Fat Pebble: Zynga, creative control and claymation

How a three-man studio secured a publishing deal with Facebook's biggest games publisher

There's no real way of avoiding it. Zynga isn't very popular.

I'm not talking audience figures - Zynga is still Facebook's biggest publisher, whether you slice it by daily or monthly average users, and the company has three titles in the top ten on the network. People still flock to almost anything suffixed by "Ville", albeit in smaller crowds than they once may have.

Nonetheless - there has to be a reason that there was so much gloating as stocks have plummeted and executives fled over the last few months. Perhaps it's resentment over the company's success, or defenders of the boxed console model crowing over the downturn of an upstart rival? Perhaps it's the accusations of copycatting, or Pincus' defence of it? Perhaps size just makes it an easy target.

I'll admit, I've always erred towards the suspicion that Zynga has been doing something untoward. Not illegally, or maliciously, but just somehow distasteful. Not quite wicked witch of the west, but with something of the pantomime villain about it.

So I'm surprised when Michael Movel of Brighton studio Fat Pebble tells me that they've been an absolute joy to work with - and even more so when I believe him.

Contrary to my expectations, Zynga hasn't meddled in the affairs of Fat Pebble or the studio's first game, ClayJam, at all. Total creative control has remained firmly in the hands of the developers, as has the all important ownership of the IP.

"They've been nothing but decent to us," Movel tells me as we huddle in the outfit's tiny studio, located in an attic above a creche. It's perhaps not a surprising response, given that the ink on the cheque is still pretty fresh, but it's clear that Movel, fellow programmer Iain Gilfeather and art lead Chris Roe, have already been through similar doubts about the potentially double-edge sword of a Zynga partnership.

"We were a bit nervous as well," Movel continues, "coming from console development where you have that publisher developer relationship... which isn't always so amicable."

"We did have conversations about it," Gilfeather interjects. "After Zynga had been in contact to say they were interested in publishing the game and we didn't know the details. We were left to think about it for a couple of days before we had to get back in touch with them to negotiate. We all definitely wanted to do it, but we did think about the downsides of it.

"One of the potential downsides was that the outside opinion of us might change. We had a list of our demands - it had to remain our IP, we wanted creative control, it had to still be our game - they were just publishing it. We were ready to fight for those, but that was what they were proposing as well."

"Speaking for myself, I didn't really mind that," Movel counters. "We'd been through the process and we knew it was really important to keep creative control so I thought as long as we kept that, I'd be happy. If anyone else disagrees, fine, but I'm willing to argue that this is still an independent game - we made it and Zynga came after that.

"Even if people strongly disagree with that, I'd fight our corner and tell them why I think this is still our game. So, I wasn't scared of that."

The deal might only be for one game so far, but Fat Pebble are one of the Zynga Partners for Mobile launch studios, sharing some prestigious company along the lines of Phosphor Games Studio's Horn, Crash Lab's Twist Pilot, Sava Transmedia's Rubber Tacos and Atari's Super Bunny Breakout.

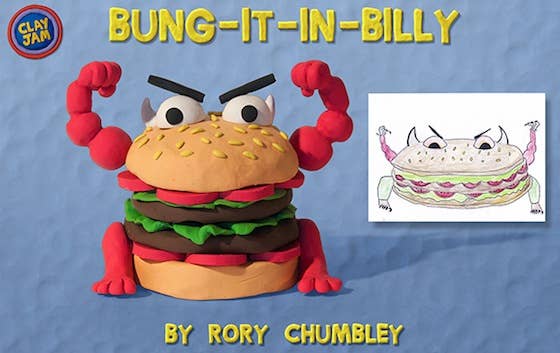

The game that clinched that deal is ClayJam, a riotously colourful and unashamedly childish game about rolling a pebble down a hill and collecting mass on the way to drive off the monsters who have taken up residence at the bottom. It's beautifully produced, quickly addictive and has a beautiful soundtrack. And it was all made from plasticine in a garage just down the road from the office.

"I did it about 2 minutes away, in my garage," Chris Roe tells me. "It was quite a mess in there for a while. I had to make sure that the set-up wasn't going to change, which is why I did it in there. It was full of junk but it didn't have a car in it, so I cleared enough space. I just used plasticine and normal clay modelling tools.

"That was just because I wanted to make a game using plasticine," Roe laughs, when I ask him where the idea came from. "I used to do it a lot when I was a kid - I made my own plasticine animations, before I got into any computer stuff. When I did get into computers I was always tempted to get away from them and do more hands on stuff."

"Claymation is quite a ridiculous idea to do if you're not geared up to do it"

Chris Roe - animator.

