AAA should invest in indies - Ori dev

Thomas Mahler talks about his studio's reputation, distributed development, and the project he'd love to sign to a publisher

Moon Studios' Ori and the Blind Forest has drawn plenty of comparisons to Studio Ghibli, with a quality of animation and bitter-sweet story beats reminiscent of the studio behind Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro. The comparisons are further cemented by Ori's commercial and critical success, making its money back in its first week on sale and posting an 89 Metacritic average on the way. A reputation as the Studio Ghibli of Games could be in the cards for Moon, but it remains to be seen if the company would actually pursue it.

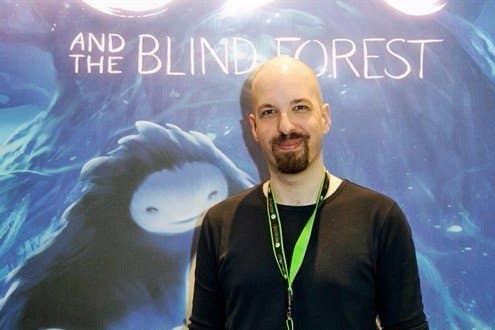

As the studio weighs its next move, CEO Thomas Mahler spoke with GamesIndustry.biz to discuss what brought it to this point and where it goes from here.

"I don't see us just making platformers or [just] making Ori 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6."

"At Moon Studios, we want to be that game company you want to support," Mahler said. "Because really, we're just crazy people that work extremely hard on hopefully the best games we can give people. That's always the strategy. ... We set out to create the best games in the world, because studios with that kind of idea behind them--like Blizzard and Nintendo before them--they always get their trust from people, and I think that's just a winning formula. In some ways, I have to sacrifice a lot to make that work and for Moon Studios to be that kind of studio. I think that's just what we want to do. I don't see us just making platformers or [just] making Ori 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6."

The idea that Moon would have aspirations of variety beyond churning out sequels in a single franchise is not surprising. While Ori is its first released game, Moon did have an earlier project it publicly unveiled called Warsoup. A first-person shooter with the structure of a real-time strategy game, Warsoup was an idea spawned from Mahler's experience at his previous job with the cinematics team at Blizzard. After spending his lunch breaks learning the finer points of Starcraft II from his co-workers, Mahler wanted to adapt some of the same gameplay dynamics to the first-person shooter genre. Instead of casting the player as an all-powerful eye-in-the-sky issuing commands to build refineries, farm minerals, and research weapon upgrades, Warsoup would put players on the ground, making them juggle many of the same tasks while also using their fancy weapons (which must be researched anew each round) against one another. Early clips of the game can still be found on YouTube.

Emboldened by the then-recent trend of indie games like Braid and Castle Crashers hitting it big on Xbox Live Arcade, Mahler worked on the prototype for Warsoup in his free time at Blizzard. He'd leave the office at 8 p.m., go home and crank away on Warsoup until 3 a.m. He put together a team of developers that would become Moon and began pitching projects to publishers. Microsoft was one of the companies he pitched, but they weren't so taken with Warsoup. Instead, it was a secondary project that grabbed their interest, a platformer called Sein that would eventually become Ori and the Blind Forest.

"I think the reason Microsoft was more interested in Sein back then was because we were a really small studio and they didn't really think that it made sense for us at that point to try to compete with all the online multiplayer first-person shooters out there," Mahler said. "And I think they were probably smart about that."

It wouldn't take long for evidence of that to start surfacing. Mahler said within a couple weeks of development, the team "already had a prototype up that felt as good or better than Super Meat Boy," adding that Super Meat Boy had been his gold standard of platforming control excellence, nailing the feel of the controls in a way that hadn't been done since Super Mario Bros. 3.

"As a sculptor, the first thing you learn is that you block things out. You start with something in a very rough shape, and only when the rough shape really works do you start adding some details."

The rest of the game would not come together as quickly. Moon Studios spent four years working on Ori, much of it on ideas that didn't actually make it into the final game. For example, the team had prototyped one area that took place within the belly of a whale, with walls that expanded and shrank as the animal inhaled and exhaled. Mahler compared the process to two other pursuits: writing and sculpture. For the former, he pointed out that the author of a 600-page best-seller might have to write 1,000 pages of content before they started to distill it down to the most effective story. For the latter, he reflected on his art school education in traditional sculpture.

