Students of Many Forms

How the National Film and Television School is shaping the future of the UK's games industry

I've missed the bloody spaceship.

By the time I arrive, through weak snow on a bleak February morning, it's already departed - stripped down to component parts and taken away so that the soundstage it previously occupied can be redecorated and turned into something else. It might eventually be a pirate ship, or a 17th century shepherd's croft, or a run down blues bar in New Orleans, or even a different spaceship - things change quickly on the campus here.

It's a slightly incongruous setting. Situated in the decidedly conventional town of Beaconsfield to the north west of London, the National Film and Television School is a charming hodgepodge of buildings new and old, some dating back as far as the 1920s (the first ever 'talkie' film recorded in the UK was shot here) and some as new as two months. It's a busting labyrinth of cameras, recording booths, lecture halls and giant, glistening mixing desks - with the microcosmic worlds of stop-motion animation sets sitting alongside rooms of motion capture equipment. Every door opens into a workshop of a different discipline, and one of the newest is games.

The NFTS has been running a games course for around five years now, and the focus has always been on interdisciplinary education. Students on the masters course here will be paired with directors, sound engineers, cinematographers and writers on some of the most well-respected courses of their kinds in the country, working together on joint projects which bleed techniques across mediums and forge new collaborations.

This sort of integrated approach has been a keystone of the course since its inception in 2012, but newly appointed acting Head of Games Alan Thorn has made collaboration the watchword of the programme, bringing together not just students from different departments, but bringing in industry legends from TV and cinema, like last month's visitor, Roger Deakins, to contribute to the work the students are producing. In addition, a raft of games luminaries such as Siobhan Reddy, Imre Jele, Tara Saunders, Andrew Oliver, Richard Lemarchand, Barry Mead, Mike Bithell and Jess Curry have contributed their knowledge to the course.

From what I see of the projects on offer, it's certainly producing results, and the integration of the crafts of storytelling, cinematography and high-end audio production are very much apparent in the games being worked on in the classrooms here - a fantastically healthy sign for an industry which is rapidly embracing new forms of expression. Thorn says that his students represent a wide range of backgrounds and ambitions.

"In terms of the background of experience for students, it's completely varied"

Alan Thorn: Acting Head of Games

"In terms of the background of experience for students, it's completely varied," he explains. "Some of them may have a background in games, some of them may even have been developers themselves in a previous career, but some come from a completely different walk of life. They had a great idea, they're really enthusiastic about games, so they apply themselves and adapt to a new medium.

"In the first year, every module we have is designed to not only allow them to create a game project, but to learn the skills and tools necessary incrementally as they go. So they could come from a background with no experience and the modules are tuned to introduce skills. The first module, Hello World, teaches them how to model and build 3D environments, then they move on to a bit of coding, so everyone can build up a portfolio.

"There are many ways in which the games course is already so integrated with the other modules taking place here, even in the short time we've been here we've produced some really great output. Information also flows the other way. For instance, we've had a lot of sound designers who have been really interested in how we implement sound within a game, what the tools and techniques are. We also see a lot of writers who are looking for inspiration from branching narratives in games, looking at how to write for that interactivity, so we get a lot of involvement the other way as well."

I'm joined on the tour of the studio by someone who knows exactly how the industry works: long-term NFTS board member Phil Harrison. He agrees that the exposure to talented people working in other creative industries is a fantastic driver for success.

"One of the exciting things about the school and the relationships created here is that they will potentially continue after the graduates walk out of the gates and into the world of work. Lots of these people are working in a freelance capacity and you can imagine them joining up to form companies or more temporary business relationships. I think that's a very powerful part of what this school provides.

"A lot of people think about these disciplines being very vertical, screenwriting, directing, TV, games; but actually the students here see them as being very horizontal, and I think that's how we should look at them as well"

Phil Harrison

"A lot of people think about these disciplines being very vertical, screenwriting, directing, TV, games; but actually the students here see them as being very horizontal, and I think that's how we should look at them as well. Hopefully that relationship will grow even closer."

