Indies: Market early and often or "sink into obscurity"

Antichamber dev Alexander Bruce says exposure "is becoming more and more the dominant problem" for indies to solve.

There are a few different ways to look at the explosive growth in the independent gaming scene. But where one indie developer may look at the influx of talent and attention to the market as a rising tide that will lift all ships, another may see new challenges that must be overcome.

Antichamber creator Alexander Bruce is preparing to give a featured presentation this Sunday at the Gamercamp Festival in Toronto, in which he will discuss the factors that combined to make his game a breakthrough success. Speaking with GamesIndustry International, Bruce stressed the increasingly difficult task independent developers are facing in simply getting attention for their work, saying exposure "is becoming more and more the dominant problem that people are having to solve."

Just a few years ago, developers didn't need to worry so much about their relationship with the end users. It was enough for them to have good agreements with publishers or distributors, because those were the people handling the players in most cases. These days, it's all about getting the attention of the end users instead of just a platform holder, Bruce said. Even being featured in a coveted place like the Steam Daily Deals doesn't mean as much as it used to. It's helpful, but Bruce said it only serves as a multiplier on the awareness developers had already generated for their games. And one problem a lot of developers don't seem to get just yet is that any number multiplied by zero still equals zero.

"There are people who are very good at playing to this system," Bruce said, "and if you don't do the same work to compete with them, you're going to sink into obscurity and not be known...You're the one who has to prove to other people why they should care about your game."

Bruce said marketing was a skill, just like programming or designing games, and one that developers should start honing much earlier in the process than they currently do.

"Even though I've got 250,000 sales in six months, to get that, the game needed to be seen by tens of millions of people."

Alexander Bruce

"Think about the first time you programmed a game," Bruce said. "Chances are, the first thing you programmed was not very good. If you leave your marketing effort until the very end, you're going to release your marketing materials and chances are they're not going to be very good."

Bruce pointed to Super Meat Boy and Fez as two games that benefitted from that approach. The developers began talking about those games well in advance of launch, and that gave them time to grow awareness, shape their messages, and figure out how best to garner the attention they needed to succeed. Bruce said Antichamber was the same way; it took him nearly a year and a half of trying to get attention for the title before the buzz finally started to snowball.

That protracted awareness campaign is crucial, Bruce explained, as people rarely make a purchase decision about a game the first time they hear about it. It's typically only by seeing a game come up on their favorite websites or Twitter feeds repeatedly that people finally make the effort to find out more about the title and consider buying it.

"When you look at things like Steam Greenlight and people complaining about needing 80,000 votes to even get onto Steam, it's like, getting 80,000 people to click a button that says yes first of all means you need to have an exponentially larger number of people get to your page in the first place," Bruce said. "And clicking yes takes a whole lot less energy and thought than the next step, which is actually taking out a wallet and paying for things. So even though I've got 250,000 sales in six months, to get that, the game needed to be seen by tens of millions of people. And that's something people don't really understand or take seriously, that such a small percentage of people who saw or heard about the game wound up buying it at the end of the day."

"If you happen to have a couple hundred dollars, I'd say that's your biggest problem. It's not that you need to run a Kickstarter; it's that you need to get more capital under your belt to begin with."

Alexander Bruce

Another thing Bruce said is frequently lost on independent developers is that they don't have to break the bank to stand out. Despite the array of funding options available--from Kickstarter to government grants to publishers--Bruce said it's preferable to avoid taking any of them, calling himself "a very strong advocate of working within your resources."

"If you happen to have a couple hundred dollars, I'd say that's your biggest problem," Bruce said. "It's not that you need to run a Kickstarter; it's that you need to get more capital under your belt to begin with... If you're saying we need $10,000 in order to be able to make this game, I would be asking why you're making this game that needs money you don't have initially."

That focus on working within one's resources extends to ability as well as finances. Bruce said he used to get asked what he would make if he'd been given $1 million.

"My answer was always, 'Probably make something terrible,'" Bruce said. "Because all of the best decisions that were made in Antichamber were made because I didn't have resources."

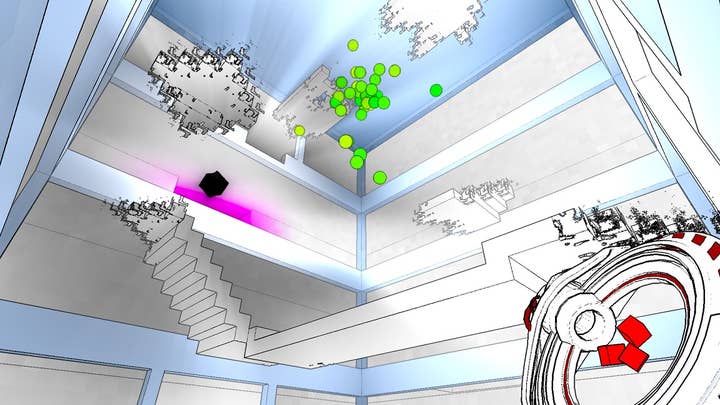

Bruce didn't have money to hire more people, and he didn't have the skill set to accomplish whatever he could think of, so he was forced to make do with what he had at hand. He arrived at the game's stark and stylistic art style after looking at the other games in Epic's Make Something Unreal contest, and knew he couldn't compete with what some of the bigger teams were putting out.

"My answer wasn't, 'Well I need to get the resources and hire a team and get the skills,'" Bruce said. "My answer was acknowledging that I couldn't compete with it, and so not competing with that, and then doing something completely different and out of left field, but still very good in and of itself."

The end result, Bruce said, is that Antichamber's art style "looks like it was made by someone who thought very deeply about what they were doing along a very different axis than the resources problem" when in fact, it was thinking exactly along that axis that inspired it. And despite the unconventional look of the game, Bruce reasoned it was ultimately more conservative than the alternative.

"That was always less risky to me because when you do things different but do them well, that's automatically something that people are interested in talking about," Bruce said. "But it's also less risky because I didn't have to invest $50,000 in trying to make good art to compete with what else is available and ultimately end up with a poor man's Call of Duty. It cost me nothing to make my art style."