Tiger Style: A tale of two Spiders

Six years is a long time in mobile gaming. For Randy Smith, it meant the difference between success and failure

Free-to-play is now the dominant model in mobile gaming, and to such an extent that it's easy to forget the velocity of its rise. If you take the launch of the App Store as a starting point, free-to-play monetisation techniques went from nowhere to ubiquity in the space of just seven years. But that's only if you trace a line from 2009 to this very moment. In truth, any reasonable doubt that premium priced games would be overwhelmed disappeared years ago - two, three, some might argue even more.

When Randy Smith founded Tiger Style Games in 2008, though, what now seems inevitable was still mysterious. It was the year of Braid, Castle Crashers and World of Goo, the whole industry was on the verge of huge but essentially unknowable changes. "The concepts from traditional games were still basically what defined the medium," Smith recalls. "It was like Deus Ex or Minesweeper, Quake or Solitaire."

That Smith mentions Deus Ex in this context is telling. His first job in the industry was at Looking Glass Studios, where he stayed for three years, and his second was at Ion Storm Austin, where he stayed for five. During that period, Smith contributed to System Shock 2, three entries in the Thief series, and he was working for Ion Storm when Deus Ex was first published. It was a seminal period in the evolution of games as an expressive medium, helping to define and set the expectations of core gamers for years to come.

"There was an idea - and this was revolutionary at that time - that eventually you'd be able to sell a game on a mobile platform for $10 or even $20"

Though it may not have seemed so in the moment, the closure of Ion Storm Austin in 2005 was well timed. It afforded Smith the opportunity to take stock and explore his options, and when the iPhone launched in 2007, the best option became immediately apparent. "It had all these features," he recalls. "It was a totally viable gaming platform, but you had to think about it as itself."

Many of Smith's peers had the same thought, including Looking Glass co-founder Paul Neurath, who was working on a pirate-themed mobile MMO at his new company, Floodgate Entertainment. Smith describes it as, "a real solid game design," but it was also clearly intended for gamers on more traditional platforms. "The only difference was in the play patterns," he says. "You'd only play it for two minutes, and not two hours."

When Smith co-founded Tiger Style with fellow Ion Storm veteran David Kalina, they agreed to depart even further from the tropes and concepts that had defined the medium before. "I believed in the idea that you could make good video games for any format. That's where we started with Spider," Smith says. "We honestly weren't sure what would happen. I knew that there would be an audience who would understand it, but I didn't know that it would come to be regarded as one of the games that proved you could be a 'good' mobile developer."

That claim isn't braggadocio on Smith's part, either. Spider: The Secret of Bryce Manor, Tiger Style's debut, marked the point at which many critics changed their minds about the worth of mobile games. It was the first post-iPhone mobile game to be reviewed in the venerable Edge magazine, and the same was true of the magazine to which I contributed. I can vividly recall the confusion with which we regarded the unruly growth of mobile gaming, desperately searching for a sensible way to cover the maelstrom of new products. Smith recalls it, too.

"The reason the press wasn't covering the App Store was that there were a shitload of games, but they were mostly hobbyist games and companies trying to figure out how to capitalise on the market," he says. "There was a lot of squiggly line games, stick-figure fighting, a lot of 99 cent games that might eventually profit.

"That was really where the App Store was going; it was kinda like the dregs, but it was interesting because it was people experimenting who weren't from traditional games."

Spider was different, displaying the kind of smart design choices one might associate with developers from Looking Glass and Ion Storm, but still entirely suited to the iPhone's form and features. Tiger Style launched it in the second half of 2009 with little fanfare and scarcely a dollar spent on marketing, but word of mouth and (for a mobile game) unprecedented coverage from the enthusiast press drove it to success. At that point in time, it seemed like an edifying glimpse of what was to come from the App Store, and mobile in general; a market where talented developers could pursue smaller, creative ideas away from the escalating budgets and myriad compromises of legacy platforms, and with a large enough audience to make good returns by charging just a few dollars.

"There was an idea - and this was revolutionary at that time - that eventually you'd be able to sell a game on a mobile platform for $10 or even $20. Mind-blowing," Smith says. "We were reluctant to sell Spider for $3, because we were former AAA developers, and video games cost $60.

"I didn't know it would be a race to the bottom where you'd need to sell your game for pennies - not even 99 cents, but microtransactions"

"What I did know, and we talked about this when we started Tiger Style, is that eventually the big players with a lot of money and business acumen and communications departments at their disposal were gonna come along and colonise [mobile games]. They were going to write the rulebook about how you made money in the space. I didn't know what form that would take. I didn't know it would be a race to the bottom where you'd need to sell your game for pennies - not even 99 cents, but microtransactions.

"I didn't know that's how it was going to be. In fact, a lot of people didn't."

