The Astronauts: 'It's just a game' design

Adrian Chmielarz on moving beyond his intuition with The Vanishing of Ethan Carter

Adrian Chmielarz is a great believer in freedom. His experiences making Bulletstorm with People Can Fly clearly illustrated the weaknesses inherent in the game-on-a-disc-for-$60 model on which the AAA industry had come to rely. The practical demands of distribution, marketing and retail were so suffocating that they had become as influential on the content of games as the whims of the people making them. For Chmielarz, the commercial failure of Bulletstorm was a symptom of that system being brought to its knees. It was difficult, certainly, but it was necessary to usher in a new and vibrant era of creativity.

And it all comes down to freedom. The freedom to tell any story at any length, to find the right audience and set the right price. Chmielarz has no illusions that achieving success will be any easier for The Astronauts, his new studio, than it was for People Can Fly, but there is an opportunity for independent developers to supplement the limited palette of AAA gaming, and to do so on their own terms.

"What we had in those games [Painkiller and Bulletstorm] was, in part at least, a response to what was happening in the shooter genre and the shooter market at that time. We felt that it lacked imagination, it lacked spark, it was becoming boring. And that's incredible," Chmielarz says.

"These are games where you press the trigger and bullets come out. It's instant gratification and, to be honest, that core combat loop is one of the easiest things to make. So, in theory, we should see a lot of really imaginative shooters out there, but that wasn't the case. It was puzzling to us, so - I know it's a cliched saying - we made the games that we wanted to play."

If that felt like original thinking at the time, Chmielarz became a harsher critic of his work after he left People Can Fly. Certainly, when placed next to many of their peers Painkiller and Bulletstorm still seem refreshing, and Chmielarz is clearly proud of what they accomplished, but he now holds himself to a different set of standards. After a lifetime of playing games, Chmielarz says, it's perfectly possible for a designer to get results by intuition alone, drawing from the visceral memory of play rather than any real understanding of how to push forward and break new ground.

"I feel like the more I know the less I know. I'm still learning"

"I was happy that Painkiller was fun and Bulletstorm was fun, but I didn't really have any theory behind what worked and what didn't. It was like, 'I feel like I can do more,' but I didn't have enough knowledge about what needs to change to achieve progress in games as storytelling devices. I started to realise how many things in design are basically what designers do without deep, deep understanding of how it truly affects the player."

When a developer talks about the medium in this way it's easy to dismiss as bravado or conceit, but Chmielarz obviously doesn't see himself as separate from or superior to others in his craft. Quite the opposite, in fact; Chmielarz sees himself as part of a community, the conversation littered with references to the thoughts and theories of his fellow developers, some of whom have had a profound influence on the way he approaches game design. Chmielarz now wants to make games that transcend twitchy gameplay loops and attain something more resonant and profound. He freely admits that he doesn't yet have the answers, but that's the wellspring of his enthusiasm - nobody knows, but little by little they're figuring it out

"I feel like the more I know the less I know. I'm still learning," he says. "But I wish that more designers would join us all in this because... Let me just give you an example: less than a year ago I was talking with a couple of AAA designers, and I mentioned the idea of 'ludonarrative dissonance.' Now, I use that term as an obvious thing - it's obviously a problem facing game designers - but they told me that they didn't really care. 'Nah, it's just a game.'

"My jaw dropped. It's a very simple concept, and if you question that then we have a serious problem. But that's the case, and when I play games I always see this kind of thinking. In a way, it can be described as: 'It's just a game' design."

"I was happy that Painkiller was fun and Bulletstorm was fun, but I didn't really have any theory behind what worked and what didn't"

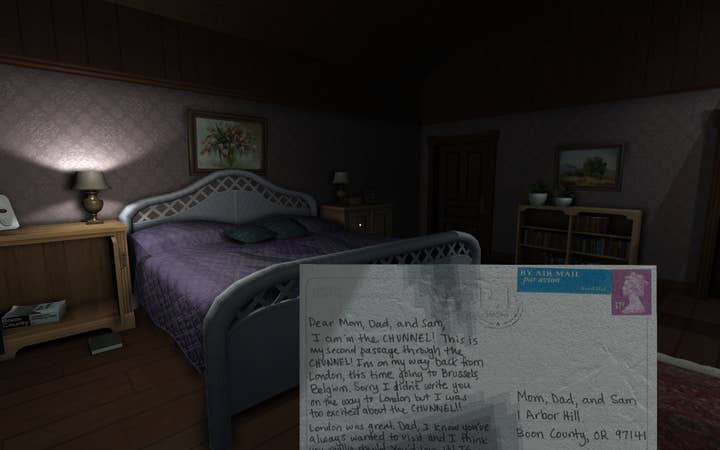

Chmielarz offers the widely lauded Gone Home as a counterexample to this tendency: In that game, The Fullbright Company found a synthesis between the game's premise and the player's actions that felt coherent and complete. At a fundamental level it employed the same basic set of mechanics used to ransack cottages in Skyrim, but by setting the game in a unique time and place, and by limiting the possible interactions with care and consideration, it created a more powerful emotional experience than most studios have managed with ten times the resources. It was a two hour game about exploring a house in humdrum Nineties suburbia, and yet it was one of the most remarkable creative feats of last year. Fortunately, Chmielarz says, Gone Home is just one of many.

"These new games are looking at the language of what we have so far, and seeing game design from a different angle. It's beautiful in a way. On the one hand you have these entertaining linear stories, which should not work as a game but they do, like To The Moon. On the other hand you have what is basically an interactive movie, like Telltale's The Walking Dead. And then on another hand you have what Quantic Dream is doing, which is their own thing. And then you have Frictional, who with SOMA is going down a completely new route. They are all using the established language of video games, but in a very fresh way. At The Astronauts we're just looking left and right, trying to figure out the formula.

"But," he smiles, "we might not need a formula at all."

I point out that, on paper and in practice, Gone Home doesn't seem to care about the one quality for which almost every game seems to strive, and on which the majority of games are sold: Fun. The same would appear to be true of The Astronauts first project, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, a kind of neo-adventure game in which the player controls a detective with second-sight attempting to locate a kidnapped child. There will be violence, Chmielarz says, but not the flippant avalanche of mayhem found in a game like Bulletstorm; Ethan Carter's violence will be used sparingly, and it will be all the more disturbing for it.

"Whatever feeling is involved, as long as it's not boring then we're doing our jobs"

Sure enough, the Ethan Carter footage Chmielarz shows at Digital Dragons features careful exploration, quiet observation, at least one horrifically mutilated corpse, but precious little that could safely be described as 'fun'. Chmielarz admits that 'fun' isn't what The Astronauts' team is aiming for, but, even in the refined air of 2014, it's still difficult to approach the marketing for any game without resorting to that sort of language.

"Actually, the perfect word to describe it comes from a blog post by Chris Pruett of Robot Invader: 'Omoshiroi', which is apparently a Japanese word that means 'interesting' or 'fun'. But space travel is interesting and it can't necessarily be called fun, so what exactly is the meaning of that word? Chris had a Eureka moment where he realised that 'Omoshiroi' really means 'not boring'. That's how I look at it now.

"Whether it makes you laugh or cry or whatever feeling is involved, as long as it's not boring then we're doing our jobs."

To read the first part of our conversation with Adrian Chmielarz, follow the link.