Ending the Violent Game Debate

Devs behind Twisted Metal, Night Trap, Papo & Yo, and Huntsman: The Orphanage on whether there's a problem, and what can be done to quiet the critics

The violent video game debate is not new to America. Time and again, concerned parents and politicians from outside the gaming sphere have looked at the industry's most envelope-pushing efforts and worried about the effect they might be having on children playing them. It was Death Race that first sparked concerns in 1976; Doom and Mortal Kombat in the early '90s; and Grand Theft Auto and Manhunt in the oughts.

Any hope that last summer's US Supreme Court victory for the games industry would put an end to the issue once and for all went by the wayside last month, when a young man entered Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut and killed more than two dozen people, 20 of them children under the age of 8. With the issue back at the forefront of the public consciousness, GamesIndustry International sought insight from a handful of developers whose careers have been defined by violence, sometimes in quite literal ways.

Take Vander Caballero for example. The Minority Media creative director swung from designing the 2008 military shooter Army of Two to last year's Papo & Yo, in which players control a young boy coming to grips with his abusive father's alcoholism. In the former, players are the perpetrators of violence. In the latter, they are the victim of it. In both cases, Caballero's treatment of violence was informed by his own experiences growing up in the midst of the Colombian drug war.

"I saw a lot of violence in Colombia," Caballero explained. "There were guns in my home. My father had bodyguards, and they wore guns at home. It was quite disturbing to see that as a kid...So I saw the use of guns in context, for protection, for defense. On both sides, from the insurgent people who wanted a better life and from the people in a position of privilege trying to maintain that power and also defend themselves from criminals."

"I decided I couldn't do it anymore. It felt totally wrong for me to keep working on the type of entertainment where there was no moral behind what you were teaching to people."

Vander Caballero, on leaving AAA game development

Caballero tried to include that context in Army of Two, critiquing the military industrial complex through the events and dialogue of the game's campaign mode. But much to Caballero's disappointment, it was the game's context-free multiplayer mode that drew the most attention and acclaim from players. He compared the difference in experience to what one might see in a novelization of the board game Monopoly. While the board game itself might be good fun for a group of friends, it lacks context the novelization could provide as to the human cost and implications of engaging in ruthless business tactics with the goal of not just prospering, but actually bankrupting other people.

"I decided I couldn't do it anymore," Caballero said, explaining why he left the AAA industry to create games like Papo & Yo. "It felt totally wrong for me to keep working on the type of entertainment where there was no moral behind what you were teaching to people."

David Jaffe is less conflicted about his work. As a co-creator of Twisted Metal and director of the original God of War, Jaffe made a name for himself with games that are distinctly violent. But unlike Caballero, he seemed to view the altered context of violent games as almost reassuring, evidence that gamers aren't obsessed with gore for gore's sake.

"If you've played games, you know inherently, very quickly, that all of that stuff is what gets you in the door," Jaffe said. "It's the candy wrapper. It's not really why you're playing the game. It might be what entices you in the beginning, but very quickly you're focused on spatial relationship puzzles, risk-reward challenges, resource management, and meta-strategic choices. Your brain is engaged and you're looking at things not so much in context of, 'This is war.' You're looking at things in terms of, 'How do I survive the situation? What are the tools at my disposal?' And most people don't see that because they don't play these sorts of games and they just have the surface to go on."

