Recollections of Rez

Tetsuya Mizuguchi looks back on the creation of his seminal synesthesia shooter

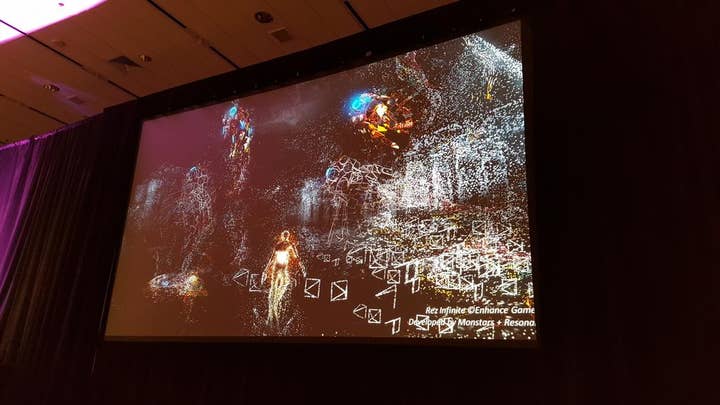

Though it was originally released on the moribund Dreamcast in late 2001, Tetsuya Mizuguchi's rhythm-driven on-rails shooter Rez made a clear impression on the industry. It was re-released on PlayStation 2, remade with HD visuals for the Xbox 360, and conceptually revisited by Mizuguchi himself with 2011's Child of Eden. That legacy looks to extend into the future, as the developer hopes to mark the game's 15th anniversary by launching Rez Infinite for the PlayStation VR in time for the headset's launch this October.

However, in a Game Developers Conference session Thursday morning, Mizuguchi was less concerned with the future of Rez than the original game's development, delivering a post-mortem for the seminal shooter.

Mizuguchi began his talk explaining his creative inspirations, citing two games as formative experiences that provided the original seeds of an idea that would become Rez. The first was 1982's top-down arcade shooter Xevious, and the second was 1989's Xenon 2: Megablast.

Mizuguchi was a high school student when he first discovered Xevious, and found that the more he played it, the more fixated he became with the idea that the game's sound effects combined to play music back to him. Though he wouldn't discover Bitmap Brothers' Xenon 2 until he was in university, that game's audio had a similarly profound impact on him.

"It really almost shocked me, and it was a realization that this game gave me a sense of a new media perspective, meaning games as an art form can exist, and the marriage of games and sound and music was something that, for me, was undiscovered at that time until I met this game," Mizuguchi said.

Those games gave him the hope that he could turn his love of both games and music into the same fulfilling career, which led him to take a job with Sega. One of his first projects for the publisher was Sega Rally, and though it was an arcade racing game, it was also clearly a multi-sensory experience, with audio and force feedback playing greatly into the feel of the experience.

That wasn't the only multi-sensory experience Mizuguchi had early on at Sega. His travel with the company opened his eyes to all manner of different experiences, both in gaming and beyond. For example, it brought him to Zurich's Street Parade, essentially a techno dance party, where he was blown away by the simple beats synchronized with the colors, light shows, and movement of people. It reminded him of the concept of synesthesia, in which people might feel they can hear colors or see sound.

The concept took hold, and Mizuguchi studied previous artists' explorations of the idea. He was particularly taken with the work of Bauhaus painter Wassily Kandinsky, who walked the streets of Moscow and "painted the sounds he saw," combining what he saw and what he heard into expressive paintings. Game developers could do the same thing in computer form, he reasoned.

That was the genesis of Rez, a marriage of game and music where players create the music as they shoot down enemies, putting themselves into a sort of trance state.

If he was going to realize that idea, Mizuguchi knew he needed to better understand the nature of music, of performance, and why music ultimately just makes people feel good. The developer took a somewhat academic approach to the problem, starting with careful observation of the phenomenon of music.

One of the development team members had shot a video outside a café in Kenya where a group of street musicians had started playing music and attracted a small crowd of happy dancing people. Mizuguchi said the team must have watched that video 100,000 times trying to figure out how such a group would get started and triggered, how it would bring people in. If Mizuguchi couldn't figure that out, he reasoned it would be impossible to tell his programmers how to replicate it in a game.

He settled on the idea of "call and response" as one solution that resonated with the team members. He likened it to the performance aspect of a DJ. Strictly speaking, a DJ doesn't need to do much more than push play on a given track. But with the exact same music, the DJ can elevate the crowd's enjoyment and engagement with dancing, gestures, clapping, and so on. To better understand the nuances of this, the Rez team performed extensive research by going clubbing or attending taiko drum festivals.

That research paid off when Mizuguchi said they finally found "the magic," a technique he called "Quantization." Because players in the game were essentially building the music and sound effects through their actions in the game, things would work well if the person had a natural rhythm to their play. But Mizuguchi wanted the game to have the same transcendent effect on people regardless of whether they could keep a beat, and quantization was a way to achieve that. Even if players played in an offbeat manner, the game would fiddle with the timing of call and response mechanisms to force things to happen in proper synch. The idea has worked so well Mizuguchi has brought it forward into his other games, including Child of Eden as well as the puzzle game Lumines.

Narratively, there were two stories to Rez. In the official story, the player was a cyberspace hacker trying to save the world by purifying and rebooting a network. In Mizuguchi's other story, the player is just a sperm on a long journey to the egg, an extended metaphor that ends with the player's birth. Every person had that experience before they were born, Mizuguchi said, so perhaps the game could have tapped into some inaccessible memories of it.

Mizuguchi also discussed the origin of the game's name, which he had originally considered to be a shortened version of "Resolve." But during a studio visit by some editors of Edge, Mizuguchi was asked if it was reference to the movie Tron, where characters in a digital world can be dispersed, or "de-rezzed." Mizuguchi liked that, because it suggested that characters were "rezzed," or brought together, much in the same way Rez was trying to bring together a multi-sensory experience.

"You can feel the sound. We can express the sound textures like percussion or guitar bass. Any type of sound we can express, you can feel."

One of the key parts of that multi-sensory experience was haptic feedback. The PlayStation 2 version of the game had controller rumble, but it wasn't enough for Mizuguchi's taste, so they introduced a Trance Vibrator peripheral for players to wear while they played. But it still wasn't enough, so now some 15 years later, with the announcement of Rez Infinite for PlayStation VR, Mizuguchi created a one-of-a-kind "synesthesia suit," a costume equipped with lights and 26 different vibrators to provide a more thorough multi-sensory experience.

"You can feel the sound," Mizuguchi said. "We can express the sound textures like percussion or guitar bass. Any type of sound we can express, you can feel."

In case he hadn't made it clear, Mizuguchi later added, "I love vibration."

With Rez, Mizuguchi wanted to create a game that payers wouldn't just play and leave behind. He wanted something they would play often simply to feel good, a new form of media experience.

"Our job is to create experiences, or recreate and redesign experiences," Mizuguchi said. "So even though I was young at that time and we may not have had all the experiences we do now, we squeezed out every ounce of energy, blood, sweat and tears to figure out how we could channel that experience through this game and make something you would want to play over and over."

Ultimately, Mizuguchi said, the creation of Rez wasn't just a difficult journey. It was a treasure.