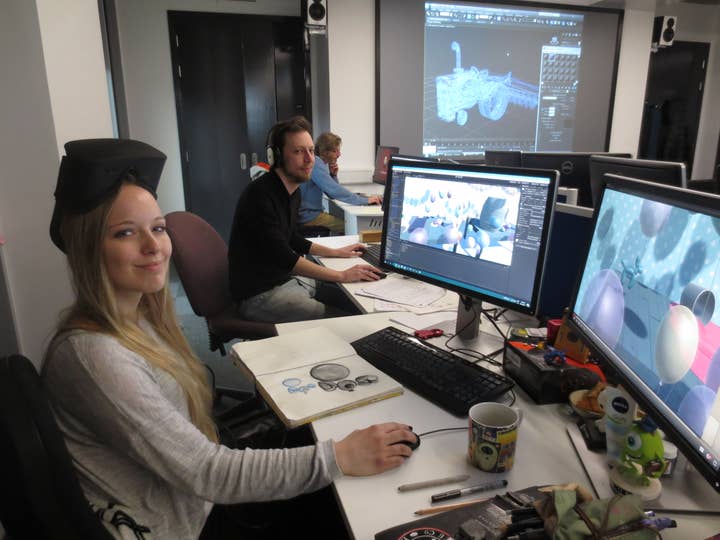

The labs we're sitting in are brand new, completed in December and completely dedicated to the games course, doubling the faculty's teaching space. There are students working on projects on PC, tablet and VR, and the breadth of the course is impressive. Of course, sometimes too much scope can be an issue, so I ask Thorn why he takes this approach rather than one with a tighter focus on specifics like physics or particular coding languages - after all, one of the criticisms levelled at previous generalised game development courses has been that they produce Jacks of all trades who struggle to specialise.

"One of the ways in which we address that is that the student can identify where they want to go and how they want to position themselves in the industry," he answers. "Because there are ten students in the first year group, for example, they get a lot of one-to-one tutor time, which allows the specialised tutors to focus on their subjects and develop the students' skillsets so that if they want to position their portfolio as a coder, or artist, or animator, they can do that.

"They have a lot of creative freedom on what the project is about, so they can often tailor that project to focus on whatever particular aspect they'd like to shine. In the first year, every project is in a different medium. The very first game they pursue is PC, then it's tablet, then the next game will be VR. So we try to encourage them so that by the end of the first year they've experienced a lot of different mediums, then when they approach their second year project they can decide which one they want to focus on. They might be particularly enthusiastic about a particular medium, and we'll ask them what their justification for that is. They'll all have a different case, and I think it's very important that we encourage a wide variety, including VR and other emerging technologies."

"I'll give you a perspective from the commercial world," adds Harrison. "Although an eight-year physics expert is very important for the industry, what's great about the graduates that come out of here is that they've 'shipped' at least one or two pieces of work, so they know what it's like to start, develop and finish - and often the crucial word is finish - several pieces of work. So they understand all of the phases of the development process. Maybe not to AAA scale, but they know the process, and I think that's incredibly valuable."

Although I miss the spaceship, I do manage to time my visit to coincide with another rarefied visitor - Digital and Culture Minister Matthew Hancock. Harrison assures me that Hancock will see the games students at work and that the school sees the cultural ambassador role as very much a part of its remit.

"That was one of the reasons I got involved on the board of the school five years ago," Harrison says. "The games course had just started and I was very excited by all of the possibilities. But what the management of the school should take credit for is that they've totally changed the way this institution is funded, and the way that higher education establishments are funded by the mechanisms of government.

"Without getting into the nitty gritty of that, that means that this place is now funded to a greater degree than it ever was in the past. You're sitting in the most recent physical manifestation of that, but it's also shown in the way that the MA courses are taught, the quality of the teachers, the visiting tutors. That's happened without games becoming a science project; it's actually been integrated into what the school stands for. We can always do better at that, but I think we've made incredible strides forward.

"When I was at Sony in the UK, pretty much every university and college was starting its own games course. We thought we'd better check them out, so we had one of our executives go out and validate all of those courses. Not one of them passed. None of them, we felt, were fit for purpose. They did not align with the needs of the industry and none of them really did a good service to students.

"Clearly that has changed, not just here but across the UK and the world. Film schools have been around for 40-50 years, games schools much less. They've got a lot to catch up on, but the progress has been dramatic. With the rate of change of technology in games being at a far higher frequency than film or TV, which are relatively stable, the gap is going to be closed very quickly."