherd, while Brian Grigsby, another Devolver co-founder who's been serving as a management consultant, is now Good Shepherd's CEO. Gambitious president Paul Hanraets will serve as president and Ben Andac joins Good Shepherd as a business and product developer after years in product development at Sony Interactive Entertainment Europe.

While the exact amount of money raised has not been specified, representatives tell us that it's "by far the most in the history of the company." Ultimately, similar to Gambitious, Good Shepherd has a mission to bring new capital into indie games while "treating those new investors like heroes for trusting indie artists with their money instead of putting it into a mutual fund or an oil well."

If you're wondering how Good Shepherd will be different for indies than Devolver itself, Wilson explains to GamesIndustry.biz, "[Good Shepherd] is borrowing from Devolver's core philosophies as to how we treat and work with artists, but it is also different in that it is being carefully built to be able to scale, whereas Devolver is committed to staying smaller and laser-focused on what it is inarguably the industry's best at."

Good Shepherd is looking at a wide range of genres and budgets, but overall the focus is generally in the under $1 million budget range, or what Good Shepherd calls the "indies-that-seem-bigger" land. The publisher promises, "We don't take on any projects that we aren't prepared to invest a significant amount of capital and people to, as that model just isn't going to work anymore as the landscape continues to get more crowded and competitive."

"There are plenty of people out there selling pie-in-the-sky lottery tickets to the uninitiated investors; we do not wish to be a part of that"

Wilson continues, "Both companies look at any pitch as its own unique business opportunity, and have different tastes and metrics in deciding which ones to get behind. Even though Devolver is a major investor and supporter of Good Shepherd, the game submissions, greenlight processes, and publishing teams are completely discrete from one another.

"Good Shepherd, like anyone competing in the indie publishing space, has its work cut out in establishing ourselves as force to be reckoned with, but we do have the benefit of the track record at Gambitious, which even without a lot of funding or people resources has consistently found profitability in a very crowded, rapidly evolving marketplace, without any breakout franchise hits.

We've been patiently, methodically building a strong publishing machine over the past few years to be able to produce these results that work for more and more types of up-and-coming developers and games, and we've now filled in some gaps with some very experienced and talented new people joining the team. We're terribly excited to see how much better we can do with this great lineup of games and this team."

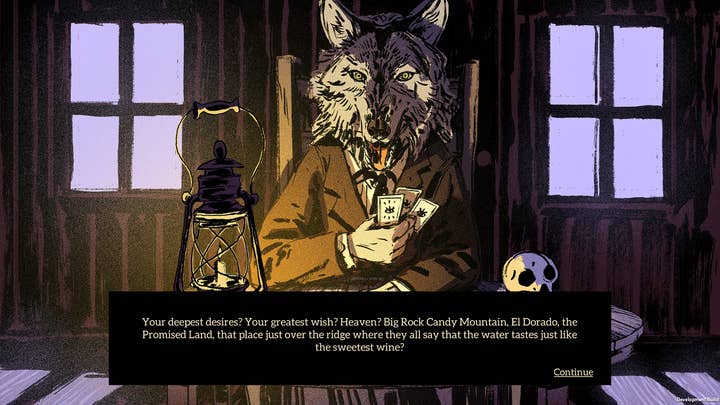

Gambitious' previously announced titles - Milanoir, MachiaVillain, and Outreach - are now slated to be released under the Good Shepherd name. Nothing will change in terms of support for those developers and their projects. Furthermore, Good Shepherd's first original signings include Dim Bulb Games and Serenity Forge's Where the Water Tastes Like Wine, and Phantom Doctrine, which the company says is its most ambitious project yet.

As you might expect with a Devolver-backed company, Good Shepherd will "work to keep the IP in the hands of the creators, and keep ultimate creative freedoms and decisions in their hands, as these are their babies," says Wilson.

"As for the business model and deal structure, it's built around the way we've always done business with our various companies... very artist-driven and the developers always keep creative control and the lion's share of the profits. We provide whatever funding is needed for a project that we greenlight, and we guarantee the full amount of funding needed to effectively produce, market, and publish the project globally (it's not contingent on any investor raise).

The only difference is that in the background, as we grow our private investor network, we sell off some of the risk on each project in return for profit participation, so that we can offer such deals to more and more indie developers."