"It completely changed my whole way of looking at everything and how I work on things," Mahler said of the art school experience. "As a sculptor, the first thing you learn is that you block things out. You start with something in a very rough shape, and only when the rough shape really works do you start adding some details. And then you look at it again, rough out some other stuff, start adding details here. And more and more, the stone is showing you what it wants to be. With everything else I do--if I write a story, draw something, design a level--I approach it now in the same way and it almost happens subconsciously. You just work that way because it's the most natural way of doing things."

As of yet, the stone that is Moon Studios hasn't quite shown what it wants to be, either. For Ori, Moon had to give up the rights to the intellectual property in order to get the game's development funded. And even though the studio undoubtedly has more leverage at this point to insist on owning the IP of anything it produces, Mahler said that decision depends in large part on the project.

"I have a couple of things right now where my mindset is, 'I do not want to give this to a publisher. I want to run with this myself and self-finance it because I think it makes the most sense for this game because it's a small game,'" Mahler said. "There's another thing that I would love for a publisher to jump on it, but they would never do it because there hasn't been a thing like that yet."

"It's kind of embarrassing if you look at the video games industry and how they've handled World War II as a topic."

That thing is Project Memoir, one of five prototypes currently in the works at Moon, and actually dates back to Mahler's time at Blizzard. Mahler described it as an interactive documentary about Rudolf Vrba, a Slovakian Jew who escaped Auschwitz in 1944 and informed the world of the horrors perpetrated by the Nazis. He didn't reveal much about the proposed gameplay behind Project Memoir, but did cite Telltale's The Walking Dead games as giving developers some interesting cues on ways to pull people into a game world.

"Putting people into the roles of another person and having to make decisions that have weight, that's something you can't do in any other medium," Mahler said. "You can't do it with a book. You can't do it in film. You can't really do it with music. You can't do it with anything that isn't interactive. But games are interactive."

"It's kind of embarrassing if you look at the video games industry and how they've handled World War II as a topic," Mahler added. "If you really want to see how far behind games are in terms of storytelling, you just have to look at that. There are so many World War II games coming out, and every single one misses the boat on the really interesting things you can tell here, super-fascinating things in terms of human psychology, the history of mankind, and so on. And every single game was just about, well, shoot some Nazis. It's just stupid."

Mahler wants Project Memoir to be an entertainment product that also serves as a thought-provoking piece of art, but in the industry as it currently stands, there's little room for that.

"I would have a very hard time going to a corporation like Microsoft, Activision or EA and saying, 'Hey do you want to finance my game that is extremely controversial and is a story-based game, an interactive documentary thing that hasn't been done before and there's no way of knowing if this will be successful or not. Do you want to finance it?' That's something I'd like to see. There's no way right now in this industry to make something like a Schindler's List for games.

"It's this risk I'm taking where right now I'm investing quite a lot of money into this and have two developers working on it, but I don't know if it'll ever get to that level of being able to release this and having it be a great thing I want to put my name on," Mahler added. "It's just a very small project, just a prototype right now. But I also already see that if we did this full-time and really put our voice behind this, it could be an incredible thing for the entire industry."

"[T]here are a lot of smart people in this industry and it doesn't make a lot of sense to always risk everything and play this high-chance poker every single time."

Like games, Mahler noted that the movie industry is hit-driven, and often dominated by light entertainment fare, superhero movies or The Fast and the Furious franchise, for example. Unlike most game publishers, however, movie companies also tend to release smaller prestige pictures, films with smaller budgets that seek to do more than keep their audience busy for a couple hours on a Friday night. He would love to see the big publishers of the world cut back on their AAA slates and use that money to finance some smaller, more ambitious bets.

