Flying solo: Surviving as a one-person indie

Gambrinous' Colm Larkin and Versus Evil's Steve Escalante reflect on the hurdles individual developers face in today's increasingly competitive market

The rise of the indie games market over the past decade has taken the industry back to its roots: lone creatives building games from their bedroom, garage, kitchen table, and so on.

But with absolutely anyone now able to develop their own titles, the work required to release and maintain a best-seller can be incredibly daunting - particularly as the chances of success seem to be falling.

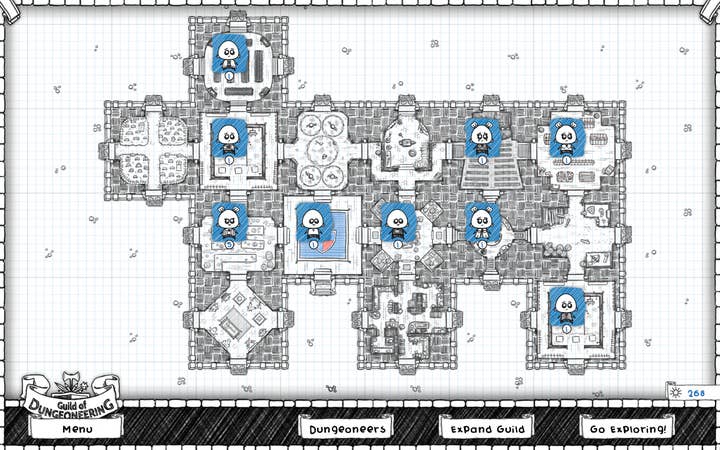

For every $10m global hit like The Escapists, there are countless games that never reached the audience their developers hoped for. It's a disheartening market to be in, but Colm Larkin - the man behind one-person studio Gambrinous and creator of turn-based RPG Guild of Dungeoneering - urges his fellow developers not to give up hope.

"Success as a one-person developer is definitely possible," he tells GamesIndustry.biz. "Look at how Undertale and Stardew Valley saw massive success in the last year from one-person indies. Your fans don't care about big-budget marketing campaigns or expensive production values. Yes, you need to work hard and invest time to reach people, but it is not impossible or a lottery."

However, Steve Escalante - general manager at Dungeoneering's publisher Versus Evil - stresses that the sales and revenue generated by the likes of The Escapists or Stardew Valley are still the exception, not the rule. So while success is indeed still possible, it depends on what you qualify as success.

"Some games might not make $10m or more, but they can still be seen as a success at $2m," he says. "Those are also big wins. The developer has had a successful launch, begun growing a community, delivered on their vision and promises, and now has a brand they can nurture."

"Marketing is one of the most important things you need to do. Focusing entirely on making a great game and hoping people notice it is a mistake. Hope is not a strategy."

Colm Larkin, Gambrinous

Even $1m or $500,000 can be a major success for an individual developer if it's enough to recoup costs and potentially fund future projects. Herein lies a key advantage of being a one-person or even reasonably small studio: little to no overheard. Two people with no office will have significantly fewer monthly expenses than a team of ten, which would still be small for a studio today.

As much as funding your next game with your most recent release can appear to be a highly sustainable business model, Larkin reminds developers that it is not essential given where most one-person studios begin.

"Most of us start out by developing on a shoestring and making the absolute most of very little," says Larkin. "No indies start out with a pile of money. If your game does well enough to fund future work, fantastic. If not, you can still fall back to developing on a shoestring - with the added advantage of a record of finishing games under your belt.

"Then there's the creative freedom. You are free to make something completely different to the kind of safe bets the bigger companies are working on. You can be experimental with art style, genre, mechanics, even marketing. You have little to lose and so much to gain in terms of standing out."

Of course, it's crucial to keep in mind that as a one-person developer, absolutely everything falls under your care. Are you prepared for that challenge?

"If you are testing your game, then you are not technically developing your game," Escalante observes. "If you get sick then engineering, art, sound and production team are out of commission. Having to create all aspects of the game adds some pretty significant stress, although some might also call this freedom.

"But you need to remember that you are reliant on the programmer to get your art in, that's you. Or the artist to get those animations fixed, also you. And if the sound just isn't right? That's you. Did I mention the UI is borked? You."

Larkin adds: "There is never enough time to do everything and it is hard to focus on any one aspect of the game when you are responsible for all of them. While I started out by myself, I formed a team of five to finish Guild of Dungeoneering.

"The gaming landscape has changed quite a lot in the last five years. It's easier than ever to get your game into the hands of players thanks to things like Steam Greenlight, but a little harder to stand out because of this. Making a hit game was never easy, and that hasn't changed, but I think some of the barriers to entry have been removed and that helps the tiny indies a lot."

"You don't have the millions in dollars of marketing, but fun is hard to create. Remembering that a smaller team can make a lot less money to be successful is important."

Steve Escalante, Gambrinous

Escalante agrees, adding that a combination of new routes to market plus the democratisation of technology like Unity and Unreal - making it possible for indies to produce titles that historically required much larger teams - means there is now "a tremendous amount of content" out there to contend with.

"Discovery is a huge issue," he says. "It used to be just for mobile, but now has certainly revealed itself on platforms such as Steam. Developers need to create strong fanbases and gather industry contacts to enlist the help when they can. Working towards a communication and content plan to stay in contact with your customers is going to be more and more important as time goes on."

This emphasises another pressure one-person indies can face on top of all the other responsibilities they have: marketing. There has been plenty of talk over the past few years about how important self-promotion can be, both for your games and yourself as a developer, but Larkin says the value of this task cannot be understated.

"Marketing your game is one of the most important things you need to do if you want to be successful," he says. "Focusing entirely on making a great game and hoping people notice it is a mistake. Hope is not a strategy.

"The gaming landscape has changed quite a lot in the last five years. It's easier than ever to get your game into the hands of players, but harder to stand out. "

Colm Larkin, Gambrinous

"What worked for me was developing a create-share-feedback loop. I developed in the open, sharing a playable version of the game from day one. This let me slowly build up a following, sell some early pre-orders, and generally validate my idea and keep my motivation up. Over time this built the foundations of the game's fanbase."

Escalante adds that the thriving digital ecosystem is also changing how players enjoy their games, and therefore how they need to be approached: "Today's customers consume content at a rate we never would have predicted. Because of this, you need to be willing to share, get people involved and provide a platform to communicate. It doesn't have to be fancy, just a simple website or a social-web-app triangle that all works. Either way, engaging and re-engaging is key. Going silent is a huge drag on momentum.

"If your game is fun you can compete. You don't have the millions in dollars of marketing, but fun is hard to create. Remembering that a smaller team can make a lot less money to be successful is important."

Another valuable development when it comes to how one-man studios can promote their game is the emergence of streamers. Platforms such as Twitch now command so much attention that it is shifting the way people experience games they may consider purchasing.

"It's important to think about how people will play your game - often in front of an audience - and what you can do to in your game to take advantage of that," says Larkin.

"That's something to consider for your next game: think about how streamers will play it and what you can do for them. It needn't be that complicated. One simple thing we added to Guild of Dungeoneering was the ability to rename your heroes, and we saw it again and again used in live streams to name them after viewers. Easy to do and hugely more interactive for streamers and viewers alike."

The Gambrinous founder's final advice is that just as one-man indies should keep their standards of success in check, so too must they reign in their expectations of what they can accomplish alone.

"Make smaller games first," he suggests. "Don't focus on your dream game as your first release. Try and get used to finishing projects - game jams are great for this. Share your work, and build up from there. I made a whole load of tiny games before getting the confidence to make Guild of Dungeoneering and it made all the difference."