"PC is decimating console, just through price" - Romero

Doom creator talks free-to-play, VR and more as his old Apple II is added to The Strong museum

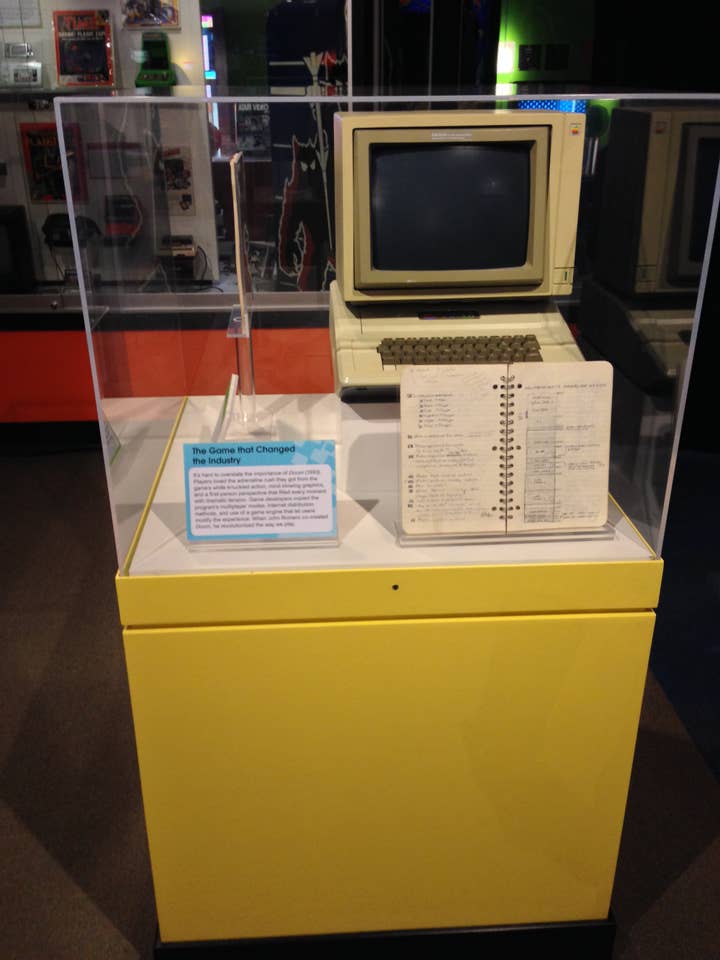

This week in Rochester, New York, The Strong museum's eGameRevolution exhibit held a special ceremony to add John Romero's old Apple II Plus computer to its growing collection of historically important video game artifacts. Romero also donated one of his original notebooks which has game maps and tons of lines of code for his games, including Dangerous Dave (1988), which he's close to re-releasing on iOS and Android. Importantly for Romero, his Apple II was installed right next to the display for Bill Budge's Apple computer.

Romero, who's now creative director for the Games and Playable Media Masters degree program at UC Santa Cruz, told GamesIndustry.biz that Bill Budge was "a huge, huge inspiration" in his career, and he's "super honored to be part of this amazing museum."

Romero described how computers back in the '80s didn't enable multi-tasking, so he got in the habit of writing down notes for everything as he programmed since there was no separate notepad editor that could be open at the same time. "I had to write my notes down because I couldn't shift into a text editor... Nowadays I keep journals on everything I do even on an hourly basis for any of the stuff I'm programming," he said.

Younger game developers today may not realize it, but the Apple II was a real boon for aspiring game makers like Romero in the '80s. "The Apple II was an amazing computer to learn on. When you turned it on, immediately you could start programming. The language is built in ROM. Nowadays you can't really do that. You have to find an SDK and get an editor and run a simulator and all this stuff to actually do interactive programming. On the Apple II, you just turn it on and can program immediately and you see the results of your code as soon as you type 'run'. That was really important in being able to learn very quickly how to do stuff," he explained.

While Romero definitely sees parallels between the old PC garage development days and the rise of the indie scene in the last few years, there were many more barriers for developers to contend with back then - most notably publishers who acted as gatekeepers.

"It's so much easier now. The whole game industry was created by indies. The publishing companies like Sierra, Broderbund, etc... the games that they published were sent to them by indie developers. The big publishers of the early '80s were indie publishers. And nowadays because there are so many SDKs to create with and people can put their apps out there on a store without any real publisher intervention, everybody can publish. There's no stopping anybody. Minecraft was put up on a webpage - you can publish on the web, you can publish through app stores, there's no one stopping you," Romero said.

He added that the big challenge for today's crop of developers is to get better at marketing. "Now everybody just needs to get wise about how to advertise and market; but really it's so much easier now. I can't even imagine making a game in 1983 and somehow getting it in a store. That's hard to do because of all these barriers between me and that store. Other people have to make decisions on it. If anybody wants to make a game nowadays, they can make their own decisions," he said.

