"It's always extremely scary to call someone out"

Tinybuild's Alex Nichiporchik on taking G2A to task, battling piracy with aggressive pricing, and the "magic tricks" required for indie success

Earlier this week, Tinybuild CEO Alex Nichiporchik called copycat. There were glaring similarities, he said, between N-Dream's browser game Runorama and Speedrunners, the sleeper hit that helped to establish Tinybuild as a rising force in indie publishing. Nichiporchik issued a copyright takedown, and explained his reasoning in a typically candid blog post.

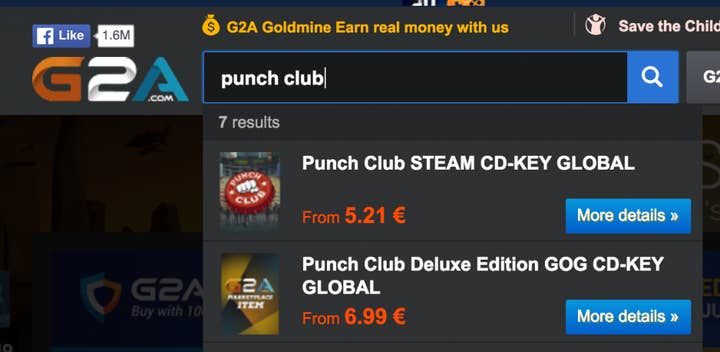

This isn't the first time Nichiporchik has felt moved to speak out in this manner. Copycat design is just one of many issues that indie developers face in this ultra-competitive industry, and Tinybuild is clearly unafraid to meet those issues head on. In June this year, Nichiporchik did just that with G2A, a popular online marketplace for the resale of Steam keys, which had hosted around 25,000 sales of Tinybuild games for some $200,000. Much of this money had come from keys purchased with stolen credit cards, Nichiporchik said, meaning that not only was not a single dollar making it back to the developer, but the developer was also being hit with chargebacks when the fraud was discovered. A lack of even the most basic checks meant that G2A's model was, to use Nichiporchik's description, "[facilitating] a black market economy."

"We bought pirated games... It's part of my past, and I get where the people that drive the economies of these key resellers come from"

"This industry is very small, so it's always extremely scary to call someone out," Nichiporchik says, several months on. "It might backfire. You might say something incorrect. Or what if you're actually wrong? The reason we had to call [G2A] out is because they supplied us with the data, and then said they wouldn't pay."

Nichiporchik has no regrets over highlighting the problem, but he claims to be less than satisfied with the way the situation played out. The week following the publication of that initial blog post was a flurry of statements from both sides, what Nichiporchik describes as a "political-ish press release fight." Tinybuild's stance had an impact - certain YouTubers backed out of sponsorship deals, and Humble Bundle reiterated its own policies around fraudulent transactions - but G2A's own response fell short of what Nichiporchik believed the situation demanded.

"They have the install base," he says. "It's huge, and they're making a ton of money. The only way I feel they can fix this is by coming out in the open and saying, 'Here's a problem. We're going to shut it all down, we're going to become a legit store, we're going to partner with all of these legitimate companies, and everything is going to be great.'

"They never acknowledged the facilitation of the grey market economy. They just said, 'Yeah, hey, it can happen.' I wasn't happy with that at all. It did move a little in the right direction when they announced their developer program, where you can get 10% of the sales.

But I'm like, 'You can get 10% of the sale of stolen goods?' It's like becoming a partner in crime."

"Essentially, in this industry you need to do magic tricks... We have to do something different, and each time it gets more and more difficult"

It seems unlikely that G2A will ever retreat so far from its established business model, but even if it did the problem would surely resurface elsewhere. To a certain extent, a marketplace where game keys are resold at substantially below the going rate - Tinybuild estimates that the $200,000 in G2A sales would have earned $450,000 at the prices it set on Steam - is legitimised by consumers, who are content to take the better deal without spending too much time thinking about how that price is reached, or whether the money end up in the pocket of the game's creator. A G2A reshaped in the way Nichiporchik describes may not be able to offer that same low price, leaving the door open for another marketplace that can.