"You mentioned that you'd thought of the idea of a clay game before, at previous studios, when they'd had brainstorms" adds Iain. "A lot of studios do that. Black Rock did especially, try to involve everyone in that creative process. Which is great, but you're never really going to be in the creative decision making process when there's 100 of you in the studio."

"Claymation is quite a ridiculous idea to do if you're not geared up to do it," Roe points out. "If you've got a workforce that's doing specialist computers animation and stuff, to then switch to doing claymation is probably not going to go down too well. You can only really do it if you're a little outfit."

So, after a year of work in a garage with a DSLR, some halogen lamps, G-clamps and a lot of patience, ClayJam was born.

"We just wanted to make a game that we'd like, really," says Movel, chuckling. "It just so happened that it turned out to be a game for children. To start with we were thinking that maybe we'd actually use 3D models - to try and get that plasticine look with those, but it really quickly just became obvious that we'd need to actually use proper plasticine and claymation.

"We were planning on just doing it ourselves, learning from that and hoping to make the next game better, but we did a preview video. Zynga saw that, I guess they've got people looking for that sort of thing - and they got in touch with us.

"Originally they just said, we like the game, keep in touch with us, and then a bit later on we needed a bit more money to make ClayJam so we were asking around to see if anyone had any work for us. We asked Zynga and they said no, but we'd like to publish your game."

Going it alone on such an ambitious project would have been a daunting task, but Fat Pebble bomb-proofed itself by maintaining a healthy portfolio of contract work, ensuring that the company pocketbook stayed buoyant.

I ask if things could have ever gone terminally wrong, even with a back-up plan in place.

"We didn't plan to take a year, we were planning for it to take about three months - just do a little game made out of clay"

Michael Movel

"It could have done," says Movel, although I sense he doesn't really believe it. "That's one of the things we learned along the way. One of the biggest problems for us during this development is that we haven't had an 'end goal'. We've just been very 'organic', which is a very poncey word, but our ideas and goals have really evolved.

"We didn't plan to take a year, we were planning for it to take about three months - just do a little game made out of clay - then we had other ideas and we put those in, making it a bit longer. But that's been hard - the hardest thing. There have been points where we thought: this is never going to end. But that's also one of the reasons why we've been doing some contract work - we've been funding it ourselves."

Even now, with the world's biggest social developer backing him, Movel is still laudably cautious and grounded.

"We want to make sure that, even if this doesn't make any money, we can still carry on and do other things. So it's a danger, but it's a risk worth taking because we're not betting everything on it, we're not saying that if this fails we can't carry on as a company.

"There was always a back up plan. We all want to make our own games, so there was always the chance that one or all of us will get tired of doing contract work if this doesn't work out. But, we'd generally planned on not making any money from ClayJam, just getting it out. Especially when we were publishing it ourselves - we just wanted to learn and see if we could do better with the next game."

"We can only spend what we've got," Gilfeather counsels, not I suspect for the first time. "If we ran out of money we'd just stop working on ClayJam and work on something else until we were able to carry on."

So far, ClayJam is seeing most attention from "women and kids," although as Movel puts it: "that's just from the comments, that's not a scientific thing." I suggest that, with that audience, an IP which lends itself wonderfully to physical incarnations and a publisher keen to iterate on successful games, surely some merchandising should be on the cards?

Again, Fat Pebble exhibit ambition tempered by sensible restraint, discussing a rush of ideas (toys, slippers, an interactive children's book and a TV series) before moving back to bringing ClayJam up to their exacting standards of polish.

"When you're working on your game, our game, you're controlling where it's going... I wouldn't want to lose the chance to do that again"

Iain Gilfeather

"I think it'd be good if we carry on doing updates, and maybe a few similar, spin-off games," Movel tells me after we've talked about the possibility of Christmas jumpers. "But also, when we do a new game, have it completely different. I think that there's a lot of stuff that we'd like to do, we've got whole lists of new features that we'd like to get in and around Clay Jam, but I think definitely that if there's another game then it'll be whatever suits that game."

Has the big league partnership and the flush of potential success led to thoughts of acquisition? Will the team abandon its indie principles for the right package?

"We have certain requirements," says Movel, steepling his fingers in mock villainy. "If we meet those requirements we're open to anything. We're not that sort of indie who's opposed to making money, we like to make money, but we also want to keep creative control. If anyone came to us and met those requirements we'd be willing to discuss it with them."

"Doing this was a massive amount of fun," adds Iain. "It was incomparably rewarding compared to working on someone else's game. When you're working on your game, our game, you're controlling where it's going... I wouldn't want to lose the chance to do that again."