The Psychology of The Uncanny Valley

It's a fine line between realistic and eerie - do video game characters live in or around the uncanny valley?

A few weeks ago my wife and I decided to fill in one corner of our geek credentials by checking out this Doctor Who show that everyone was going on about. We chose as our entry point the episode entitled Rose, which kicked off the show's 2005 relaunch. Unfortunately, about five minutes in my wife stood up, muttered "Nope, nope, nope" and walked out of the room. The reason? This was an episode where department store mannequins came to life, which she apparently found way too creepy.

"The uncanny valley is often cited as one reason why the cartoon robot Wall-E is appealing, yet Arnold Schwarzenegger's Terminator is not"

She's not alone, and the psychology behind her unease has several direct lessons for video game developers and artists - even more so now that upcoming consoles promise to make game characters more and more realistic. The 'uncanny valley' is an idea originally from the field of robotics, formalised in the 1970s by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori.

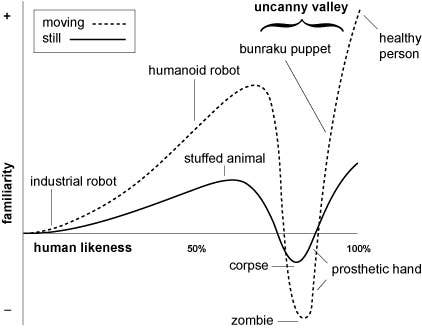

The gist is that if you plot people's comfort level with a robot you'd find that as you add more human-like characteristics, people are more likely to find it appealing - but only up to a point. The robot's likeability plummets when it gets a little too humanlike. Make the robot more and more humanlike and it eventually gets appealing again, but that dip in likeability is the eponymous 'uncanny valley' where the vocabulary people use to describe the thing starts to include words like "eerie," "weird," and "oh god it's looking right at me."

The idea has clawed its way out of robotics and into other fields. The uncanny valley is often cited, for example, as one reason why the cartoon robot Wall-E is appealing, yet Arnold Schwarzenegger's Terminator or the dead-eye CG characters in the Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within movie are not. And, of course, this all has applications in the design of characters in video games. It's often cited as one of the reasons why designers choose to go with more stylized aesthetics so that they can create appealing characters who rest comfortably to the left of the uncanny valley instead of spending tonnes of money and time in attempts to traverse it and scramble out the other side. Not everybody can pull off Nathan Drake from Uncharted, but characters like Sackboy from Little Big Planet or the robed traveller from Journey are a lot more practical and potentially more appealing.

The graph above is taken from the Wikipedia article on the uncanny valley and is based on Mori's work. The up/down axis represents how favorable our reaction is to an artificial creation, while the left/right axis represents how much it resembles a real human. At the far left are things like factory robots, and as you move along the right you get progressively more appealing creations like R2-D2 or Bender from Futurama. Add human-like qualities, though, and people start to dislike the creation at best and find it creepy at worst. Think zombies and the conductor character based on Tom Hanks in the animated movie The Polar Express.

But is the idea of the uncanny valley and the design lessons that artists take from it backed up by psychological science? Yes, turns out they are. Let's take a look at just two studies that speak to the design of character faces and body animation to see how.

First, Substantial research has shown that the mugs of human characters matter the most. We have evolved to pay special attention to the faces of other people as a way to do everything from empathise with them, communicate with them, and even look for signs of disease. So it shouldn't be surprising that faces are one of the most important things determining whether or not a video game character will live in the uncanny valley.

"When faces are more realistic, it doesn't take much tweaking to make them look creepy. When the faces are more stylized, a wider amount of facial distortion is acceptable"

One study by Karl MacDorman, Robert Green, Chin-Chang Ho, and Clinton Koch published in the journal of Computers in Human Behavior suggests this is true and provides some specific guidelines for those character creation tools we love to see in RPGs. In one of their studies, the researchers took a realistic 3D image of a human face based on an actual person. They then created eighteen versions of that face by adjusting texture photorealism (ranging from "photorealistic" to "line drawing") and level of detail (think number of polygons). Study participants were then shown the 18 faces and asked to adjust sliders for eye separation and face height until the face looked "the best."

The result? For more realistic faces with photorealistic textures and more polygons, participants pursued the "best" face by tweaking the eye separation and face height until they were pretty darn close to the actual, real face the images were based on. But for less realistic faces with lower polygons and less detailed textures, the ranges of acceptable eye separations and face heights were much larger. In a follow-up experiment the researchers did the same thing, except they asked the participants to adjust the sliders to produce "the most eerie" face instead of the best one. Again, when faces were more realistic looking, it didn't take much tweaking to make them look creepy, but when the faces were more stylized and less detailed, a wider amount of facial distortion was acceptable before things looked eerie.

But faces aren't all that matter. Other research suggests that the way a on-screen character moves also affects how uncanny we think it is. Or, more specifically, whether it moves how we expect it to. Researcher Ayse Pinar Saygin and her colleagues hypothesised that the uncanny valley effect might be because one of the things our brains have evolved to be really excellent at is making note of prediction errors - when something in our environment doesn't do what we expect it to.

Saygin and her colleagues tested this idea through a clever experiment with a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine and video clips of the famous-in-certain-circles "Repliee Q2" - a very realistic looking android from Japan that can easily be mistaken by a person at first glance.

The researchers hooked study participants up to the fMRI so that they could examine brain activity while looking at three video clips: an android with its exterior shell stripped away so that it was obviously a robot, the realistic looking Repliee Q2 android, and the actual human woman upon whom the android's appearance was based. They found that the "action perception system" in the brain - that is, the bits attuned to perceiving movement - were much more active when looking at the realistic android. A robot moving like a robot? No problem. A human looking all human-like? Not remarkable. But the bits of grey matter really got to work when something they thought would move like a human instead moved like something non-human. This, they argue, may be the neurobiological basis for the uncanny valley effect: a prediction error in how something ought to move.

So, what does this mean for game designers and artists? One clear implication is that there's only a small margin for error when you're trying to make something look like a real human on screen. Certain facial features may only be off by a very little bit before things look weird. So if you've got a game like Tiger Woods PGA Golf or Mass Effect that lets players customize an avatar, you may want to place some narrow boundaries on the "randomise" feature unless you want players grimacing and jamming on the "cancel" button. You may also want to test drive character faces and allow testers to tweak them to make them less weird.

Similarly, movement matters if you're trying to be realistic. Some games spend a lot of money to get this right and they really stand apart from others. It's not just about having characters doing human things like shifting their weight or changing poses. It's about having them do it really smoothly and realistically. Double for facial animations.

The flipside of all this, though, is that if you don't have the budget, expertise, or time to craft super high resolution skin textures or do motion capture, going with a more stylized art direction may keep your characters out of the uncanny valley. Dishonored comes to mind as a recent example, with its exaggerated character models that can get away with more because the game's design doesn't try to make them look too real. So artists and designers have choices. Not every game needs to shoot for super realistic, no matter what the hardware manufacturers' marketing folks claim is possible.

Jamie Madigan writes about the overlap between psychology and video games at www.psychologyofgames.com. Follow him on Twitter: @JamieMadigan.