Nichiporchik is adamant that the price of games should be no lower than can be achieved by legal means, but he also acknowledges that there are consumers who will use a service like G2A to avoid being priced out of the market. Indeed, growing up in Latvia, Nichiporchik was one of them.

"I was in a similar situation. I had no money to buy legitimate games," he says. "The average salary in my country was $120 a month. There was no way. We bought pirated games, I fully admit. It's part of my past, and I get where the people that drive the economies of these key resellers come from."

The emphasis for developers, he says, should be to ensure that those people aren't alienated from legitimate commerce. If the alternative is that a given user turns to piracy or the black market, then even a single dollar earned still represents a profit where none would exist otherwise. Nichiporchik advocates "more aggressive regional pricing" among indie developers, where even neighbouring countries are treated as distinct business opportunities. "Just make it super easy to make a snap decision," he says. "In the example of G2A, if your game at the discount rate for someone from Russia costs half of the MSRP in the US, make it that... If so many people are pirating your game, the odds are that you can play with pricing, make it more aggressive. Or make it so there's more value in buying the game."

On this last point, Nichiporchik offers the example of Speedrunners, the first game Tinybuild worked on following its debut release, No Time To Explain. At its core, Speedrunners is a multiplayer experience, one tied to Steam and Steam matchmaking. "You can't really enjoy the game if you pirate it," he says, but it was still possible to play pirated versions of the game locally. "We decided to just give away the local version for free anyway. Like, 'If you're still going to pirate it, here you go.'

"Developers need someone on their team, someone who can take it all and make it into a simple to understand, interesting story"

"The way you need to look at this is, 'You should buy my game because...'"

Of course, there is a great deal more to Tinybuild than its forthright, constructive responses to adversity. When I saw Nichiporchik speak at DICE Europe earlier this year, it was abundantly clear that the company's success was down to an enviable knack for identifying emerging trends before the patch of ocean had turned from blue to red. No Time To Explain was among the first games to be successfully funded on Kickstarter way back in 2011, for example, and it was in the second wave of games to be Greenlit on Steam. The decidedly mediocre reviews it eventually received did little to harm sales thanks to the influence of an emerging media form known as the "Let's Play" video, while Speedrunners rose to success with help from videos made by a rising YouTube star called PewDiePie. Since then, the company has made ingenious use of Twitch to draw attention to games like Party Hard and Punch Club.

If there is a common thread that unites Tinybuild's successes, it's the acceptance that, in today's indie game market, any novel strategy will be imitated dozens of times before you have the chance to try it again. The unifying idea is to move on before a given tactic grows stale. "We don't really have a product strategy per se," he adds. "It's more like, 'Okay, the game is fun. How can we sell it?' What was relevant six months ago might not be relevant today.

"Essentially, in this industry you need to do magic tricks. We did a magic trick with Party Hard, and we can't do it again. If we have a game with Twitch integration, now every goddamn game has Twitch integration. We can't do Twitch Plays Punch Club twice. Twitch right now is relevant, livestreaming is relevant, but each time with each game launch it's not like there's a set template. We have to do something different, and each time it gets more and more difficult.

"What we've noticed in the past year is that, after doing so many 'stunts', we have a reputation for that. So at the very least we have a slight advantage among other indies with our brand."

Those commercial smarts counterbalance the company's more confrontational side - an increasingly important aspect of the same brand. Like most people, Nichiporchik is happy to talk about Tinybuild's triumphs, but there is no reluctance to confront its mistakes or expose uncomfortable truths. "I think development culture needs to become a little bit more open," he says. "People like to talk about what was successful and ignore what didn't succeed. It just needs to be more interesting as a story.

"I used to be a games journalist, and what you're doing here is trying to make a story out of all of these bits and pieces. Developers need someone on their team, someone who can take it all and make it into a simple to understand, interesting story. It's about what you say, but it's also about how you say it."

GamesIndustry.biz is a media partner for DICE Europe. Our travel and accommodation costs were provided by the organiser.