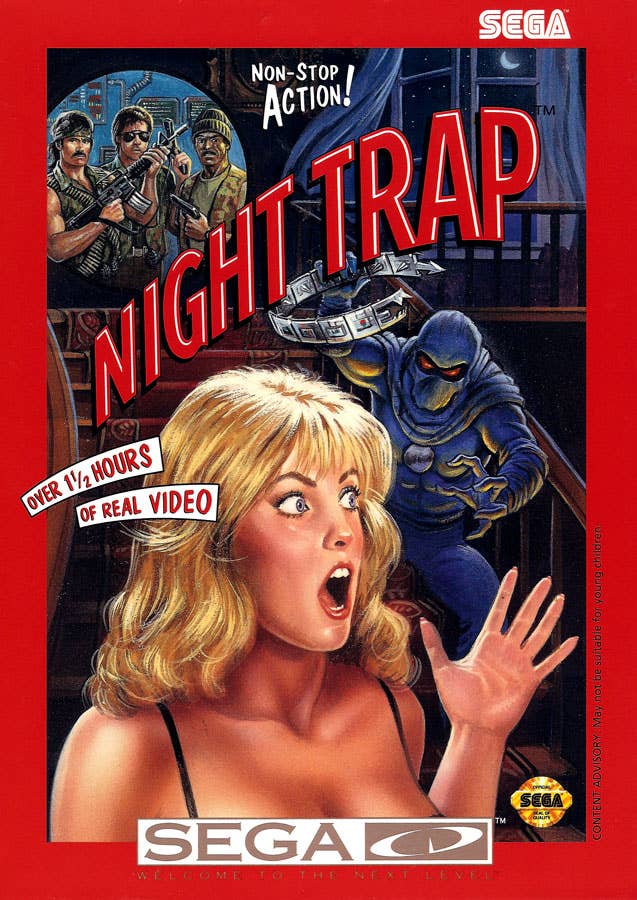

In comparison to the violent games Jaffe and Caballero have on their resumes, Rob Fulop's work is relatively tame. Even so, the co-designer of the early '90s full-motion video game Night Trap found his work at the heart of one of the earliest iterations of the violent game debate. Night Trap was one of a handful of games specifically scrutinized and criticized during Senator Joseph Lieberman's 1993 Congressional hearings on gaming violence. Fulop said the experience definitely changed how he felt, but not about violent games.

"I met Joe Lieberman and I realized that in his heart and his soul, he really doesn't care."

Rob Fulop

"The only change is that I learned more about the political system," Fulop said. "I met Joe Lieberman and I realized that in his heart and his soul, he really doesn't care. He just is using [violent game concern] as a platform because it's easy to get people on his side. The person who's standing up and screaming about this says, 'Hey there's an issue I can get behind and nobody can argue with me. No one can prove me wrong. I can sound like a good guy.'"

In Fulop's view, that makes gaming a perfect scapegoat for policy makers, because the industry's options to respond are few.

"The only defense really is free speech," Fulop said. "Nobody can argue skillfully that it's good for kids to have a game where you can run around killing everyone. But you can make the argument that you have the right to put that game out there."

There's even been discussion of late as to whether the best course of action for the game industry is to bother making that defense, or simply choosing silence as an alternative. Even the industry's recent meeting with US Vice President Joe Biden to discuss proposals to curb gun violence drew criticisms within the industry.

"If somebody said, 'Hey Jaffe, come meet with [US Vice President] Biden about this issue--not that they would--I'd have said thank you but no thank you," Jaffe explained. "Going and having that meeting, all it really did was cement the view of 'You guys are part of the problem' in the minds of people who already thought that...The fact that we're now sitting at the same table as the [National Rifle Association] as part of the problem? What a ******* disaster for public relations."

"The fact that we're now sitting at the same table as the NRA as part of the problem? What a ******* disaster for public relations."

David Jaffe

Taking the opposite view, Shadowshifters Entertainment director Dene Waring believes silence on the issue would be self-defeating. Waring is eager to talk about violence in games, even though he won't use it in his own. The developer described his upcoming debut game Huntsman: The Orphanage as an experiment in making a horror game without violence or blood.

"We need to talk about the subject of ultraviolent games," Waring said. "It needs to keep coming up because there's something that seems a little aberrant in that whole concept of glorifying psychotic, sociopathic behavior, glorifying the ultraviolence and expressing it so explicitly with the explosions of blood that occur when somebody's shot, and the levels of realism for what are becoming murder simulators. I do see that as a problem. I do see it as rather odd as a cultural phenomenon. Why take that aspect of human behavior, one of the most extreme and hopefully rare aspects of human behavior, and create simulators about that?"

While Waring was undecided on the effects violent games might have on players, he said developers should rethink their approach regardless.

"You would have to say apart from looking for scientifically provable links, is it really cool? Is it a good thing? Why do it? In my point of view, it just seems completely counterproductive to having a good world with people having a good life in it," Waring said.

"Why do it? In my point of view, it just seems completely counterproductive to having a good world with people having a good life in it."

Dene Waring, on making violent games

For some developers, concrete evidence would be a stronger incentive for toning down game violence than rhetorical questions. Jaffe said it was impossible to "child-protect the corners of life," but added that he would drop violence from his games if the data showed conclusively that his work was hurting society.