Tiger Style's second game, Waking Mars, received the same high level of critical praise, and though its audience built more slowly it performed almost as well at market. So when the notion of making a sequel to Spider arose in late 2012, the nerves that had set in on the previous two games were largely absent. "We learned from those games that things can work out for us," Smith says. "We already knew Spider was a hit. It won game of the year awards and made tons of money for us. So we thought, 'Great, even if Spider 2 isn't going to hit a sweetspot in the zeitgeist this time, it's a stable bet. It may not be a strong bet, but it's a stable bet.' I was a lot less nervous about it this time."

The approach to Spider 2 included many of the best practices involved in creating a sequel to a packaged console game: bigger, deeper, more beautiful, more fleshed out, all of which seemed to fit with the direction the mobile market was heading at that time. From being one of the prime movers on the App Store, Tiger Style had seen budgets rise and companies like Rovio - effectively AAA mobile developers - ascend to the summit of the market. "We were walking our way back to AAA from these very minimal concepts," Smith says, "and so our thought was to do that: we're going to polish and make this big, great thing."

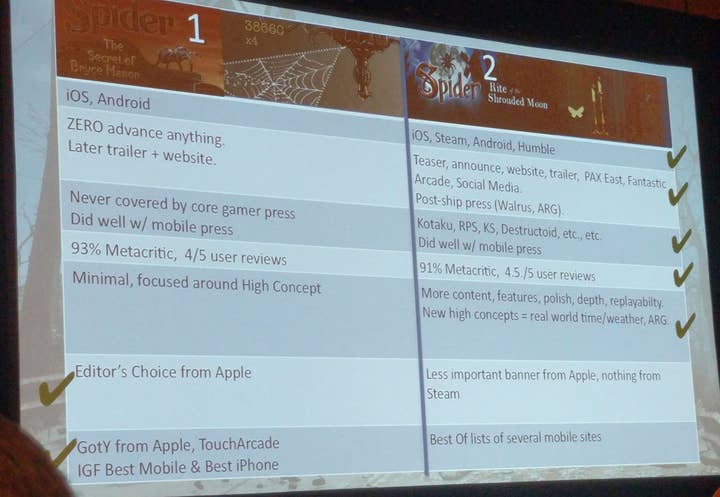

At GDC, Smith gave a talk on the difference between the launch of Spider and the sequel, Spider: Rite of the Shrouded Moon, which launched last year. The slide below summarised those differences, lending credence to Tiger Style's assessment that Spider 2 was a "stable bet."

The outcome, though, was very different. Despite spending more time and more money, despite applying an actual marketing strategy, despite getting excellent reviews from a wider range of press outlets, and despite the pre-existing reputation of the first game, Spider: Rite of the Shrouded Moon earned just $13,000 in revenue per person year. By contrast, its predecessor earned $500,000 per person year. In his GDC session, Smith described this "very unsustainable" return on investment as Tiger Style's first sense that, "there might be such a thing as the Indiepocalypse."

"If we had the idea for Waking Mars today I don't think we would release it. Doing so in this market would be an act of charity on our part"

When Tiger Style looked at the mobile market back in 2012/13, it made a judgement that, "everything was getting bigger and better." Given how Spider 2 performed commercially Smith has little choice but to accept that judgement as incorrect, but the reality cannot be so neatly divided into right and wrong. Mobile games have indeed become bigger, but to such a suffocating extent that the leading IPs (Clash of Clans, Candy Crush, etc) have effectively become genres unto themselves. Spider 2 made a play on the usually winning combination of quality and familiarity, but the ceaseless flow of new product means that even arbiters of taste within the press can no longer have an effect on a single game's fortunes.

Smith could be forgiven some reluctance in once again trying to predict the direction of mobile market from here, but he's clear on one thing: as an indie, "offering a feast to your audience doesn't work. They already have numerous side dishes and feasts, a back catalogue that they haven't been able to fully consume yet. So it's better to just make the smallest, most awesome dessert, or aperitif, or salad. That can be something they remember. It can have an impact on them."

Whether Tiger Style sees its own future in those terms, though, is still undecided. Back in 2009, many of us in the press saw the provision of a fertile environment for indie developers like Tiger Style as the single best aspect of the rise of mobile games. Today, just six years later, that humble hope seems almost beyond grasp, and the dollars earned by the market's top-grossers is cold comfort. Indeed, Smith is endearingly frank about his perception of mobile's big hitters - "those tend to be, pretty much, corporate, free-to-play, revenue maximising, psychology abusing, sell out, lowest common denominator bullshit" - but it's also clear that the principles on which the studio was founded don't easily fit into any part of the market as it currently stands.

"We're going to have to go back think about whether we can release games that make money and still feel like Tiger Style games," Smith admits. "If we had the idea for Waking Mars today I don't think we would release it. Doing so in this market would basically be an act of charity on our part. We would never make the money back."