While Good Shepherd is willing to look at anything, its primary focus (at least for now) is on PC and digital console marketplaces. The company has not yet waded into the somewhat risky pools of mobile F2P and virtual reality, but nothing is ruled out.

"Because we are so concerned with providing new investors and developers with a positive experience, we do tend to be pretty fiscally conservative," Wilson notes. "There are plenty of people out there selling pie-in-the-sky lottery tickets to the uninitiated investors; we do not wish to be a part of that."

While Gambitious had opened the first major crowdfunding platform for video game development back in 2012, one major difference for Good Shepherd is that it's actually not focused on crowdfunding.

"Even with some of the most successful teams we've worked with, isolation and depression are running rampant among indie creators... Gamers can be a notoriously rough bunch to deal with online"

"We are not engaged in crowdfunding, but are rather trying to learn from and correct the mistakes that have plagued it, which have resulted from poor management of initial scope and budgeting, sloppy production, and we feel, ultimately, a lack of respect for people's hard-earned money," Wilson says.

"There is indeed a lot of support and interest out there for more and more great games to be made, especially in niche areas that the larger mainstream publishers can't justify, but treating this interest as a dumb-money gold rush has been incredibly short-sighted for those who truly care about this sector of the industry. And while we realize that most of these mistakes and disappointments have been unintentional, as experienced investors and publishers, we knew from the beginning that this would likely be the case and that is largely why this company started in the first place."

One of the big challenges nowadays for any small studio is tackling the ever-present issue of discoverability. Wilson is fully aware of how hard it can be on indies look to get noticed in overcrowded marketplaces.

"We find it highly advantageous to remain small and nimble, not only willing, but eager to anticipate and react to the ever-changing landscape," he says. "We keep our eyes open and our risks calculated, leveraging the vast experience and strong relationships of the team. The developers we work with are constantly adjusting their sights and expectations regarding different platforms as well... it's honestly all very exciting and invigorating compared to the more predictable past or the somewhat stale nature of the bigger side of the business."

Beyond the task of getting people to actually buy an indie game, Wilson remarks that he's seen too many developers forget to take care of their own needs as human beings. That's something he hopes to help with at Good Shepherd as well.

"Honestly my biggest concern with indies is that they learn how to take care of themselves," he says. "Even with some of the most successful teams we've worked with, isolation and depression are running rampant among indie creators, with ever-increasing competition for attention and the unprecedented access to the artists that their critics (who is now everyone with an internet connection) now have. Gamers can be a notoriously rough bunch to deal with online, but with these small teams and the consistent demand that they interact directly with their 'community,' things have become much harder to manage, and very very personal.

"This is something Good Shepherd is committed to working to figure out how to best address, as we've seen the problem up close and personal with both Gambitious and Devolver in recent years, and it matters deeply to us. These people are our friends, and we want them to be able to live healthy, happy lives doing what they love to do. We're not sure that this is a problem we can solve, but we are very eager to start the larger conversation."

"The fact that you don't need a hardcore programmer or a $500,000 game engine to make something now has opened the market up to a huge range of new creators"

Taking a closer look at the indie scene, it's readily apparent that one of the major reasons for overcrowding has been the democratization of development through free and easily accessible tools. Almost anyone can make a game today. And while that has certainly complicated the indie scene, Wilson wouldn't have it any other way.

"The fact that you don't need a hardcore programmer or a $500,000 game engine to make something now has opened the market up to a huge range of new creators, similar to what has happened in the indie filmmaking world," he says. "But, on the whole, this is a very positive thing, and it's what has kept it interesting.

"If the games were being made by the same types of people and companies who have been making them for the past 40 years, that wouldn't be very interesting at all. Comfortable, perhaps, for the insiders, but stale. This is the best time in the industry since I've been in it, and as long as indies remove themselves from dreams of the 'mainstream' and focus on making what they passionately want to make, the tools for finding an audience eager to support your efforts are more accessible than ever. But having a solid publishing team working with you certainly helps."

Indeed, under the right terms, publishers can be quite beneficial for indies, and that's where Wilson hopes Good Shepherd comes in.

"We are interested in making the indie market sustainable for a wide range of artists to survive and thrive in," he says. "We aren't interested in bubbles, or apocalypses, but the renaissance is real and exciting. Our great hope for Good Shepherd is to be a benevolent force in the industry that helps prove that there is a great business here still, for those willing to roll with the change and embrace it."