"With PC you have free-to-play and Steam games for five bucks. The PC is decimating console, just through price. Free-to-play has killed a hundred AAA studios"

Similar to how Romero and other developers altered the games business with quality shareware games, the Doom designer believes that free-to-play is similarly shaking up the industry for good.

"With PC you have free-to-play and Steam games for five bucks. The PC is decimating console, just through price. Free-to-play has killed a hundred AAA studios," he remarked.

"It's a different form of monetization than Doom or Wolfenstein or Quake where that's free-to-play [as shareware]. Our entire first episode was free - give us no money, play the whole thing. If you like it and want to play more, then you finally pay us. To me that felt like the ultimate fair [model]. I'm not nickel-and-diming you. I didn't cripple the game in any design way. That was a really fair way to market a game," Romero continued. "When we put these games out on shareware, that changed the whole industry. Before shareware there were no CD-ROMs, there were no demos at all. If you wanted to buy Ultima, Secret of Monkey Island, any of those games, you had to look really hard at that box and decide to spend 50 bucks to get it."

For the free-to-play crowd, Romero believes that the popularity of games that have done it right (like World of Tanks) will ultimately raise the bar for the model, and consumers will easily spot developers who make free-to-play titles the dirty way.

"Everybody is getting better at free-to-play design, the freemium design, and it's going to lose its stigma at some point. People will settle into [the mindset] that there is a really fair way of doing it, and the other way is the dirty way. Hopefully that other way is easily noticeable by people and the quality design of freemium rises and becomes a standard. That's what everybody is working hard on. People are spending a lot of time trying to design this the right way. They want people to want to give them money, not have to. If you have to give money, you're doing it wrong... For game designers, that's the holy grail," Romero said.

Romero sees the games platform landscape now being dominated by PC and mobile. Consoles, he said, are not only being hurt by the free-to-play trend, but also by their inherently closed nature.

"The problem with console is that it takes a long time for a full cycle. With PCs, it's a continually evolving platform, and one that supports backward compatibility, and you can use a controller if you want; if I want to play a game that's [made] in DOS from the '80s I can, it's not a problem. You can't do that on a console. Consoles aren't good at playing everything. With PCs if you want a faster system you can just plug in some new video cards, put faster memory in it, and you'll always have the best machine that blows away PS4 or Xbox One," Romero commented.

And as much as Romero loves bleeding edge technology, he remains skeptical when it comes to virtual reality. The designer believes that VR headsets still require too much effort for many players.

"Before using Oculus, I heard lots of vets in the industry saying this is not like anything we've seen before. This is not the crap we saw back in the late '80s. I was excited to check it out and I was just blown away by just how amazing it was to just be in an environment and moving my head was just like mouse-look. I thought that was really great but when I kind of step back and look at it, I just don't see a real good future for the way VR is right now. It encloses you and keeps you in one spot - even the Kinect and Move are devices I wouldn't play because they just tire you out," he remarked.

"Really the best optimal design for games is minimal input for maximum output - that's the way that games work best. When you watch people playing with a mouse and keyboard, you see them barely moving their fingers and hands but on screen you see crazy movement and all kinds of stuff. Everyone always goes for the path of least resistance and that kind of input is it. Until it can fix the path of least resistance, I can't see how VR is going to be something that's popular."

Romero added that VR makers are going to have a tough challenge in building up an installed base for developers as well. "The only way to hope that it'll be popular is to include it with every computer sold. And being on PC there's no way - you'd have to get in with Apple or somebody that can actually have it built in because everyone else is like a free agent. I can't see VR being the next big thing for games because we've had many of these peripherals that were non-standard come through - the early '90s until now there's always a weird peripheral to do something."

Romero also agrees with Nintendo and others who have noted how VR is actually isolating, whereas games now are actually more social. "VR is going away from the way games are being developed and pushed as they go back into multiplayer and social stuff. VR is kind of a step back, it's a fad. Maybe in the future there will be a better VR that gets you out of isolation mode," he said.

Ultimately, he said, VR could serve a cool niche for some of the hardcore gamers with good PC rigs. "The fact that it encloses you or makes you do something different than what you're used to naturally doing also makes it a hard thing to adopt. Even though I'm excited about VR and how cool games look, I can't see it becoming the way people always play games. I can see it being like Steel Battalion - if I'm going to play that game I'm only playing it with that controller... I can't see every game being able to translate that experience to VR, because VR right now works best if you're just sitting. If you're inside of a cockpit, that's cool, but if you're supposed to be running around a world and you can't physically run but you can look around, it's a weird disconnect and it doesn't feel right. I think we're still waiting for the holodeck."