People of the Year 2015

The individuals and the teams who made their mark on our industry over the last 12 months

Every entertainment industry relies on collaboration to achieve the very best results, and that may be more true of games than any other. The number and variety of disciplines now required to create, release and operate a game make effective teamwork more important than ever before. Individual excellence is still possible, of course, but there are occasions when great achievement cannot be attributed to a CEO or a public figurehead. When preparing the shortlist for our People of the Year of 2015, it was immediately clear that drawing a line between the individual and those around them can sometimes feel arbitrary - even unfair.

In that regard, the names that didn't quite make the cut are as illustrative as those you'll read about below. Davey Wreden is as fine an example of an individual creator as this industry has to offer, and in 2015 he followed The Stanley Parable's structural gymnastics with the intensely personal and no less brilliant The Beginner's Guide. Colossal Order managed to beat SimCity at its own game with fewer than 20 people, releasing Cities Skylines to great acclaim and record sales for its publisher, Paradox Interactive. Studio Wildcard is a larger developer, and it had a larger hit with Ark: Survival Evolved, building that success in collaboration with some 2 million players through Steam Early Access. And then there's Bungie, one of the biggest names in the games business, fulfilling the enormous potential of Destiny with The Taken King.

All would be worthy inclusions on any list of 2015's best and brightest. Here, in no particular order, are those picked by the staff at GamesIndustry.biz.

Hipster Whale, developer of Crossy Road

"Hipster Whale wanted to make a free game that people could play and love and share. In doing so, it created perhaps the year's most successful mobile title, in terms of dollars recouped for dollars invested"

For Matt Hall and Andy Sum, the year started on a high. The simple mobile game they had brainstormed between stodgy sessions at a developer conference and finished in a handful of months was doing well. To put a finer point on it, Crossy Road was doing very well indeed.

At the start of a year that was supposed to play host to an indie-pulverising cataclysm, these two Australian developers - aided by sterling artwork from their collaborator Ben Weatherall - had earned $1 million from advertising within two months. Neither Hall nor Sum expected anything close to that kind of return. "We don't want to get any bigger," Hall said when he talked to GamesIndustry.biz shortly after Crossy Road hit 40 million downloads, and yet six weeks later that $1 million in revenue had become $10 million.

Exactly what Crossy Road's lifetime earnings are at the close of 2015 is for the educated guessers out there, but the scale of its success was certainly enough to send Hipster Whale's initial desire to "open the books" on a collision course with their natural humility about that new-found wealth. Hall and Sum wanted to make a free game that people could play and love and share, where the user didn't feel that, by putting their finger on the screen, they were tacitly agreeing to a hand grasping for their wallet. No consumables, no save-me buttons, no subversions of the game's appeal in exchange for a few extra dollars. In doing so, they created perhaps the year's most successful mobile title, in terms of dollars recouped for dollars invested.

For those who still itch a little when contemplating free-to-play, and for those who had started to see mobile development as impossibly hostile to small teams, Hipster Whale and Crossy Road were invigorating outliers - an antidote to "Indiepocalypse" paranoia.

Psyonix, developer of Rocket League

"Rocket League distills so much of the appeal of video games as a form into wonderful bursts of ridiculousness"

The story of Psyonix, the Californian developer of Rocket League, is one that borders on the obsessive. Studio founder Dave Hagewood's career had revolved around putting cars in things, progressing from a mod that added various vehicles to Unreal, to adding that mod to Unreal Tournament 4 under the official auspices of Epic, and then to the awkwardly titled precursor to Rocket League: Supersonic Acrobatic Rocket-Powered Battle-Cars, which came to PS3 in 2008.

SARPBC was something of an accident, born when one of the Psyonix team added a football to what was intended to be a game about automotive combat. But it provided a template for the piercing simplicity and direct joy of Rocket League, which distills so much of the appeal of video games as a form into wonderful bursts of ridiculousness.

Projected to wide acclaim on the back of an excellent decision to publish as a free title on PlayStation Plus, Rocket League's trajectory has also benefited from savvy DLC choices - like adding Back to the Future's Delorian and free content themed around Valve's Portal. And it's gaining traction as a serious esport, too, with top level players exhibiting the sort of astonishing finesse most of us wouldn't think possible. The fact that the spectrum of play is so broad, that something so absurd has such wide appeal, that it pulls off the impression of being an idea birthed at closing time when it's actually an intricate refinement of myriad design decisions; these qualities make Rocket League special.