"Absolutely I would stop in a heartbeat," Jaffe said. "Nobody wants to be the cigarette companies."

One thing Jaffe and Waring agreed on was that the gun violence problem was multi-faceted. Jaffe chalked it up to the inherent nature of man, mental health issues (and the stigmas associated with them), and "too many ******* guns in the country." The gun culture in America was also a major concern for Waring, who saw it first-hand as a New Zealander visiting New York, in a toy store of all places.

"I watched an average-looking customer come in to return a faulty train set," Waring said, "and in a very short space of time, pull a gun and say, 'Tell me that you're f'ing with my rights. Go on, just say it. Say it. Just tell me you're f'ing with my rights.' Over a toy train refund. And to have stood there in that toy store and seen that culturally, even though this guy's obvious unhinged, he had a gun. And he felt that it was relevant and OK to pull it on a toy store sales clerk and threaten to take his life over such a trivial thing. It was his conflict resolution tool, and he felt fully justified and within his rights as an individual, and as a citizen of a country that backs him up."

It's not as if that was Waring's first exposure to guns. As with Caballero, Waring's attitude toward firearms was shaped in part by first-hand experiences with them (an incredible story which is a feature unto itself).

So what can the industry do to break the cycle, to end the gaming violence debate and avoid another reprisal of the issue should still more unthinkable tragedies become painfully real? Some are more resigned to history repeating itself than others.

"There will never be anything that can be done, I don't think. It will just always be there. I don't think there's a way to prove that violent media doesn't cause any harm in some people."

Rob Fulop, on quieting violent game criticism

"What if nothing can be done? There will always be politicians that will stand up and rally around this cause," said Fulop. "It will happen with higher resolutions and virtual reality. There will never be anything that can be done, I don't think. It will just always be there. I don't think there's a way to prove that violent media doesn't cause any harm in some people."

Caballero suggested the industry could stifle the issue in the long term by diversifying its output. The developer described what he called a sad state of affairs in gaming today, where no company is willing to fund a major game unless it has guns or some other form of violence in it.

"Right now the industry is such an easy target because the biggest sellers of games are about killing people," Caballero said. "Where are the other big games there to defend us? We don't have a Schindler's List in games. You can go attack the movies, and [the film industry] responds, 'Yeah, but those movies are violent movies, and there's this other broad spectrum of movies that offer a different perspective.' We don't have that in games. Games like Papo & Yo are rare."

Waring echoed that sentiment, noting that people can dismiss a B-grade slasher flick as exploitation cinema, but said people don't make the same distinctions when it comes to games. But before the industry's offerings can be properly expanded upon, he said the first step is a bit of honest self-assessment.

"The gaming industry as a whole has seemed to vulcanize in saying 'not us' and pointing the finger elsewhere," Waring said. "In fact, they should look at the most extreme examples. And let's ask the question of ourselves, and let's ask the question publicly: Have we gone too far at the extreme end? Should we be pulling back there, looking for other ways to provide the thrill factor so we can still hit the sales figures we want? Are there other buttons we can push without presenting the ultraviolence as the entertainment medium in itself?"

Jaffe's suggestions were less about changing the content of the games the industry is making, and more about celebrating the power of the medium and the work of its creators.

"It's so amazing how we've still done such a ****** job about showing off what makes our medium great."

David Jaffe

"What we should have been doing is saying some of this stuff is crass, some of this stuff is violent. Some of it has no real value, even on a pure entertainment level. Some of it, potentially a lot of people think is art. Art or not, though, a lot of people love it and it brings a lot of people joy," Jaffe said, adding, "The last thing the industry should do is try to whitewash itself and vanilla-ize itself when it is so varied and creative and thriving when it comes to imaginations working together to create cool stuff."

But it's not just about educating the outside world to the real value of gaming. That's something Jaffe says isn't always understood even by those firmly ensconced in the industry.

"The reaction I see from people when they ooh and aah when they see something violent is a normal human reaction," Jaffe said. "But it reminds me of the same reaction I see when people see amazing, jaw dropping next-gen graphics and they ooh and aah at that. And I'm sitting in the back screaming, 'Our medium is interactivity! Why don't you guys get vibed and jazzed about something like Minecraft?' It's so amazing how we've still done such a ****** job about showing off what makes our medium great."