"Maybe one of those games becomes the next Minecraft," Mahler said. "Nobody knows what that is, but there are a lot of smart people in this industry and it doesn't make a lot of sense to always risk everything and play this high-chance poker every single time. It doesn't make business sense to me why you don't take the $50 million or $60 million that one AAA game costs you and distribute that between 10 titles or 20 titles that you could finance that way, and maybe you have one Markus Persson in there who's going to make that next big hit. That's a model I'd like to see. Yes, there are AAA titles, and they're important. They're great, they make a lot of money. But then also you can create these small titles that could make a huge amount of money for you, a huge ROI for you, but at the same time it costs a lot less and you don't take that much risk on them. It just makes more sense to me. I don't understand why Activision isn't doing that, why Electronic Arts isn't doing that, why Nintendo is barely doing that. It just doesn't make sense to me."

That's not the only part of the current status quo Mahler would love to see changed. In fact, Moon Studios was founded on the idea that "the way things are" needed changing.

"I saw how all the studios worked, and there was a lot of good stuff I copied exactly, saying 'Yeah, we should do that at Moon.' But there was also stuff where I was thinking, 'That is inefficient and stupid,'" Mahler said.

Take the traditional developer workplace, for example. Moon was set up from the beginning to be a distributed development house. Mahler is based in Austria, but his team spans the globe. Given how comparatively rare the practice was in 2011, Mahler had expected it to be one of the biggest challenges for the fledgling studio to overcome. But with the help of tools like SVN, Hansoft, and Skype, he said the anticipated difficulties never really materialized.

"I just don't see the value in sitting down together in an office," Mahler said. "What is the one point you can do when you all sit in an office that you can't do with the tools we have, with the pipeline we have right now?"

"I just don't see the value in sitting down together in an office. What is the one point you can do when you all sit in an office that you can't do with the tools we have, with the pipeline we have right now?"

The benefit of distributed development was more compelling to Mahler. Now when he discovers talent that would be a perfect fit for the studio, it doesn't matter where they are, or what obligations might be keeping them from packing up and moving across the world to join a new studio.

"If I would have had to just use talent I could find in Austria, there's no way we could have done Ori," Mahler said. "There's just no way. We would not have found all these people, all that talent just packed together into one location. That's just not possible."

The downside of distributed development means the team doesn't get to share "water cooler moments" the way they might in a traditional office, but Mahler sees it as a more-than-acceptable trade-off. As for substitute team-building tactics, Moon took the development team to Disneyland Paris for a vacation and for many to meet face-to-face for the first time.

Of course, this approach likely wouldn't work as well with a AAA development team, and Mahler is mindful about managing the size of the studio.

"The big fear that every small studio should have is to scale up too quickly and without proper planning," Mahler said. "I always respected the hell out of John Carmack for being very smart. Even when they were very successful at id with Doom and Quake and so on, they kept the studio fairly small. And I think that's a very good thing."

Right now, Moon has a core team of under 10 people. At its peak, it had scaled up to about 20 people with contractors. It's a far cry from Mahler's time on the Blizzard cinematics team.

"You learn this as an artist very quickly that ego is just really shit for you."

"When I was there, there were 150 people just in that department," Mahler said. "At that size, there's no way you know everybody by their names. Even if you're the director of the game and you have a concrete vision in your head, because there are so many people working on the game and contributing to it, there's no way you're going to get exactly that [vision] because there are so many hands in it. At Moon, we wanted to take a completely different approach. We've got to have a way smaller studio. We're going to work in this family atmosphere of 8-9 people, and that's our core team."

When the team is that small, Mahler said it's possible for everybody to have a voice. He wants Moon to be a studio where anybody can suggest ways to improve the game and have their arguments considered, from the designers to the playtesters. Clearly, he's not a fan of the "auteur" model of game development.

"You learn this as an artist very quickly that ego is just really shit for you," Mahler said. "If you put your ego out there and are like, 'No, I'm the CEO of the studio. I always have the best ideas,' that's just fucking bullshit and it ruins a company really, really quickly. Because everyone has to have the feeling of having a lot of responsibility on the team, making big decisions, and being really valuable. If you give people that chance to prove themselves and have something to say, if you let them have that influence, then you get their best work... What actually makes me wonder is how easily great artists and great programmers at all these studios are willing to accept that there's this one person and we all just have to do what he's saying, even though he makes decisions that also affect my livelihood and the product I'm making and the product I'm investing years into."