Some of the staff here at GamesIndustry.biz are terrible at Rocket League, clattering into walls, players and occasionally the ball with total ineptitude - over excited photons in a house of mirrors. But if you don't like football and you don't like driving games, you can still love Rocket League.

Satoru Iwata, former president and CEO of Nintendo

"That may be what we all remember best about the man - he wasn't one of those stuffy executives who looks down his nose at you. Iwata was genuine, polite and endearing"

In July of this year, the venerable head of Nintendo Satoru Iwata died at 56 years of age. While it was public knowledge that he'd been battling illness, his death came as a shock to many in this industry, and we'd be remiss not to include Iwata-san in our list of the most important figures in the business.

With Iwata gone, an era ended at Nintendo. After taking over as president (the first not from the Yamauchi family) in 2002, he pushed Nintendo in new and exciting directions, overseeing the launches of the DS handheld and the Wii console. These platforms were widely ridiculed at first sight but went on to become enormously successful, propelling Nintendo's net worth to heights never before seen in its long history. After struggling with the Gamecube Nintendo had found its mojo again, largely thanks to Iwata's leadership and desire for Nintendo to stand on its own with unique, innovative products.

For better or worse, Iwata was truly the face of Nintendo, and he put himself out there with Iwata Asks Q&A sessions and by introducing the Nintendo Direct videos. There was better and more direct communication with fans and shareholders than ever before. But as the head of a major Japanese corporation, Iwata was also beholden to those shareholders who became increasingly impatient as Nintendo's profits evaporated with the Wii U and 3DS systems that simply couldn't match the scale of their predecessors' success.

Through it all, and even with immense pressure in his final years as some investors rudely questioned how his illness affected his performance, Iwata was ever the gentleman. And that may be what we all remember best about the man - he wasn't one of those stuffy executives who looks down his nose at you. Iwata was genuine, polite and endearing.

Nintendo has no choice to push on now without Iwata-san. The challenge facing Nintendo and his successor Tatsumi Kimishima is enormous. Following the Wii U, can Nintendo reclaim a healthy share of the console market with the NX? Will the company be able to succeed in the world of mobile gaming? Iwata's impact may yet still be felt in the years to come, as his final input into these business decisions undoubtedly will play an important role in Nintendo's unfolding strategy.

CD Projekt, creator of The Witcher franchise

"The passion that has powered the company forward since its foundation in 1994 reached a perfect crescendo, manifesting as one of the best games of the year, developed and published on its own terms"

A few months ago, a rumour surfaced that Electronic Arts was poised to buy CD Projekt Red. The story was quickly dismissed by CEO Marcin Iwiński, with the same good humour that categorises so many of his interactions with the press and the public. As with even the flimsiest of fabrications, though, the initial reaction can be just as revealing as the official clarification.

It is very much to CD Projekt's credit that people were so willing to believe that EA was knocking on the door of its Warsaw headquarters. The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, the studio's most ambitious game by a long chalk, had sold 6 million copies in little more than six weeks, rivalling the milestone that its two predecessors had needed six years to reach. The company's six-month revenue increased by almost 600 per cent, its net profit rocketed from just over $1 million to more than $60 million, and all of it achieved to a chorus of near unanimous critical adulation. At that moment in time, a great many in the industry were looking on CD Projekt with a mix of admiration and envy, so why not EA?

Frankly, it would have been easy to justify CD Projekt's inclusion on this list in 2011, when The Witcher 2 so emphatically surpassed its agreeably scrappy predecessor. Or for its commitment to shining a light on classic games through GOG.com. Or its consistent and uncompromising stance against DRM even in the face of rampant piracy. But the truth is that 2015 is the right year for venerate CD Projekt, the year when the passion that has powered the company forward since its foundation in 1994 reached a perfect crescendo, manifesting in one of the best games of the year, developed and published on its own terms.

When GamesIndustry.biz met with Marcin Iwiński in Poland last year, he encouraged creators to take more responsibility when telling the world about their games. "They are the vision holders, they are the passion holders," he said. "Only the developer can change their reality." In 2015, CD Projekt tested the very limits of that belief, and in doing so changed its reality for years to come. That kind of achievement can't be bought, at any price.

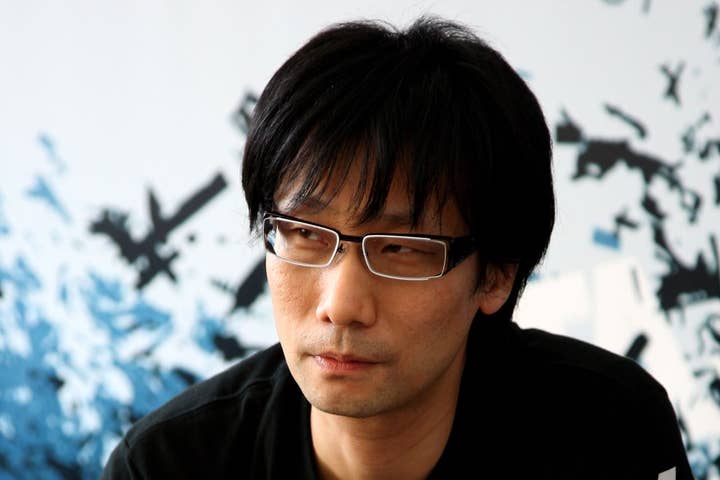

Hideo Kojima, legendary game designer

"The Kojima-Konami split raises questions about the true value of a rockstar developer. How much of the Metal Gear brand's value is inextricably tied to Kojima's particular vision?"

We knew going into 2015 that it would be a big year for Hideo Kojima, what with the expected launch of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. After all, the director had said The Phantom Pain would mark the end of his involvement with the series. Granted, Kojima has said that about pretty much ever Metal Gear game over the last 15 years, but as with any good boy-who-cried-wolf story, the last such proclamation appears to have come true.

In March, just a couple of weeks after Konami announced a final release date for The Phantom Pain, rumors of a rift between Kojima and the publisher's management surfaced. Konami pulled Kojima's name off the marketing and box art for not just the Phantom Pain, but also digitally distributed versions of older Metal Gear titles. It also eliminated the Kojima Productions website and Twitter account, and the high-profile developer was largely absent from promotional activities from then on.

The Phantom Pain launched September 1 and was a resounding critical and commercial success, but those holding out hope that it could mend the relationship between Kojima and Konami were quickly set straight. In October, The New Yorker reported that Kojima had cut ties with Konami, with his non-compete clause ending this month. Curiously, Konami responded to the report by simply saying Kojima was on vacation. And in an act that can only be construed as pettiness unbefitting of a major publisher, Konami used its contractual leverage over Kojima to bar the developer from personally accepting year-end awards for Metal Gear Solid V.

Beyond adding a dose of drama to the game's release, the Kojima-Konami split raises interesting questions about the true value of a rockstar developer. How much of the Metal Gear brand's value is inextricably tied to Kojima's particular vision? Konami has pledged to press onward with the Metal Gear franchise, but how many of the same creators will be involved behind the scenes? In each game he directed, Kojima put a new spin on the Metal Gear formula, but will the fanbase be accepting of new takes on the series when he isn't the one at the helm? Is Konami better off trading in Kojima's vision and celebrity for an unknown director with fresh ideas but without the sway to go over time and over budget? Can Kojima succeed financially without the Metal Gear brand or a publisher the size of Konami to bankroll his vision?

Jessica Curry, former studio head at The Chinese Room

"A letter of resignation isn't Jessica Curry's legacy. That can be found in the brilliant work that went before it, and the music that's still to come"

Jessica Curry is a BAFTA-nominated composer, whose game scores have topped the iTunes soundtrack charts. She's worked with The Royal Opera House, the Welsh National Opera, the Arts Council for England, PRSF, Prix Ars Electronica and The Royal Society of Arts. She's the co-founder and studio head of The Chinese Room, an acclaimed indie studio producing unique, fascinating games. She's currently collaborating with poet laureate Carol Anne Duffy on a major project.

Her talent has been recognised by media, institutions and players around the world, but still, the reason you've probably heard of her is that, this year, Curry wrote an extended, heartfelt and intensely sad open letter describing why she was effectively stepping down from The Chinese Room and taking step back from a career in which she'd achieved so much.

Partly it was illness. A long term degenerative disease is, in the horribly insidious nature of these conditions, gradually worsening, making a profession so draining a virtual impossibility. But it wasn't just her illness. In her letter, which anyone working in games should take the time to read and to digest, she spoke eloquently about the toll that working with a publisher has taken upon her wellbeing, the exhausting nature of attempting to marry raw creativity to a capital endeavour. Thirdly, and perhaps most poignantly, there's the nature of her treatment as a woman in the games industry, and the constant attrition of the fight for recognition. Again, her words should be read first-hand rather than summarised.

Jessica Curry isn't a person of the year because she felt so aggrieved by the treatment she'd received at the hands of the industry she excelled in that she had to quit. Her strength in adversity is admirable, of course, but a letter of resignation isn't her legacy. That can be found in the brilliant work that went before it, and the music that's still to come.